Europe’s CBAM raises supply chain carbon risks for South Korean technology industries

Key Findings

The European Union (EU) began imposing Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) tariffs from 1 January 2026, taxing imports based on embedded carbon emissions. Currently, CBAM is levied on high-carbon commodities, with scope expansion under consideration.

The implementation of CBAM-similar mechanisms in non-EU countries could increase production cost volatility and product prices, undermining South Korea’s export competitiveness.

The potential inclusion of semiconductors and liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the EU CBAM could materially impact South Korea’s technology industries, with CBAM certificate costs estimated to reach USD588 million between 2026 and 2034 under a high EU ETS price scenario.

Rising carbon-related costs across South Korea’s LNG-based semiconductor and fossil-fuel-powered Artificial Intelligence (AI) data center supply chains could heighten counterparty risk and production expenses, prompting buyers to shift from high-emission suppliers to lower-carbon alternatives.

The European Commission began imposing tariffs under its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), the world’s first tax on carbon intensity of imports, from 1 January 2026. This followed a provisional reporting-only period from 2023 through 2025, which allowed importers to adjust to the policy. The European Union’s (EU) CBAM, proposed in 2021, aims to prevent ‘carbon leakage’ by taxing imports entering Europe based on their embedded carbon emissions.

CBAM is levied on a set of high-carbon sectors, including iron, steel, aluminum, cement, hydrogen, electricity, and fertilizer. After an initial implementation period, the EU is considering expanding the list of imports subject to CBAM.

Under the mechanism, EU importers of more than 50 tonnes of regulated products annually must purchase CBAM certificates according to a formula that uses the carbon intensity difference between the exporting country and the EU, as well as differences between the values of the EU emissions trading system (ETS) and the origin country’s domestic ETS.

CBAM is calculated using a formula that reflects both the commodity-specific emissions intensity and the difference in carbon pricing between the exporting country’s carbon market and EU benchmarks, which are based on the EU ETS, the world’s most comprehensive and liquid carbon market.

CBAM adjustment = [(EFdirect + EFindirect)export market – (EFEU x Market phase-in factoryear(2026-2034))] x (Carbon Price EU ETS – Carbon Price Export Market ETS) Note: Direct emissions (Scope 1) reflect the carbon intensity of a manufacturer’s operations, and indirect emissions (Scope 2) reflect the carbon intensity of input or services the manufacturer purchases. The EU’s emissions factor accounts for the average carbon dioxide (CO2) per tonne for commodities produced in the EU. The market phase-in factor reduces the EU emissions factor, reflecting that EU producers are currently granted a certain amount of free emission allowances. Over the next few years, these allowances will be removed, resulting in CBAM costs increasing substantially for importers. |

EU CBAM raises supply chain carbon risks for South Korea

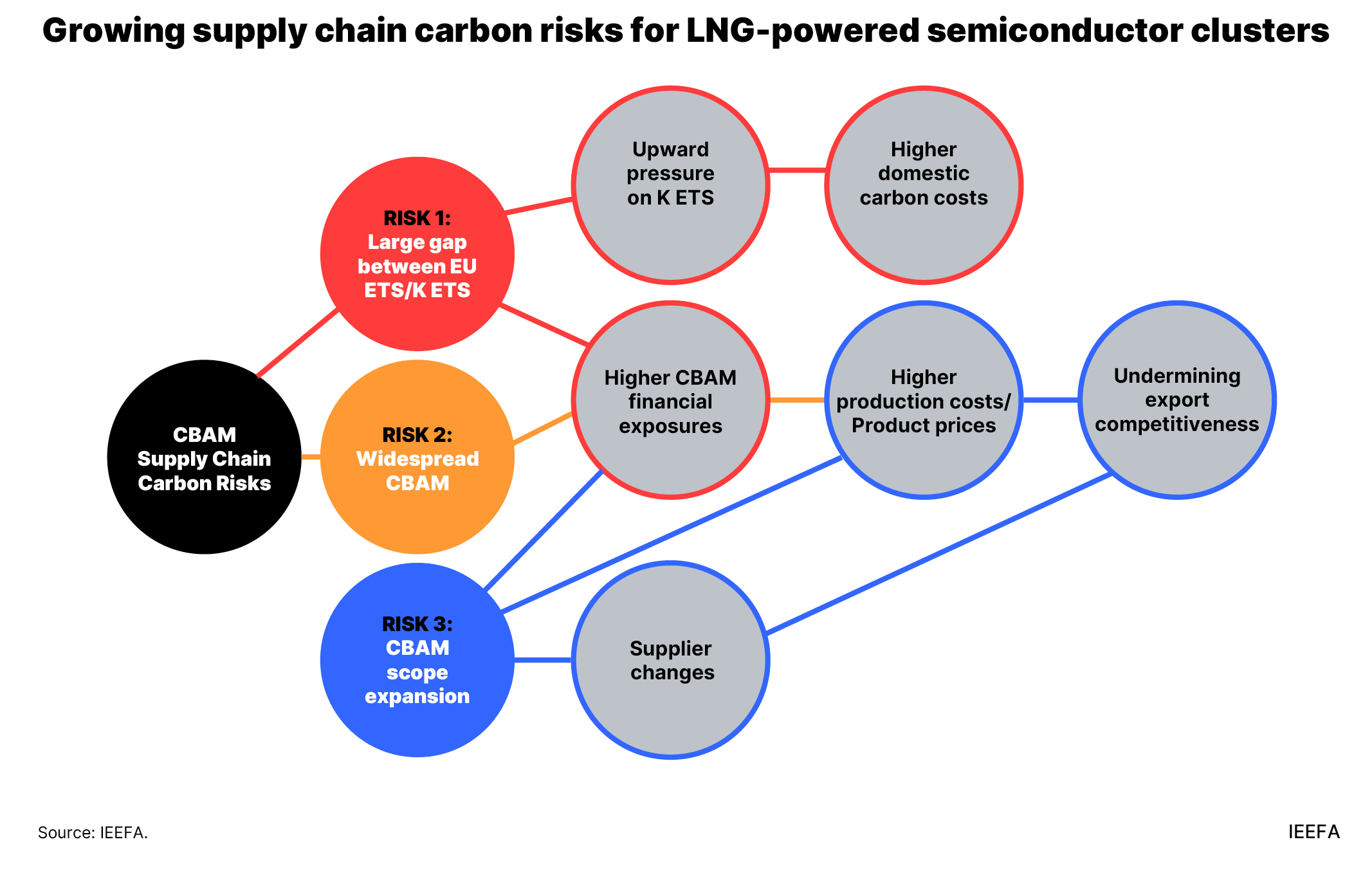

The full implementation of the EU CBAM has heightened supply chain carbon risks across three dimensions for South Korean industries with high carbon intensity.

First, a larger gap in carbon pricing between exporting countries and the EU could result in higher CBAM costs, driving a switch of suppliers to other countries with a narrower gap with the EU ETS to avoid high CBAM certificate expenses. As of 2025, the price gap between the EU ETS and South Korea’s ETS (USD6.45 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent [tCO2e]) is approximately USD63.92/tCO2e. According to the World Bank, this differential is significantly higher than that for China (USD58.61/tCO2e), Germany (USD21.82/tCO2e), the United Kingdom (USD13.14/tCO2e), and Switzerland (USD5.62/tCO2e).

Second, the widespread adoption of domestic CBAMs by non-EU countries could result in volatile production costs and ultimately increase product prices, undermining South Korea’s market competitiveness, given that exports account for 70% of its gross domestic product (GDP). As others adopt similar mechanisms, global carbon pricing could converge, potentially putting upward pressure on South Korea’s relatively low ETS.

The United Kingdom (UK) will implement its CBAM from January 2027 for imports of aluminum, cement, fertilizer, hydrogen, and metals that exceed GBP50,000 annually. The UK CBAM requires reporting direct and indirect emissions, making it more stringent than the EU mechanism, which has that criteria for cement and fertilizer only. Canada and Australia are also considering their own CBAM implementation.

Third, the potential inclusion of semiconductors and liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the EU CBAM scope could be a major setback for South Korean technology industries, which rely heavily on fossil fuel-based energy. While semiconductors and LNG are currently exempt from the CBAM, the energy-intensive nature of their production raises concerns, especially for South Korea’s planned semiconductor clusters that are expected to be powered by LNG. The European Commission initiated a public consultation in July 2025 and discussed extending the scope of its CBAM. This revision is likely to continue regularly. On 17 December 2025, the Commission announced the full implementation of the EU CBAM, as well as extending coverage to downstream products and strengthening anti-circumvention measures beyond the primary goods initially included.

The EU is the third-largest export destination for South Korea, accounting for approximately 10% of the country’s total exports each year. Should the EU impose the CBAM on semiconductors entering Europe, it could undermine South Korean companies’ market share. EU chip customers may decide to switch suppliers from South Korean semiconductor companies powered by LNG, which has a higher carbon footprint, to others that use low-carbon electricity. Additionally, production expenses could further increase if the EU CBAM’s carbon costs are factored into LNG-fired power procurement, as this would result in a substantial recalibration of LNG prices in international markets.

CBAM costs projected to impact 10% of total exports

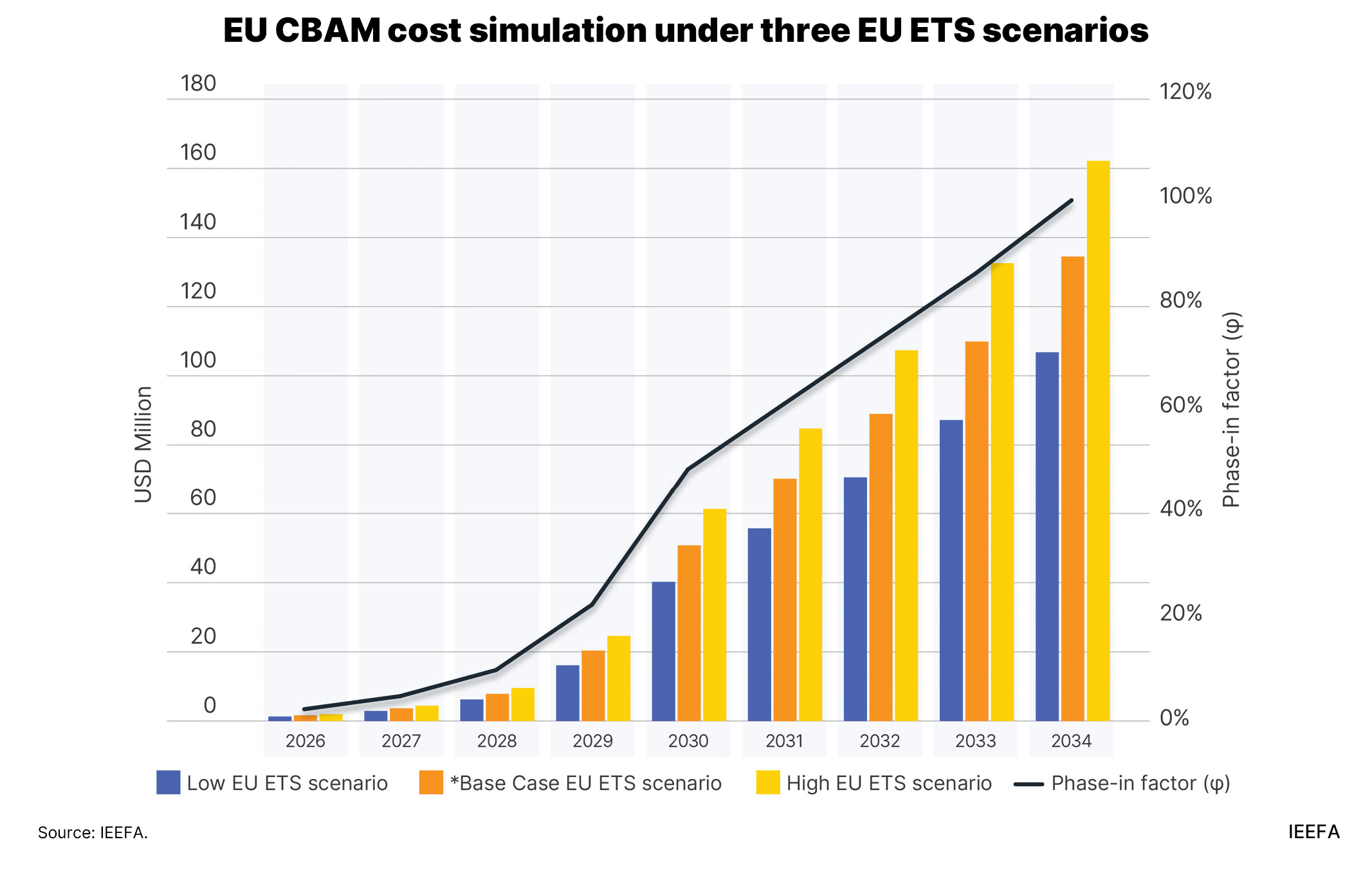

According to a scenario-based case study by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), up to USD162 million (approximately KRW233 billion) of CBAM certificate expenses could be incurred by South Korean chip exporters in 2034 under a high EU ETS, which accounts for about 9.9% of total chip exports to the region. IEEFA estimated that the total EU CBAM certificate expenses could reach approximately USD588 million (KRW847 billion) between 2026 and 2034 under the high-EU ETS scenario.

IEEFA’s analysis assumed that the semiconductor industry was included in the EU CBAM’s scope. The study estimates the CBAM certificate cost using an embedded emission factor (EEF) that accounts for the entire supply chain (Scope 1–3). The embedded carbon intensity was based on value rather than mass, factoring in annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and revenues to determine the value-based EEF. Since lightweight semiconductor chips could reduce CBAM certificate costs compared with heavyweight products, IEEFA assumes that the certificate cost calculations were based on value rather than mass.

Rising CBAM certificate costs impact market competitiveness

A sharp increase in CBAM costs on South Korean semiconductor imports could prompt European buyers to shift away from high-emission suppliers toward lower-carbon alternatives to reduce exposure. Although the IEEFA case study was based on 2024 exports, CBAM liabilities are likely to rise materially as LNG-powered mega-scale semiconductor clusters in Yongin begin operations from 2027, increasing the embedded carbon intensity of exported chips.

If CBAM coverage is expanded to include LNG and indirect emissions, Scope 2 emissions and electricity procurement costs would rise sharply, further inflating carbon expenses. The introduction of similar CBAM regimes in other jurisdictions, such as the UK, would compound these costs and erode South Korea’s export competitiveness. Rising carbon-related costs across LNG-based semiconductor and fossil fuel-powered Artificial Intelligence (AI) data center supply chains could heighten counterparty risk and production expenses, particularly as competing markets accelerate their transition to low-carbon energy systems.

South Korea should proactively address supply chain carbon risks to maintain the competitiveness of its semiconductor sector and emerging AI data centers.