Drumbeat of coal plant closures to continue in 2025

Key Findings

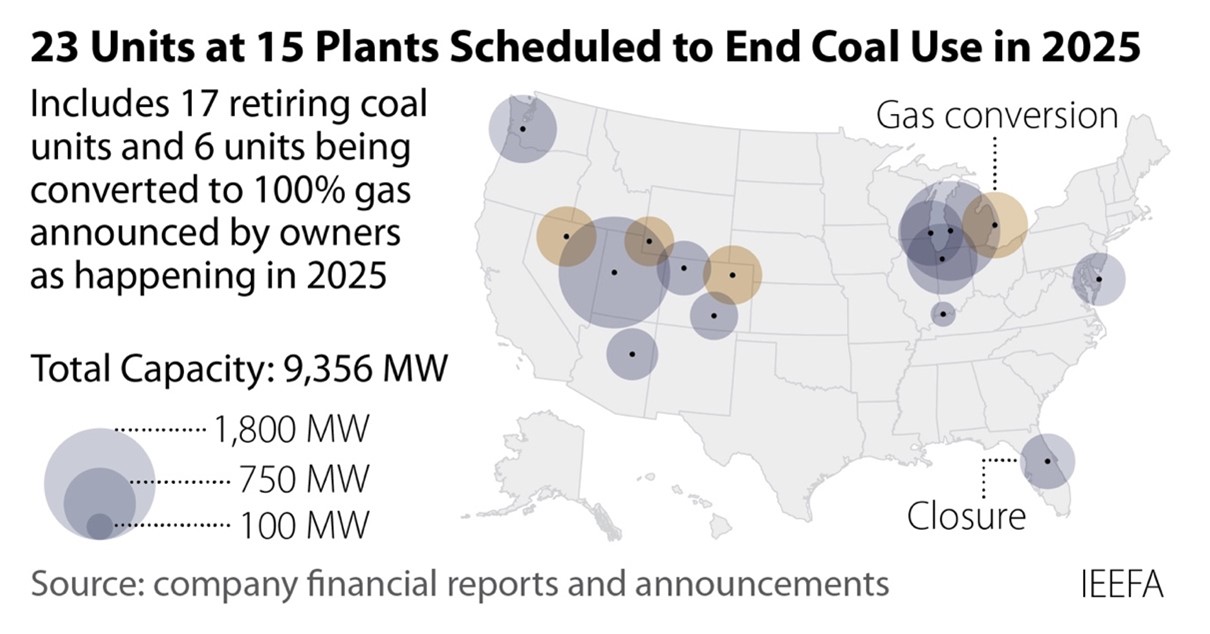

U.S. power companies have announced the closure or gas conversion of 9,356 MW of coal-fired capacity in 2025.

These closures, driven by economics, are part of long-term company plans crafted with significant state oversight and are in line with a remarkably steady and consistent trend away from coal.

Federal policy seeks to overrule the companies’ and state process to prevent coal plant closures, a legally questionable effort that would drive up electric bills without improving system reliability.

Rising costs for coal power, together with long-term investments in new generation resources and involvement by state regulators to ensure reliable power and reasonable rates are all providing momentum for the shift away from coal.

Short build times, flexible scale, and greater certainty of fuel costs continue to accelerate the construction of solar facilities and dispatchable battery storage, signaling coal’s limited future.

In February, when NRG Energy closed its last coal-fired unit at the Indian River power plant in southern Delaware, it marked just the first of 23 coal-fired units at 15 power plants that were expected to stop burning coal in 2025. These closures, announced by the companies that own them, total 9,356 MW of capacity, and include 17 units in nine states being retired, and six units in four states that are converting to run on 100% gas. The power companies making these changes have been planning them for years; have approval or are awaiting approval from state regulators; have invested millions of dollars in replacement generation facilities; and have worked to ensure the reliability and level of power needed by their customers remains uninterrupted. Now, however, the administration, in support of the coal industry, is seeking to overrule this state and company decision-making process to prevent these closures. This legally questionable effort, if successful, would cost utility ratepayers dearly without improving system reliability.

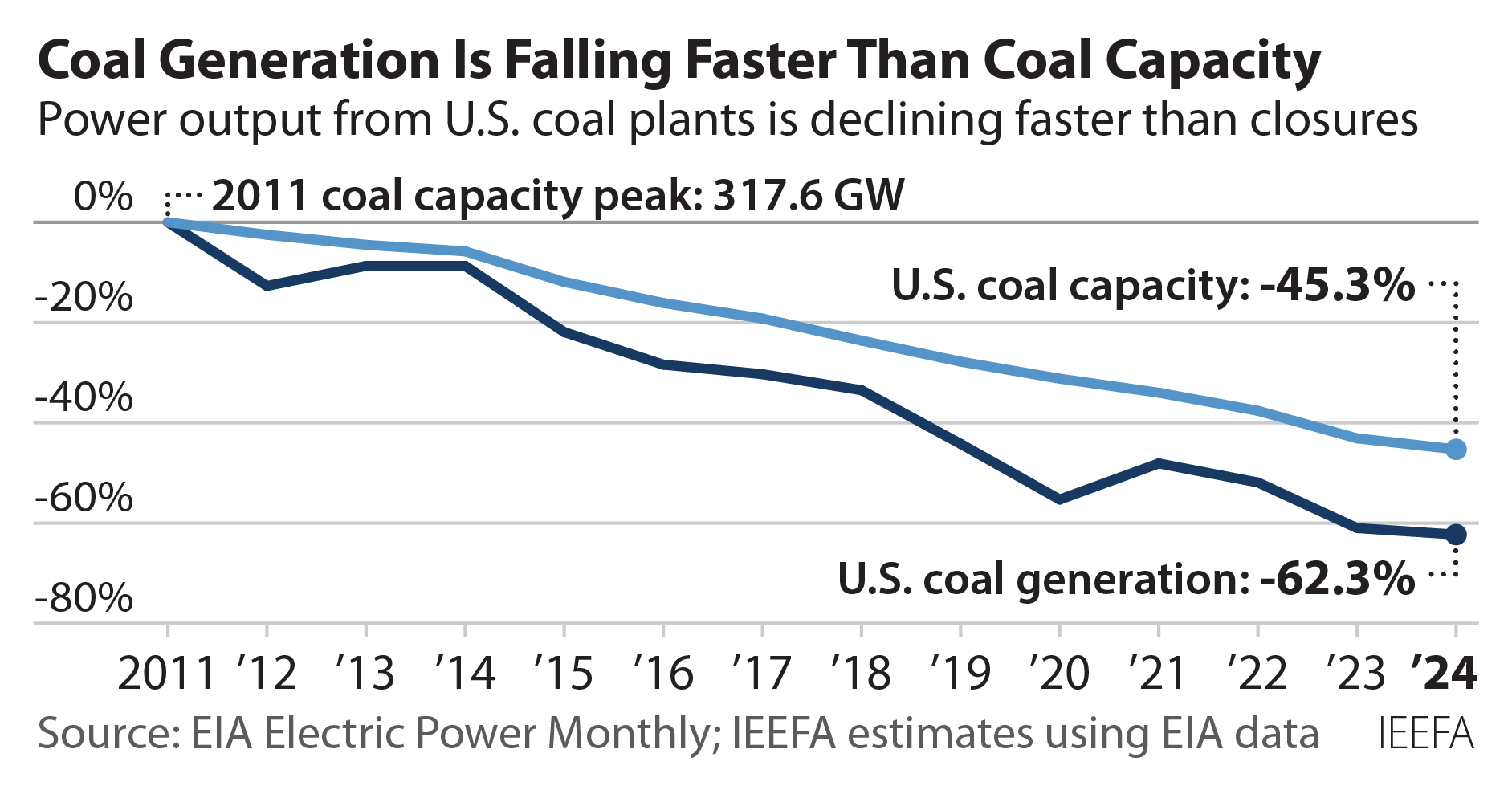

The end of coal use at these units would continue the trend of a remarkably steady and consistent shift away from the fuel in the U.S. The last new coal plant came online in 2013, as more economically competitive and cleaner sources of power became easier and faster to build, and the era of closing older, less efficient, and more expensive coal plants began. This era of retirements, along with a much smaller number of conversions to run on gas, will have reduced coal-fired generation capacity from its peak of 317.6 gigawatts (GW) in 2011 down to 164.6 GW by the end of this year. That’s a decline of 48%—nearly half—in just 13 years. IEEFA expects that halfway milestone to be reached in 2026.

Even with these coal plant closures, electricity generation in the U.S. rose to its highest level ever in 2024, driven by a sweeping transition to wind, solar, and gas, and more recently, battery storage. At the same time, coal-fired generation fell to its lowest level in decades, producing just 15.6% of the country’s power, less than utility-scale solar and wind, which produced 16.2%. In fact, in a clear sign that the remaining coal plants have been unable to produce competitively priced electricity most of the time, coal generation has been falling at an even faster pace than coal capacity has been retired.

The coal-fired units that are retiring or converting to gas this year represent a cross section of states and utilities, but they all share one key factor: age. The average age of the 17 units expected to close this year is 50; the youngest among them came online in 1987 (the massive 900MW Intermountain unit 2 in Utah); the oldest in 1962 (the 260MW J.H. Campbell unit 1 in Michigan). As coal plants age, they tend to become more expensive to maintain and operate, compounding their competitive disadvantage. The six units being converted to run on gas aren’t much younger—four are from the early 1980s and two are from the 1960s—and are generally expected to be sources of backup power at seasonal times of high demand.

In all of these cases, the power plant owners have been fully aware for years of the need to replace these aging assets, and have already built, or are finishing, other sources of power generation to ensure reliable electricity delivery continues to their customers. This process of long-term planning, together with the watchful eye of state regulators on utilities, is a key reason why the transition away from coal will continue.

A closer look at some of the closures taking place this year highlights the durability of the shift away from coal, as well as the challenges facing any effort to reverse those closures.

The Indian River 4 unit, for example, has already ceased operating, and was deactivated as a grid resource by PJM, the grid operator, on February 24. NRG had originally wanted to retire the unit in 2022, but was required by PJM to keep the unit available until some regional transmission system upgrades were completed. However, the plant hardly ran at all until the final weeks before it closed, when it ran simply to use up its remaining coal pile. This unit was the last remaining coal unit in Delaware.

Another two units, Cholla 1 (116 MW) and 3 (271 MW), owned by Arizona Public Service (APS), have also ceased operating. As reported by The Arizona Republic on April 9, the company said, “APS stopped generating electricity at Cholla last month, in accordance with federal regulations and due to increasing costs that have made the plant uneconomical to operate … At this time, APS has already procured reliable and cost-effective generation that will replace the energy previously generated by Cholla Power Plant.” While the plant was specifically mentioned in a presidential news conference on April 8 as one that would be kept open, it remains unclear how that could happen or who would pay for it.

In Washington state, the planned retirement of Centralia unit 2 (670 MW) later this year will not only mark the end of coal-fired power in the state, but it would also mean the end of coal use at power company TransAlta, which operates electric plants in nine U.S. states and multiple Canadian provinces.

Other power companies are expected to exit coal this year too. In May, CMS Energy, which provides power to much of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula under the Consumers Energy banner, is set to close its final three coal units when it retires J.H. Campbell, a 1,435MW plant near Grand Rapids on the shores of Lake Michigan.

WEC Energy, which delivers power to 1.9 million electric customers in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, reiterated to investors in March that it will eliminate coal use by 2032—and use it only as an emergency backup by the end of 2030. This year, WEC will close South Oak Creek units 7 and 8 (616 MW), between Milwaukee and Racine, Wisconsin.

Xcel Energy, which serves 3.9 million electric customers in eight central U.S. states, will take a major step toward its own goal of exiting coal by 2030 when it closes Comanche 2 (335 MW) in Pueblo, Colorado, and stops using coal at Pawnee, a 505MW unit in eastern Colorado that the company is converting to burn only gas. Xcel also has a small stake in another coal unit closing in Colorado this year, Craig unit 1 (427 MW), which is majority-owned by Tri-State Generation and Transmission. Tri-State plans to close two other units at Craig, the 410MW unit 2 in 2028, and the 448MW unit 3 in 2029, as it works to end its coal use in Colorado and New Mexico by 2030.

Xcel also has an agreement with Colorado to begin reducing operations at its long-troubled, 750MW Comanche 3 unit in 2025. This unit came online only in 2010, but suffered frequent and lengthy downtime, and is now scheduled to fully close by 2030.

Another big coal plant closure still expected to happen is in western Utah, where the Intermountain Power Agency plans to retire two 900MW coal-fired units this summer, though the move has been contested by the state. The Intermountain plant provides much of its electricity to California, including the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, but its power contracts will end in July. In an ambitious project, Intermountain has replaced the coal facility with a new, 840MW combined cycle gas plant designed to initially run on 30% hydrogen, which will be produced near the plant by Mitsubishi, the maker of the plant’s turbines, and stored in underground salt caverns owned by Chevron. It would be among the first plants in the world to use such a high level of hydrogen to produce power.

But it is the units that are being converted to burn gas instead of coal that may be making the coal industry most nervous. Six of the 23 units are in this group, including Naughton 1 (156 MW) and Naughton 2 (202 MW) in western Wyoming, the largest coal-producing state in the country. In November 2024, Rocky Mountain Power (RMP), the subsidiary of PacifiCorp that owns the Naughton plant, applied for approval to convert these two units to gas. Once approved, RMP expects to stop coal use by the end of December, 2025, and return the units to service using gas by May 2026. This short six-month turnaround, and the low costs cited by RMP, highlights how quickly many existing coal plants could switch fuels.

In West Virginia, the second-largest coal-producing state and a big gas producer, American Electric Power (AEP) has raised the possibility of converting two big coal plants, Amos and Mountaineer, and the CEO of FirstEnergy said in February that it plans to replace its coal generation in the state with new gas plants over the coming decade. Both companies are dealing with an aging and uneconomic coal portfolio. In 2024, West Virginia produced 87% of its power with coal, and the growing threat from gas has unsettled the powerful coal industry.

Despite efforts to impede the transition away from coal, this year’s announced closures highlight just how difficult that would be. Rising costs at aging coal facilities, power companies’ long-term investments and planning in new generation resources, and deep involvement by state regulators to ensure reliable power and keep a lid on electricity rates are all providing momentum for this shift. In addition, the short build times, flexible scale, and greater certainty of fuel costs continues to accelerate the construction of solar facilities and dispatchable battery storage. Along with wind and gas, all of these factors signal coal’s limited future.