Who will pay for forcing the Campbell Coal plant to stay open?

Key Findings

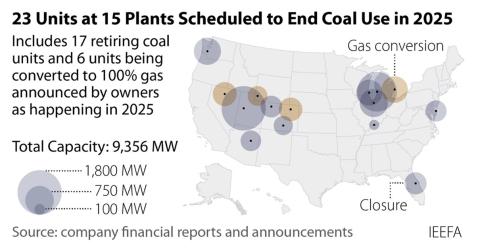

The U.S. Department of Energy has ordered a Michigan-based utility to keep a coal plant open just days before its scheduled closure.

Consumers Energy has been working in cooperation with state and regional officials to close the aging coal plant since 2021.

If the plant is forced to stay open, ratepayers will be stuck with the costs of finding new staffing, new sources of coal, and squeezing out of cheaper renewable sources.

The contrast between the long-term planning and the sudden federal order could not be starker. Consumers should be allowed to shutter the plant.

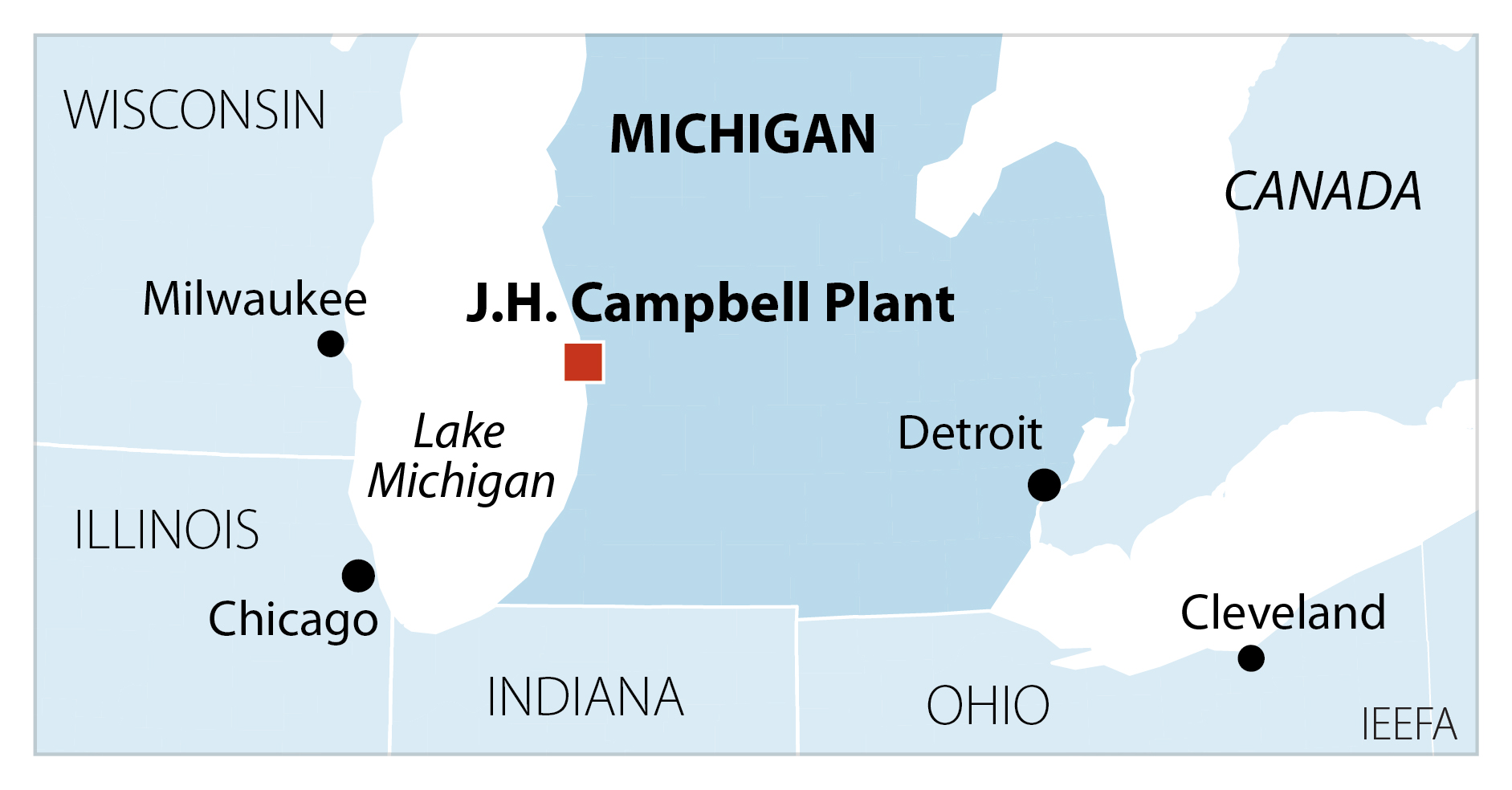

The administration moved forward with a controversial market intervention last month, ordering the aging J.H. Campbell coal-fired power plant in Michigan to remain open through the summer. The plant had been slated for retirement on May 31, and the unprecedented move, relying on the administration’s previous declaration of an energy emergency, raises a host of questions about the operation of U.S. power markets, including who will pay the sizable cost of keeping it open.

The facility, the last coal plant owned by Michigan-based Consumers Energy, includes three units and has a total summer generating capacity of 1,401 megawatts (MW). Two of the units are old by coal plant standards: The 260MW Unit 1 came online in 1962 and the 356MW Unit 2 came online in 1967, both well past the average retirement age of 50 for U.S. coal plants since 2000. Unit 3, 785MW, came online in 1980.

Consumers Energy announced its plan to retire the coal facility in 2021, and MISO, the regional grid operator, approved that plan three years ago, in March 2022. MISO operates the electricity market and power grid for a 15-state region in the central U.S. that runs from Louisiana north to Minnesota and into the Canadian province of Manitoba.

Plant closures and adding new generation are not decisions that are made arbitrarily. The utility worked extensively with both the Michigan Public Service Commission and MISO to get the approvals needed to replace the power capacity of the aging generators and ensure the closure of Campbell did not affect grid reliability. As part of that effort, Consumers has brought online 502MW of wind generation since 2020, bought the 1,055MW Covert combined cycle gas plant in 2023, and is in the process of adding 515MW of solar generation to its system by 2027.

These capacity replacement moves were clearly enough for MISO. The system operator’s endorsement is critical, since it has the authority to require plants to continue operating if it believes grid stability or shortages could occur. And MISO has not been afraid to act: In 2022, it required Missouri-based Ameren to keep its 1,195MW Rush Island coal plant open for reliability reasons. The decision was upheld by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the plant remained open for two additional years. MISO found no similar problems with Consumers’ plan to close the Campbell plant, saying as recently as May 8 that the region has sufficient resources to meet projected demand this summer. Despite this, the Department of Energy said in its May 24 emergency order that it was directing MISO and Consumers to keep the plant open due to an expected “insufficiency of dispatchable capacity” during the summer.

The contrast between the long-term planning by Consumers, Michigan regulators and MISO to close the plant while maintaining reliable regional power supplies and the sudden federal order to keep the plant open could not be starker.

Then there is the issue of who will pay for keeping the Campbell plant open. The order says nothing about who will end up footing the bill, but Michigan ratepayers almost certainly will be forced to pay for these costs, which will total millions of dollars. For example, in a case in West Virginia in 2023, the utility First Energy told regulators that it would cost at least $3 million a month simply to keep the Pleasants coal plant, a smaller and newer facility, open and capable of operating—and that was without the costs of actually generating power.

And generating power at the Campbell plant is likely to be costly for ratepayers. Units 1 and 2, which are 63 and 58 years old, respectively, were already increasingly uncompetitive in the MISO market, meaning it cost more to generate electricity than what it could be sold for. According to data filed by Consumers at FERC, the operation and maintenance costs for the two plants totaled $45.80 per megawatt-hour (MWh) in 2023 (the most recent data available). That puts both units in the red almost all the time in MISO: S&P data shows that the monthly around-the-clock price at the Michigan hub has been above $40/MWh just twice in the past two years, and never during the summer. In other words, the plant would lose money on virtually every MWh generated if past prices hold this summer, costs that could add up to many more millions of dollars if the units at Campbell are run for any substantial amount of time.

And there are other costs to consider, such as securing the coal supplies needed to operate the plant. With permanent closure just days away and the plant’s coal contracts set to expire, Consumers would have been trying to burn up the very last of its remaining coal stockpile. Without coal or contracts, the company could be facing some significant and potentially expensive challenges in resupplying the plant, given the volume of coal it had been using and the lead times usually associated with coal deliveries. These include possibly paying a higher price for coal without a contract, and paying the railroads for coal trains and delivery schedules on short notice to bring the fuel to the plant.

In 2024, Campbell burned more than 3.7 million tons of coal, all of it delivered by rail from the Powder River Basin (PRB) in northern Wyoming. That is an average of 12,700 tons of coal a day — roughly equivalent to a one-mile-long coal unit train a day, a substantial amount. Two of the PRB’s biggest mines provided that coal: Arch Resources’ Black Thunder Mine, which delivered 2.25 million tons, and Peabody Energy’s North Antelope Rochelle Mine, which delivered 1.47 million tons. For Arch Resources, the loss of the Campbell plant as a customer is significant since it accounted for more than 5 percent of the mine’s total output in 2024.

Additionally, any coal it does buy will have to be burned up by the new closure date in August, even if the utility loses money in the process.

The DOE order also says nothing about the operational challenges associated with running the aging plant, particularly Unit 1, which was not designed to ramp its power output up and down on a regular basis. An IEEFA analysis shows that Unit 1essentially ran at full power in 2024; if it operates in a similar fashion this summer, it will almost certainly force cheaper sources of power out of the market and raise power prices for Consumers’ ratepayers.

These cost concerns were stressed by Michigan PUC Commissioner Dan Scripps: “The unnecessary recent order from the U.S. Department of Energy will increase the cost of power for homes and businesses in Michigan and across the Midwest.”

Finally, there is the question of staffing. Utilities have a solid history of reassigning workers from retiring units to other facilities within their systems; other long-time workers may have planned their retirements. Given the lateness of the DOE order, those reassignments probably have been made at the Campbell plant as well, raising the question of whether Consumers will have the staffing needed to operate Campbell safely and reliably this summer, and what it will cost to do so.

DOE’s intervention In the MISO power was clearly unwarranted. MISO and Consumers have planned carefully for Campbell’s closure and the administration should not be trying to undo those decisions. If the order stands, Consumers and Michigan regulators should submit the bill for keeping the plant open to DOE; the utility’s ratepayers should not be on the hook for this unjustified, costly action.