Singapore’s clean electricity success rests on support from exporting nations

Key Findings

Singapore’s serious commitments to shift its energy dependency from natural gas power imports could be at stake. This is due to Indonesia’s lack of clarity on power export regulations and Malaysia’s ban on renewable energy exports.

The potential for clean energy export might stimulate Indonesia’s long stagnant domestic renewable energy market, but three factors summarized in this commentary can make or break these plans.

Malaysia’s limiting non-renewable electricity export to Singapore to meet its own climate goal, announced in October 2021, may also have the Indonesian government think twice.

Singapore’s serious commitments to shift its energy dependency from natural gas power imports could be at stake. This is due to Indonesia’s lack of clarity on power export regulations and Malaysia’s ban on renewable energy exports. This could all jeopardize Singapore’s ambitions.

In November 2021, the Singapore Energy Market Authority (EMA) announced the first out of two requests for proposals (RFP) for reliable, competitive, and low-carbon non-intermittent import of a total 4 GWac, amounting to about 30% of Singapore’s electricity needs by 2035.

By April 14, there were 25 potential importers listed on the EMA website, forming at least five consortiums with plans to jointly develop solar powered projects in the Indonesian archipelago:

The potential for clean energy export might stimulate Indonesia’s long stagnant domestic renewable energy market, but three overarching factors can make or break these plans.

Firstly, Indonesia’s current regulation allows no party other than the owner of the Power Business Area Permit (Wilayah Usaha or “Wilus”) to export power. At the current state, only two entities are legally allowed to perform power export without additional permitting process, which is the state-owned Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) and its subsidiary, PLN Batam.

Obtaining Wilus from the Directorate General of Electricity is time-consuming and complicated. Significant risks persist for current bidders, especially those who do not include PLN subsidiaries in their consortium.

Secondly, supplying power, especially from renewable sources, might be challenging for PLN and PLN Batam. Legally, three conditions must be met by any Wilus owner to conduct cross-border power sale: the selling price does not contain any subsidies, non-interference in the power supply quality and reliability in its operational area, and that local power needs are fulfilled first.

In a recent public webinar, industry representatives including the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (Batam Chapter), presented arguments about how PLN Batam cannot meet their power demand, especially when renewable sourced power from solar energy is the only viable option in the area. Another spokesperson from PLN Batam also admitted their struggle to cope with renewable energy demand from their industrial customers.

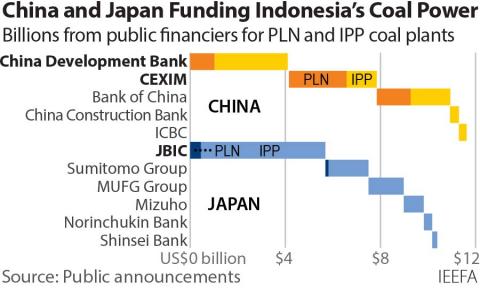

With limited investment capacity, and fully stretched cash flow, one strategy is for PLN to become the transmission operator and provide power wheeling service for export to Singapore. This would however prove far less profitable, compared to bidding into the generation business.

Thirdly, Indonesia’s Local Content Requirements have long created a vicious circle for the local manufacturing PV industry. Investors want to reap returns on their investment, before adding more funding to the country. Yet, the domestic solar industry has not been able to grow at speed due to low market absorption.

It is not yet clear to bidders whether the current Ministry of Industry’s regulation on local content would apply to non-PLN projects outside of government funding. If it does, this could lead to higher costs and lower quality products, considering there is not yet a Tier 1 solar manufacturer operating in Indonesia which is crucial for bankability purpose, not to mention the fact that domestic manufacturing capacity is only at around 500 MW/year currently.

The GW export market to Singapore along with the recent 2.3 GWp rooftop solar commitment from local C&I installers could present a potential solution for the lack of domestic market growth. However, it would need to be done in stages facilitated with realistic expectations of local content contribution, along with adjustments to the current regulation.

Deep waters

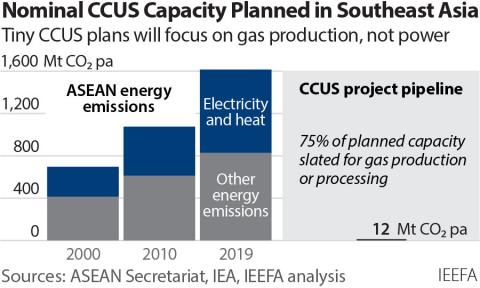

Malaysia’s limiting non-renewable electricity export to Singapore to meet its own climate goal, announced in October 2021, may also have the Indonesian government think twice. This is primarily because the carbon emission reduction ownership will be claimed by EMA through commercial means, as explained in the RFP document, while Indonesia is still lagging far behind on its Nationally Determined Contribution target.

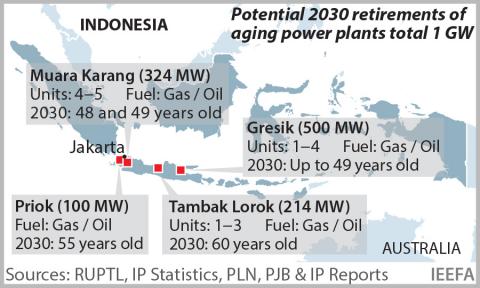

An alternative for Singapore might come from the A$30 (US 20) billion Australia-Asia Power Link project. In April 2022, Singapore-based Sun Cable submitted its Environmental Impact Statement to Australian authorities. Designed to support Singapore with 17-20 GW solar farm and 36-42 GWh of battery energy storage in Australia’s Northern Territory, the fate of the 4,200-kilometer (2,600-mile) subsea cables rest on authority approval in the Indonesian waters.

Sun Cable’s project had progressed in September 2021, after the route through Indonesian waters was approved, but no formal permits or licenses other than permits to carry out subsea surveys have been issued. This postulates risk from any regulatory changes due to Indonesian political dynamics.

Within the next couple of months, it appears the Singaporean government will work hard to negotiate with its Indonesian peer. Or else, however attractive the proposals of the private bidders, any unclear permit and export license could stall projects.