Coal logistics consolidation: A net-zero productivity play for Australia

Key Findings

Fragmented operations in the coal supply chain – with nine different export ports and nine different rail operators – are complicating the sector’s net-zero ambitions.

Decarbonisation pathways are being stalled by competing alternatives that are not yet ready for commercial deployment, but decisions need to be made within the decade if we are to reach net zero by 2050.

Productivity could be boosted by natural attrition at some of the coal ports and rail lines, which would otherwise attract stranded asset investments.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

Australia’s coal export industry is facing an inefficiency problem that’s been brewing for years but is now reaching a critical point. With net zero on the agenda at the government’s productivity round table this week, Australia’s fragmented coal logistics network offers a lesson in how not to achieve productivity in infrastructure investments for a net-zero emissions outcome.

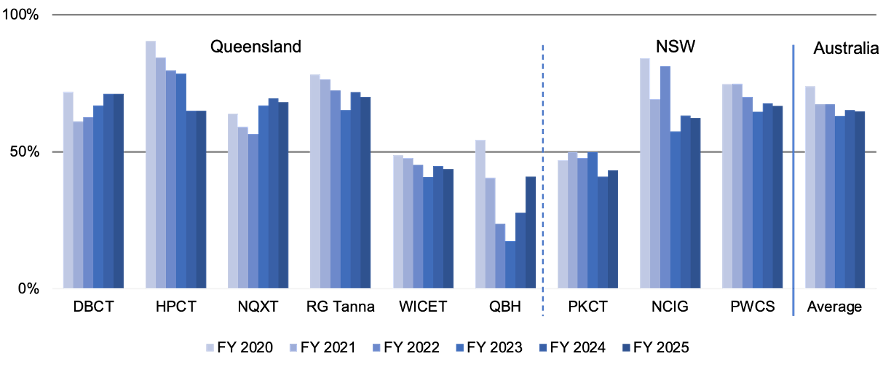

Australia exports around 352 million tonnes (Mt) of coal annually, through nine separate terminals scattered along the NSW and Queensland coastlines connected by nine different rail infrastructure operators. These ports are operating at just 65% capacity utilisation overall. That’s like having nine sets of infrastructure when you only need six, but continuing to pay for all the costs.

The problem gets worse when you look at individual terminals that operate at below 50% capacity. Port Kembla Coal Terminal (PKCT) has lost two of its five servicing mines since 2024, leaving the remaining three mines to shoulder increasingly concentrated costs. Queensland Bulk Handling (QBH) in Brisbane is down to just two shippers after recent bankruptcies, facing a brutal choice: accept a 50% rail tariff increase (on the West Moreton rail line to Brisbane); or send coal elsewhere. Meanwhile, Wiggins Island Coal Export Terminal (WICET) at Gladstone has three remaining shippers, with one – Coronado Resources – facing a liquidity crisis that could leave just two viable operators remaining. As Australia’s most recent coal terminal, built in 2015, the others from the original eight shareholder mining companies have since liquidated their position in WICET .

When shippers drop off these networks, the remaining operators face what economists call “cost socialisation” – basically, the same infrastructure costs get spread among fewer users, driving up per-tonne charges.

Faced with higher charges, miners re-evaluate their mines or look to export from alternative ports, within existing transport infrastructure. In the case of PKCT, miners transport coal via a mix of rail and road to the port and the remaining three mines are due to cease mining by about 2030. During periods of high port prices, mines have shipped coal north to the more competitive Newcastle export terminal. For QBH, Queensland Rail is proposing to spend upward of $120 million on expanding the network for the remaining two mines, in tandem with the increased tariff. One of those miners, Yancoal, said it may have to close its mine or else resort to ad-hoc railings. Constructing an alternative rail link north to Gladstone has been previously considered and deemed to be uneconomic. A common rail line (Central Queensland Coal Network) serves both Gladstone export terminals.

Figure 1: Port capacity utilisation trend – below 50% for three terminals

Figure source: Annual reports, NSW Coal Services, port trade throughput statistics, IEEFA.

The net-zero challenge facing this sector has several elements. Firstly, previous ambition around diversification to green hydrogen exports appears to have reached a dead end. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concerns from financiers and investors had driven diversification strategies for coal-focused bulk export ports. However, ports that were banking on diversifying into green hydrogen exports have been hit by a wave of project cancellations. The Brisbane and Gladstone green hydrogen projects have been declared uneconomical. Their main proponent, Fortescue, has pivoted from ambitious green hydrogen export plans to using hydrogen locally for its own operations.

Secondly, reducing direct emissions from the coal supply chain involves replacing diesel for heavy vehicle equipment, with zero- or low-emissions alternatives. This is essentially a massive technology transition problem – like the automotive industry’s shift to electric vehicles, but with much longer asset replacement cycles and higher stakes. Rail freight operations contribute 95% of the rail sector’s direct emissions – about 4Mt of CO2-equivalent annually – while coal mining adds another 30Mt.

Critically, the rail freight industry needs to make fleet replacement decisions within the next 12 years to have any hope of achieving net zero by 2050, but the technology pathways remain frustratingly unclear. Battery-electric and hydrogen fuel cell locomotives are still in demonstration phases, with commercial availability not expected until after 2030. University of Queensland research with Aurizon shows that different rail corridors will require different solutions: battery power for shorter routes like the 200km Gladstone-Moura corridor; but hybrid battery-hydrogen systems for longer routes. The timeline for action is closing. With rolling stock replacement cycles of 25-30 years, decisions made in the next decade will determine emissions trajectories through to 2050.

However, the policy environment currently presents disincentives for coal supply chain decarbonisation. For example, miners benefit twice from the Diesel Fuel Rebate Scheme: directly, through subsidised diesel purchases for large mining equipment; and indirectly, via the rail tariffs for diesel used in locomotives delivering coal to the ports. This creates inertia on decarbonisation investments such as electrification of mining fleets and rail freight locomotives, which require significant infrastructure including charging stations, low-carbon generation capacity and energy storage systems. A GlobalData survey found this a major barrier to investment in electrification in mining.

The productivity argument for logistics consolidation is compelling in its simplicity. If the three most vulnerable ports – PKCT, QBH, and WICET – were to close, overall system utilisation would increase from 65% to about 70%, with the removal of 55Mt of redundant export capacity, depending on whether mines shut or redirect coal elsewhere. Further, rail complexity would be simplified, streamlining decarbonisation decisions for the sector. The Australasian Railway Association’s research shows that the current fragmented approach creates “a leadership vacuum and lack of ownership” around decarbonisation, hampering industry collaboration. Meanwhile, Aurizon is reported to be selling a stake in its Queensland rail network.

Climate change is a global problem and Australia’s contribution comes mainly from Scope 3 emissions exported by the coal sector. This week’s productivity round table should view this sector not only as critical to Australia meeting its net-zero targets and minimising climate change, but as a case study in how fragmented infrastructure undermines both productivity and decarbonisation goals. Policymakers should focus on removing barriers to natural market consolidation while ensuring coordinated infrastructure development for whatever technologies prove commercially viable.

Our current approach of supporting nine separate terminal operations and nine rail operators, with their own incompatible infrastructure plans and stranded asset risks, isn’t just inefficient – it’s actively counterproductive to Australia’s net-zero ambitions.