Don’t rush to raise fixed network charges

Download PDF

Key Findings

Some stakeholders have proposed moving away from consumption-based network tariffs towards network tariffs with a higher fixed component.

Increasing fixed network tariffs could penalise households that use less energy from the grid, such as many low-income households, and those with energy efficiency upgrades, rooftop solar and storage.

In IEEFA’s view, tariff signals that maintain or strengthen signals for energy efficiency and peak demand reductions would be more effective in containing network and wholesale costs.

A first-principles review of the economic regulation of electricity networks should be undertaken to ensure fair cost, risk and benefit allocation across all stakeholders.

As households’ uptake of solar and battery storage grows and their use of electricity from the grid declines, questions have arisen about how electricity networks might fairly recover their costs. Some have proposed that rather than recover most of these costs based on power consumption, we should instead increase the fixed daily network charge, such that households would pay similar amounts for the network irrespective of how much energy they consume from the grid.

However, this approach could weaken incentives for energy efficiency and peak demand reduction. In IEEFA’s view, tariff structures should instead be designed to maintain or strengthen these incentives to ease upward pressure on network costs. First of all, however, we should undertake a first-principles review of electricity network economic regulation to ensure costs, risks, and benefits associated with network services are sized and allocated appropriately across all stakeholders. With that in place, the appropriate network tariffs are likely to follow.

Households’ use of the grid is changing

Australian households have invested enthusiastically in solar. They now look set to do the same with battery storage. This has reduced their reliance on the electricity network at certain times of the day and year. IEEFA analysis found that during January months, an 8-kilowatt (kW) solar system and 10 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of storage eliminates a typical household’s average daily peak demand in all cities analysed, while leaving spare capacity for export. Take-up of larger 20-25kWh batteries, which are increasingly common, could unlock even greater export potential.

Figure 1: Impact of rooftop solar and batteries on average January peak demand

Source: IEEFA.

Note: Figure shows impact of rooftop solar and batteries on peak demand for an average January day in each capital city, for households that have already upgraded to efficient electric appliances.

Electricity networks are built to cater for periods of high demand – generally hot summer days with high air-conditioner load. Given that solar and batteries typically provide significant energy on summer days, this has the potential to reduce network build requirements and expenditure. The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) found in its 2024 residential electricity price trends report that “the effective use of CER [consumer energy resources] can lower system costs for all households by reducing the need for additional network investment to meet peak demand, and reducing the risk of spikes in wholesale prices.” Modelling by Baringa also found that efficiently integrated distributed energy resources could deliver $11 billion in avoided network costs by 2040.

Electrification is also changing how customers interact with the grid. Electricity demand for electric vehicle (EV) charging will likely be large, and the timing around when new EVs draw power from the network will be crucial. If they charge during peak periods, this could necessitate costly network augmentation. However, if they are encouraged to charge outside peaks, or export back to the grid through vehicle-to-grid (V2G) during peaks, this could put downward pressure on network costs.

Even in times when a given household’s excess solar generation is low, such as in southern states in wintertime, home batteries or EVs with V2G could be programmed to draw power from the grid outside network peaks (such as in the middle of the day) and reduce the household’s peak demand (typically in the evening). Many homes will even have the capacity to export excess energy at those peak times. However, they need market signals to encourage this – which are largely missing today.

Network expenditure is set to rise, putting upward pressure on bills

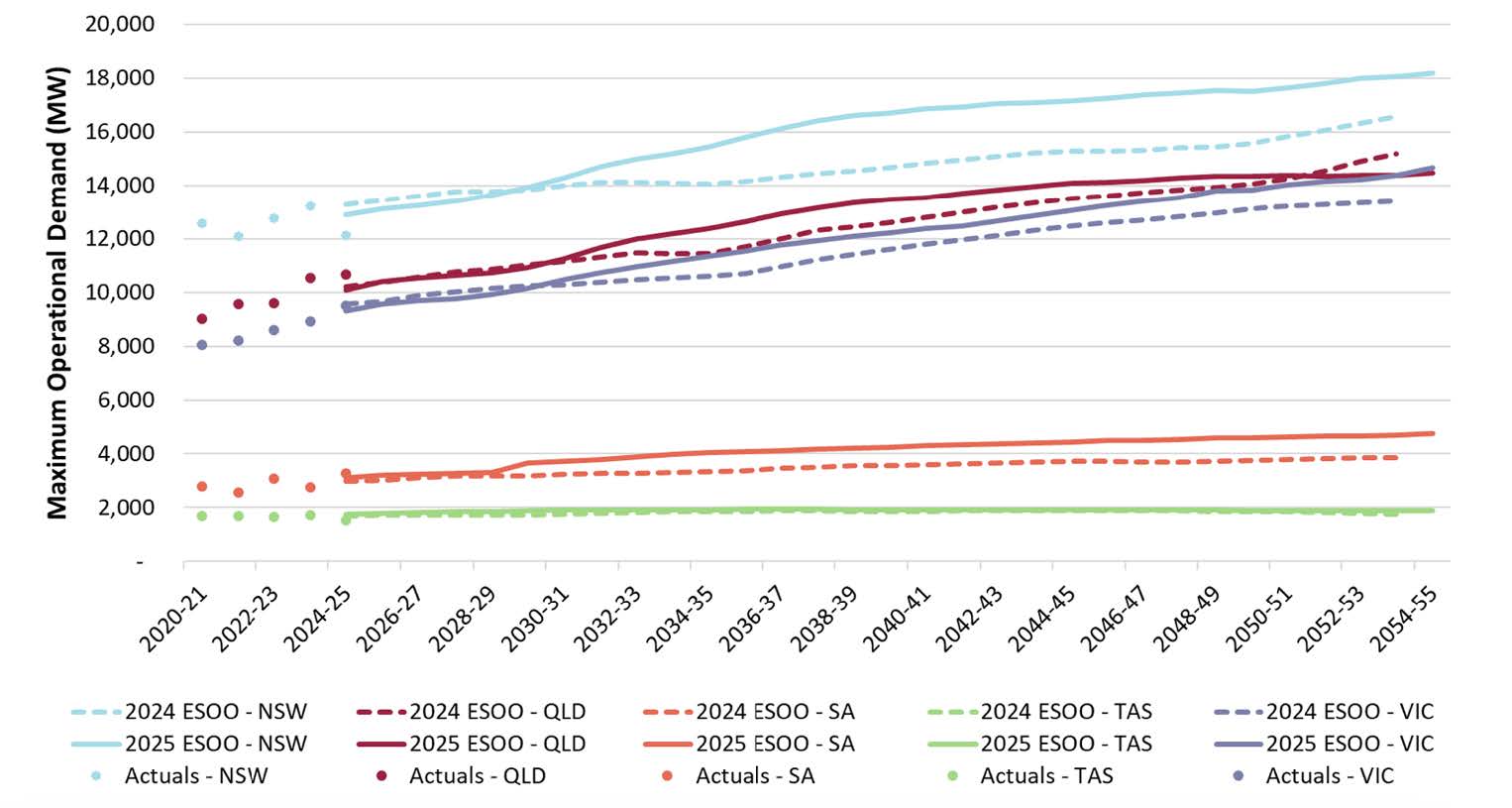

There is currently upward pressure on network expenditure. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has forecast steady growth in peak demand across a number of states – driven by factors ranging from large industrial loads to data centres to electrification and EVs. Victoria is projected to transition to a winter-peaking region by around 2040-41.

Figure 2: Actual and forecast maximum operational demand across National Electricity Market (NEM) regions, 2020-2055, megawatts (MW)

Source: AEMO; 2025 Electricity Statement of Opportunities (ESOO); Page 34.

Figures shown are regional annual 50% POE maximum operational demand (sent-out)

According to the Australian Energy Regulator (AER), combined (distribution and transmission) capital expenditure for electricity networks across the NEM increased by 19.7% in real terms in 2023. That year saw the highest electricity network expenditure since 2016 (though still below 2012 peaks). The increase in capex “was primarily driven by overspends of capital allowances by NSW electricity distribution networks, Ergon Energy and expenditure on project EnergyConnect being reprofiled to 2023”.

According to the AER, “electricity customers are facing a ‘wall of capex’ from distributors” for the next regulatory period of 2025-30, with some capex proposals by distribution network service providers at least 20% higher than the prior regulatory period. This spend includes costs for augmenting the network, connecting new customers, replacing old assets, upgrading systems and other costs.

The costs of building new network assets, plus the return on capital (which covers both returns for equity investors and the cost of debt financing), are recovered by network businesses via regulated network tariffs over the assets’ economic life, which can range from 35 years even up to 70 years. Higher network capex today can mean higher network tariffs for many years. Avoiding unnecessary investment can help limit bill increases.

Tariffs should reward consumer behaviour that eases upward pressure on network costs

Solar and battery storage profoundly change the way some customers interact with electricity networks. When households are able to serve their energy demand with their own onsite generation only, they are not relying on the grid for imports. In those periods they therefore avoid paying consumption-based charges, which include a portion of network costs.

This has led to a concern over cost shifts, whereby households with solar-battery systems could pay for a smaller portion of network costs than those without them. Recently there has been a push towards moving a higher portion of network costs into the fixed daily portion of the charge to address this, from stakeholders such as the NEM Review Panel in its recent draft report. However, this approach has a number of likely drawbacks:

- It penalises lower-consuming households, such as many low-income households and households who use energy more efficiently.

- It reduces the signal for peak demand reductions, which could hamper our ability to avoid the “wall of capex”, and to drive network cost reductions.

- It reduces the signal for investment in rooftop solar, storage and energy efficiency upgrades, which are important technologies to support meeting emissions reduction targets and easing peak demand, and compromises consumers who have already invested expecting a given return.

The NEM Review Panel has also suggested that customers in aggregation services (for example a household with a battery enrolled in a virtual power plant (VPP)) should be offered “dynamic (cost reflective) network tariffs”. However, this would only apply to a portion of customers so the signals provided through those tariffs would not be far-reaching.

We face a pressing question regarding tariffs, given the AEMC Electricity Pricing Review currently underway. Should households and businesses be incentivised to a greater extent to improve their energy efficiency and lower their peak draw from the grid, particularly as electrification and automation of energy assets ramps up? Or should that signal be dampened by moving a higher portion of network costs into a fixed charge?

In IEEFA’s view, customers should be encouraged to reduce their peak grid demand and to use energy more efficiently – as this can ease pressure on both network costs and wholesale costs.

Network tariffs that support peak demand reductions and energy efficiency could alleviate network augmentation requirements, helping to avoid the “wall of capex”. Network tariffs are generally passed through to retail tariffs, so have significant implications.

There is an argument that customers can’t or won’t always respond to tariff signals. This may be the case when the customer’s ability to adjust their energy consumption is not automated and relies on the customer consciously and actively changing their behaviour in given instances. However, new energy assets like batteries and EVs can increasingly be automated via software. Software systems can be linked in with appropriate tariffs to operate in ways that support the grid. Of course, customers who are unable to take advantage of such signals or are not interested in doing so should be allowed continued access to more standard tariff offerings like a flat rate.

It should also be noted that it isn’t necessarily the end customer that needs to grapple with this. Electricity retailers (or other intermediaries like Catch Power) can provide the services and software to help manage customers’ load on the network with the customer paying a simple fee in return (Reposit is an example of this with its ‘No Bill’ offering).

Moving to a higher portion of fixed network charges appears to go in the opposite direction of where we need to go to contain costs, reduce emissions and ensure an equitable energy transition.

We need a first-principles review of network economic regulation

While tariffs are undoubtedly important, we are currently facing deeper questions that go to the underlying fundamentals of electricity networks – rather than the by-product, network tariffs.

How should the costs, risks and benefits of the power networks be allocated between customer segments (for example, those with or without solar-battery systems; or residential versus commercial), generators and the network businesses? Should households and businesses who reduce their load on the network at certain times benefit from that, and what should that benefit be? Also, shouldn’t those who generate power closest to customers receive some advantage over those generators that require hundreds of kilometres of power lines to deliver their power?

In IEEFA’s view, we need to reform the economic regulation of electricity networks. A first-principles review should be undertaken to understand the full picture, and determine how to allocate costs, risks and benefits between stakeholders as well as the potential for solar, batteries and demand management to compete against networks. The review should analyse the benefit provided by households and businesses who reduce their load on the network at given times.

Once the review has been undertaken and the resulting reforms have been made, the most suitable network tariffs are more likely to follow.

This commentary was originally published in RenewEconomy.