Expensive, underutilized Jamshoro coal plant exposes Pakistan’s power sector overcapacity

Download Briefing Note

Key Findings

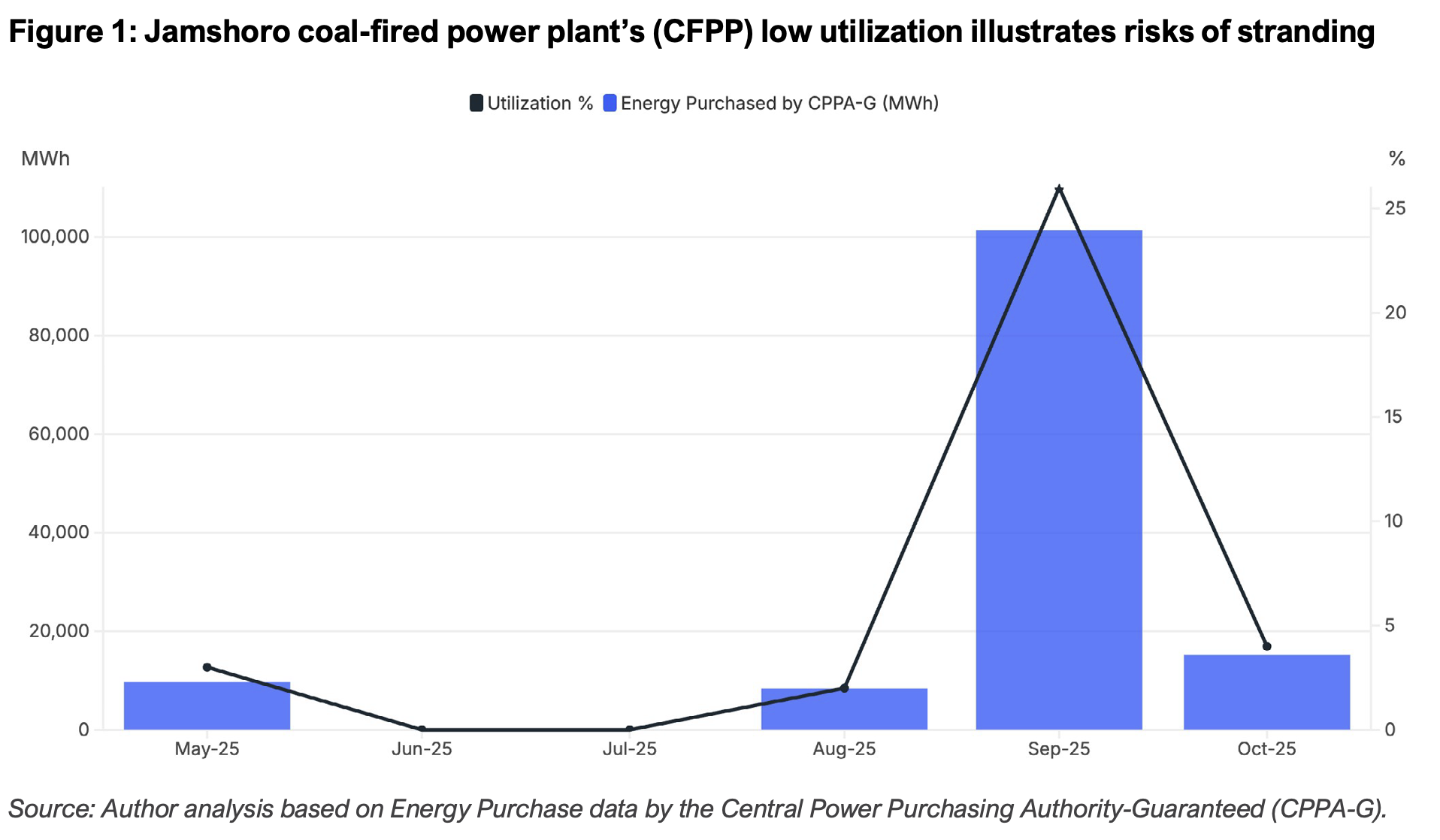

Since its commissioning in May 2025, Pakistan’s Jamshoro coal-fired power plant (CFPP) has averaged a 6% dispatch rate over the past six months. Utilization is projected to remain far below technical minimums required for reliable and efficient long-term operations, even under high-demand scenarios.

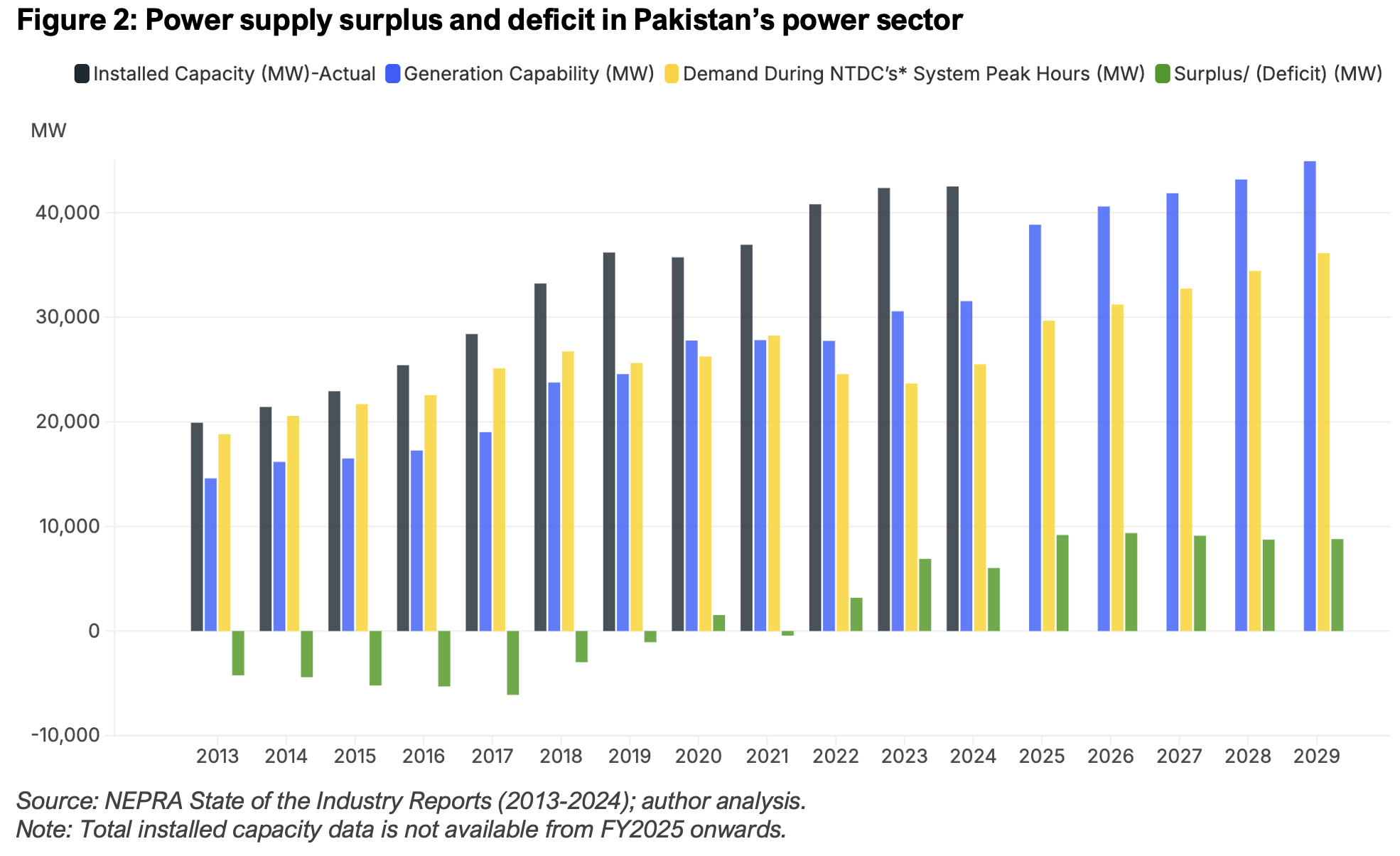

Pakistan’s national grid has a significant surplus of 10–12 gigawatts (GW). Energy sales contracted by 9.4% in the financial year (FY) 2023 and by 2.83% in FY2024, while capacity payments increased from PKR0.97 trillion in FY2022 to PKR1.90 trillion in FY2024 — a 96% rise over two years.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) financed Jamshoro CFPP through loans to the Government of Pakistan, at a time when the bank was already transitioning away from coal. Repayment on inflated loan rates depends on revenue from already debt-burdened distribution companies (DISCOS), adding to the chronic circular debt issue.

The Jamshoro project offers an opportunity for ADB to reassess its own investments and consider the plant for early retirement. Restructuring its debt and evaluating feasibility scenarios could provide financial and climate benefits, aligning ADB’s energy transition goals and Pakistan’s clean energy commitments.

Located on the outskirts of Jamshoro, Pakistan, the 880-megawatt (MW) Jamshoro thermal power generation complex has hosted a mix of power generation units running on oil and gas for over three decades. Skyrocketing oil prices, declining domestic gas reserves, and the addition of newer, more competitive power generation technologies have substantially reduced the utilization of the generation complex in recent years — to the extent that the electricity dispatched has reached its lowest levels since 2019.

Jamshoro Power Company Limited (JPCL), the entity managing the complex, has initiated the process to de-license the four old units, which are under active disposal. Removal of old and redundant thermal plants from the national grid, which currently has a significant 10–12 gigawatts (GW) surplus, benefits the power sector by eliminating inefficient capacity while contributing to national decarbonization goals. However, even more efficient fossil plants are difficult to justify if they are not needed. The newly commissioned 660MW super-critical coal-fired Unit 5 at the Jamshoro thermal power plant site is one such example.

Since its commissioning in May 2025, the plant’s dispatch rate has been sporadic, averaging 6% over six months.

This chronic underutilization is projected to persist for the foreseeable future. The latest Indicative Generation Capacity Expansion Plan (IGCEP) (2025-2035) predicts a maximum utilization of just 26% for the plant, even under a high-demand scenario in 2027. In other scenarios, such as increasing solarization and low power demand, the plant output reduces to near zero for most of the next decade. Across all scenarios, utilization rates are forecasted to be far below the technical minimums required for reliable and efficient long-term operations.

Why build the Jamshoro CFPP in the first place?

The national grid’s surplus and its associated burden of rising capacity payments are well-recognized challenges since 2022–2023. High electricity tariffs and a declining industrial base, combined with the rapid adoption of distributed solar, have led to a decrease in energy sales. Meanwhile, fixed costs associated with debt servicing and equity returns for generation assets remain unchanged, resulting in a higher per-unit capacity charge. Energy sales declined by 9.4% in the financial year (FY) 2023 and by 2.83% in FY2024. At the same time, calculations by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) show that capacity payments increased from PKR0.97 trillion in FY2022 to PKR1.31 trillion in FY2023 and PKR1.90 trillion in FY2024 — a 96% rise over two years.

The addition of the Jamshoro coal-fired power plant (CFPP) to the national grid will not only exacerbate the problem of generation overcapacity, but it will also put additional stress on Pakistan’s limited foreign exchange resources, as 80% of the coal required for operation will have to be imported.

Although it was conceived more than a decade ago in 2013, the Jamshoro CFPP started operating only recently. In 2014, a financing agreement was signed with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for an initial USD840 million loan (later revised to USD658 million). While the bulk of the loan came from ADB’s Ordinary Capital Resources, USD30 million was allocated from its highly concessional finance window, the Asian Development Fund.

The project remained at the conceptual stage for another four years until 2018, when the Private Power Infrastructure Board (PPIB) issued the Notice to Proceed (NTP). Construction began in 2019 following approval by the Executive Committee of the National Economic Council (ECNEC).

Pakistan had an installed power generation capacity of 23.5GW and an average available capacity of 14GW when the Jamshoro CFPP was planned. Many heavy fuel oil (HFO)-fired plants, which supplied 34% of the total power generation, were offline due to fuel and funding shortages, resulting in widespread load shedding and a 4–5GW energy deficit.

ADB’s financing aimed to reduce HFO dependence, lower generation costs, and narrow the supply-demand gap. Imported coal, which was significantly cheaper than HFO, was viewed as a viable short-term solution, with domestic coal reserves expected to be explored later. Therefore, the plant was designed on an 80:20 blend of imported and local coal.

Several of these assumptions did not materialize. By the time construction began in 2019, Pakistan’s surplus capacity problem was already emerging. Three imported coal plants with a 3.6GW combined capacity were operational, along with three liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants with a total capacity of 3.6GW.

During this period, Pakistan’s first domestic coal-based power plant, the 660MW Engro Thar CFPP, was also commissioned, along with several wind and hydro power projects. Consequently, installed generation capacity reached 36GW, while available generation capability was 26GW, reflecting factors such as plant outages, fuel availability, seasonal hydropower variations, and transmission evacuation limits. The economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic also meant that power demand rose by a mere 2.4% in 2020, compared with the National Transmission and Despatch Company’s (NTDC) highly optimistic projection of 4.1%. As a result, the grid recorded its first-ever surplus of 1.5GW.

Meanwhile, another 2.7GW of Thar coal capacity and a 1200MW LNG plant were already in advanced construction and expected to come online by 2023. This raises an important question: why was Jamshoro CFPP allowed to proceed in 2018 when grid overcapacity was apparent and predicted to increase?

Evidence suggests that at least some branches of the government recognized the plant’s redundancy. A Fuel Price Adjustment Petition on the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) website includes a dissenting note by NEPRA members, warning that the addition of Jamshoro CFPP would exacerbate the overcapacity issue, and that transmission bottlenecks preventing surplus power evacuation would need to be resolved before a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) could be approved for JPCL.

A second 660MW unit for the Jamshoro CFPP was ultimately canceled due to these concerns and a lack of funding. This raises the question of why the first unit did not undergo similar scrutiny. Examining the project’s financing may explain why it was allowed to proceed.

Financing arrangements for the Jamshoro CFPP

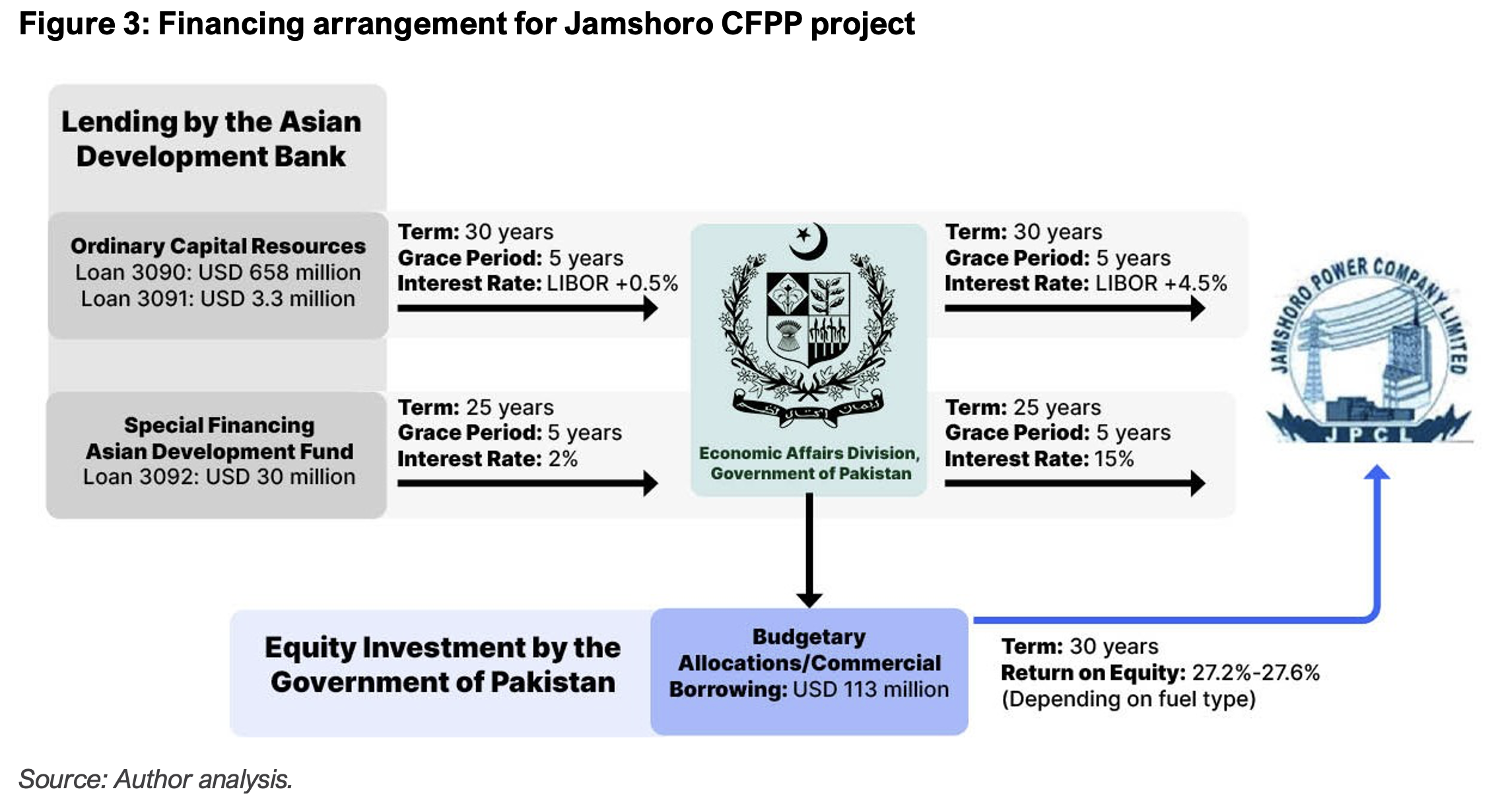

According to project documents, financing for the Jamshoro CFPP was provided with an 86.24:13.76 debt-to-equity ratio. As mentioned previously, debt financing was arranged through two ADB loans totaling USD658 million (Loan 3090) and USD3.3 million (Loan 3091), sourced from the institution’s Ordinary Capital Resources, along with a USD30 million concessional loan from ADB’s special financing arm. Over the years, the Government of Pakistan’s (GoP) equity has amounted to USD113 million.

Instead of lending directly to the project, ADB’s loans are routed through the government at a significant markup. For instance, Loan 3090 (USD658 million) was lent to the GoP Economic Affairs Division (EAD) at an interest rate of London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) +0.5%. In contrast, the government’s subsidiary loan arrangement provided funds to the Jamshoro CFPP project at a rate of LIBOR +4.5%. Similarly, Loan 3091 (USD30 million) was provided at a markup of just 2% by the ADB but was re-lent to the project at a flat interest rate of 15%.

While this intermediary lending structure is common for projects supported by multilateral development banks (MDBs), the lending margin secured by the GoP may have influenced the decision to proceed with this project despite the apparent grid surplus. Contrary to the misperception that gross-up lending margins could raise revenue for the state exchequer, repayment on these inflated rates would ultimately come from power consumers through the government’s distribution companies (DISCOS), which are already burdened by substantial unpaid debts. By 2018, circular debt resulting from these revenue shortfalls had become a chronic issue, and any additional costs would have further intensified the problem.

MDB loans can be cancelled at the borrower’s request

Loan cancellations by MDBs are not uncommon. In 2022, the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Fund canceled a USD172 million loan for the proposed second unit of Jamshoro CFPP at the government’s request. ADB’s loan covenants also allow borrowers to cancel undisbursed amounts. Given rising capacity payments from underutilized generation and the growing concerns over the unsustainability of coal-fired power, the government had grounds to reassess the need for this financing.

Could ADB have cancelled the loan independently after realizing that it was no longer needed? Under its rules, ADB does not unilaterally cancel a committed loan unless there is a breach of the agreement. However, this should not have prevented ADB from revisiting the project’s relevance with the GoP through bilateral consultations, as it has done elsewhere. For example, ADB plans to cancel or redirect a USD408 million loan to Bangladesh in 2025 due to implementation delays.

This raises the question of why the loan for Jamshoro CFPP remained in place despite a significant four-year delay between the loan sanction and the project commencement. Both the GoP and ADB had sufficient time to consider alternative uses — such as enhancing the grid’s resilience or building energy storage — rather than moving ahead with a project that clearly appeared unnecessary even before construction began.

ADB’s shift away from coal-fired investments could provide a way out

The Jamshoro CFPP loan was ADB’s final investment in coal-based power globally. The bank has not invested in any other coal project since 2013. Its shift away from such investments was formalized in the 2021 energy policy framework, after which it initiated various programs to enhance clean energy generation across Asia. For instance, the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) provides a blend of concessional and commercial financing to coal-dependent countries to transition towards cleaner energy generation. It has initiated ETM facilities in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Kazakhstan, although the mechanism has yet to deliver a successful pilot project based solely on ADB’s support and transaction design. In fact, the program faced a major drawback as Indonesia’s ETM-driven retirement plans for the Cirebon 1 CFPP were canceled after lengthy negotiations amid concerns over the high cost of early retirement.

As ADB searches for a successful coal phaseout case, it could begin with a coal plant built with its own funds. The bank’s 2022 pre-feasibility assessment on retiring thermal power plants in Pakistan, including coal-fired ones, suggests that Jamshoro CFPP could be considered for early retirement. Since most of the plant’s financing was under commercial terms, restructuring its debt could yield dividends, providing early compensation to its sponsors. However, this would require a feasibility analysis of early retirement scenarios, supported by both the GoP and ADB.

If pursued, this could deliver substantial financial benefits for Pakistan’s power and climate sectors. A recent study indicates that the accelerated closure or repurposing of CFPPs, such as the one in Sahiwal, could save Pakistan nearly USD5 billion in continued capacity payments and reduce carbon dioxide emissions by up to 38 million tonnes.

Overall question of power needs

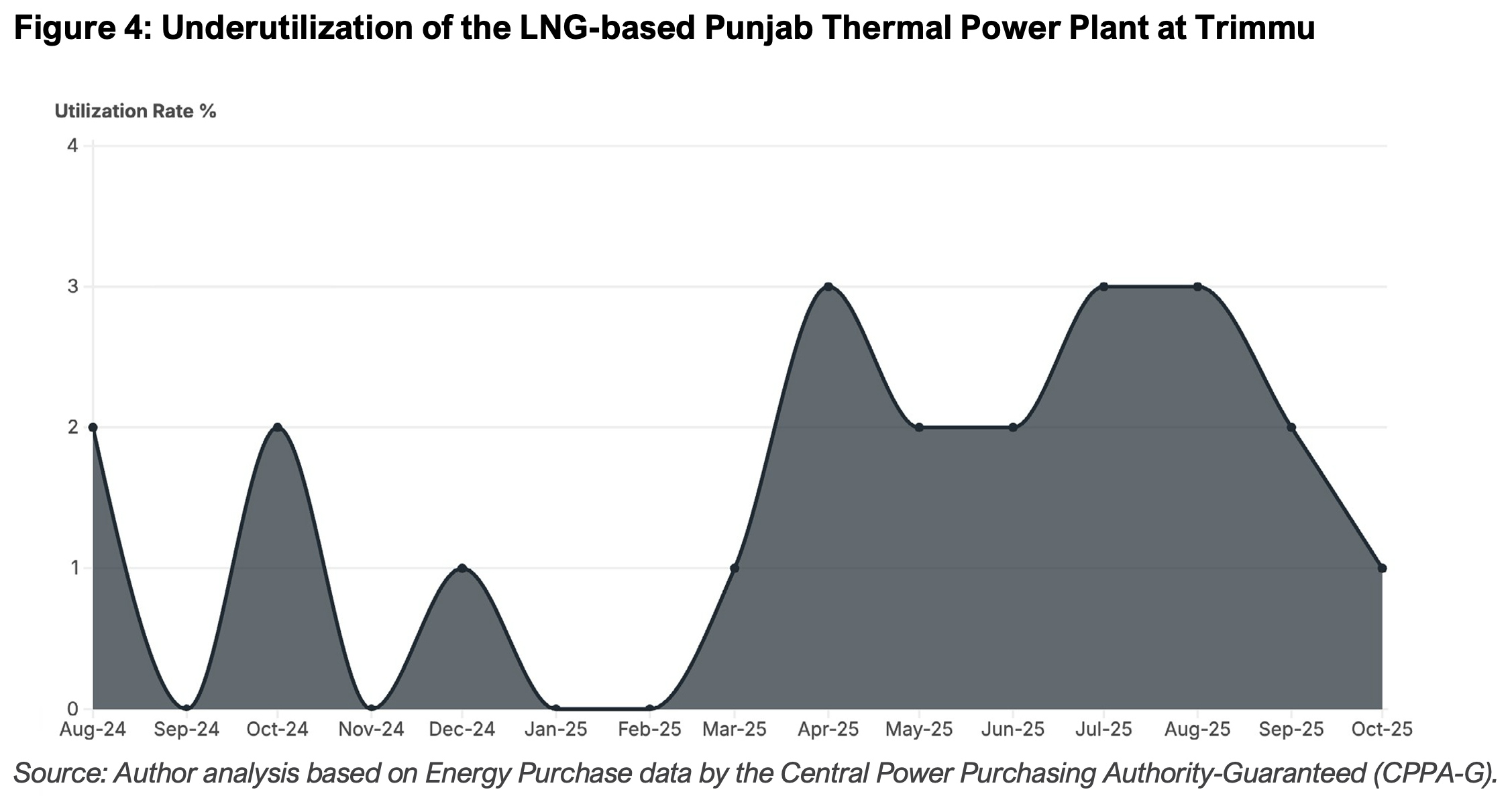

For Pakistan, early retirement of CFPPs can also be an opportunity to mitigate its overcapacity crisis. Jamshoro power plant is not the only one that is underutilized. This problem pervades the country’s entire power generation fleet, with an average utilization rate of 34% in 2024, amid a rapid shift to distributed solar by consumers seeking energy independence. Just like Jamshoro CFPP, plants running on LNG, such as the one in Trimmu, also have chronically low dispatch, averaging barely 3% between August 2024 and October 2025, despite their capacity payments continuing to rise.

If Pakistan’s energy demand does not increase in the coming years, underutilization is likely to persist or worsen. In the near term, low dispatch rates for many power plants will continue as more consumers adopt solar with battery storage. Over the long term, several hydroelectric projects with a collective capacity of 10GW are expected to join the national grid over the next decade, further reducing the dispatch of fossil fuel-based plants. This is because their reliance on dollar-dominated fuel imports will continue to make them more expensive to operate than hydropower units.

As the government rethinks its dependence on imported fuels, Jamshoro CFPP could be a starting point for diversification. The government is considering plans for converting the plant to operate on 100% domestic Thar coal. Such a shift could be technically possible but would require additional capital investment in the plant as well as in fuel transport and handling equipment. Assessments would be needed to evaluate if the resulting all-in long-run marginal cost is worthwhile or if the plant would remain underutilized.

While converting Jamshoro to Thar coal may address low utilization for this specific individual asset, it could still be an issue for plants that remain dependent on imported fuels. Retrofitting costs, the scalability of Thar coal production, and financing constraints could impact the timing and feasibility of converting other imported coal-fired projects to local coal. Although LNG has proved to be too expensive for power generation in Pakistan, some government planners view coal plants as necessary for energy security and system stability. Jamshoro may be physically located at a critical transmission junction from the South to the North, but a surplus of idle capacity will not serve the country’s interests.

Conclusion

As a newly commissioned plant dependent on imported fuel, Jamshoro CFPP is expensive under both short- and long-run marginal cost measures. Its near-zero utilization reflects this economically — it consumes money while providing minimal economic value. Converting the plant to domestic coal will incur more capital costs and may not result in materially lower operational expenses, given its current capital recovery needs. ADB financed this plant at a time when it was already transitioning away from coal-fired power projects, and the limited need for this project was clear. Circular debt was already chronic across the power sector, and the Jamshoro CFPP would have offered no relief. ADB is currently seeking opportunities to decarbonize national energy portfolios but has had little success with projects in which it is not directly involved. The Jamshoro project may offer an opportunity for the bank to reassess its own investments. For the GoP, this could support financial prudence and reinforce its climate commitments to clean energy and economic perseverance.