Nowhere to go but down for U.S. coal capacity, generation

Recent projections of sharply higher electricity demand growth are creeping into forecasts for coal plant retirements, prompting some energy analysts to revise their closure outlooks downward. IEEFA is not among them.

Our research shows that U.S. utilities have plans to retire or convert to gas 68,789 megawatts (MW) of existing coal-fired generating capacity from 2025-2030. This is almost twice the 36,425MW total included in data released by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) in its September Electric Power Monthly report.

EIA’s numbers are not wrong, per se, they are just limited. The agency’s numbers reflect information provided to them by utilities; IEEFA’s data includes public announcements made by the companies, financial filings at the Securities and Exchange Commission and long-term resource plans submitted to state regulators. Another important distinction is that EIA does not include coal-to-gas conversions in its retirement data since the plant is not technically being retired. IEEFA counts those plants as retired when the conversion results in the end of coal combustion at the facility. This fact alone accounts for 12,273 MW of the difference in the two estimates between 2025-30.

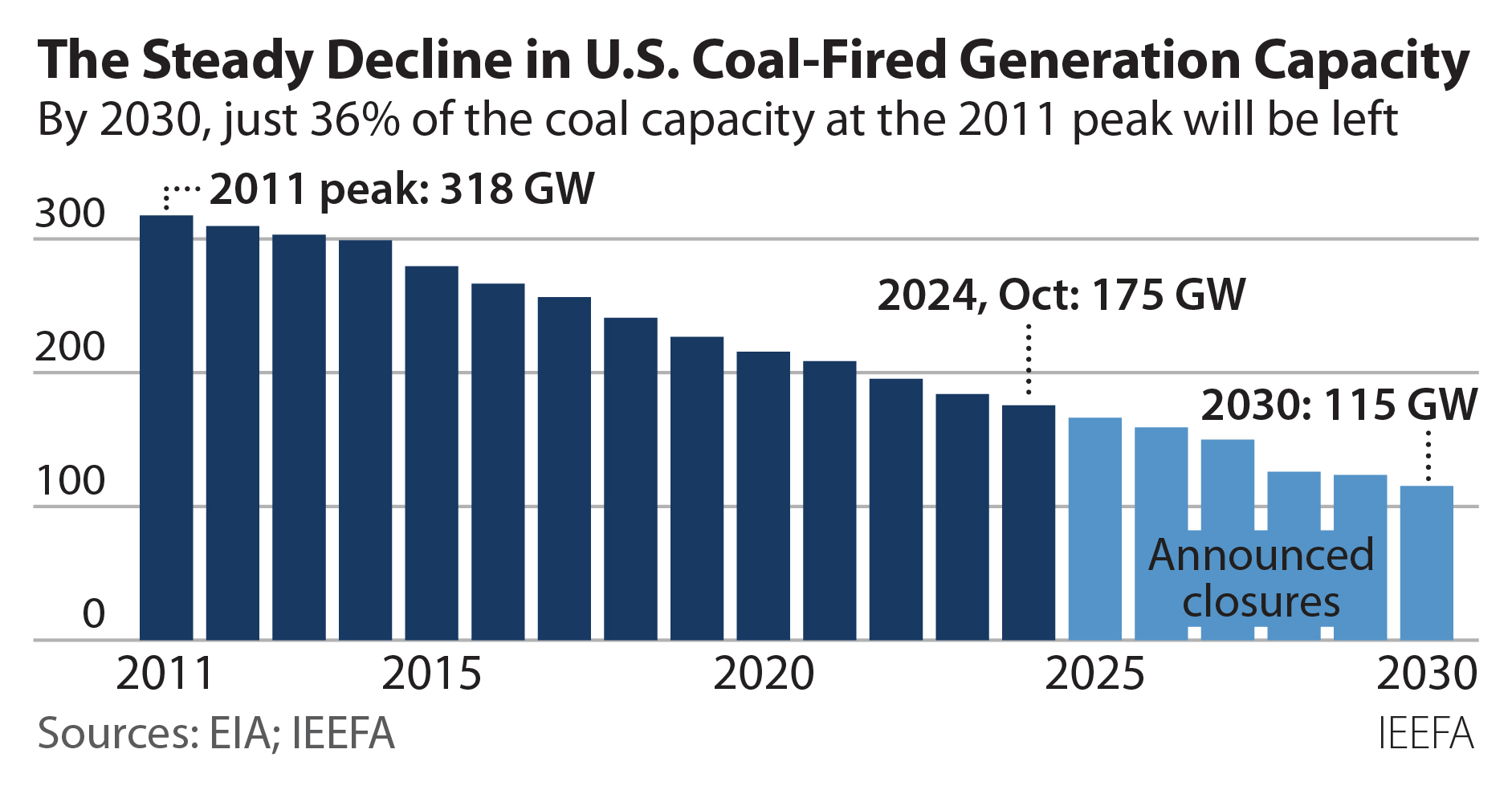

The long-term reality in the ongoing move away from coal generation is the transition has been remarkably consistent, averaging about 10,000 MW of capacity closures annually. Installed U.S. coal-fired generation capacity peaked at 317,600 MW in 2011. That was also the last year coal accounted for more than 40% of annual electricity generation, hitting 42.3%, after having averaged 48.6% in the previous decade.

It has been steadily downhill since. From 2011-20, 103,900 MW of capacity stopped burning coal, and the remaining operational coal plants started running much less. During the pandemic in 2020, coal’s share of generation fell below 20% for the first time. This year, coal’s share of generation is expected to barely top 16%, and IEEFA expects operating coal capacity to be at or below 175,000 MW by the end of the year.

Based on current announcements and IEEFA research, we expect operating coal capacity to continue its steady decline for the remainder of the decade, pushing the total down to about 115,000 MW in 2030. That means in 2030, 63.8% of the peak total—203,000 MW of coal-fired capacity—will have been closed.

Looking beyond that marker, IEEFA believes it is possible that all the remaining 115,300 MW of coal capacity still online at the end of 2030 could be shuttered by 2040.

Three key factors support that outlook. For starters, companies already have announced plans to retire 38,921 MW of that remaining post-2030 capacity, or 33.7%, between 2031 and 2040.

Second, age. More than 8,100 MW of currently operating coal capacity will be at least 60 years old by 2030, but plant owners have not yet announced retirement dates. It is highly unlikely any of those units will still be operational by 2040, given the increase in maintenance costs and the decline in performance that go hand in hand with aging coal plants. Another 20,000MW of coal-fired capacity will be at least 50 years old by 2030, putting them at or near their expected operational lifespans.

Finally, even the remaining coal plants are likely to operate significantly less frequently, continuing another decade-plus trend that has seen the capacity factor (the amount of power produced divided by the maximum amount that could be produced over a given period) at operating coal plants fall steadily since 2011. That peak year, U.S. coal plants posted an annual capacity factor of 62.8%, a level that has not been approached since. Coal plants have not even hit that performance mark on a monthly basis since 2021.

During the 2010s, coal’s annual capacity factor declined gradually through the 50% range, before dropping into the forties for the first time in 2019, at 47.5%. It has continued to fall since, posting a new annual low of 42.1% in 2023. Through July this year, it is slightly below that level, at 41.5%.

The decline in coal’s capacity factor is noteworthy given it has occurred as the total amount of installed capacity has fallen: Coal plant operators are generating less with less capacity. Put differently, even the retirement of older, poorer performing plants in the past 15 years has not resulted in an increase in generation at the remaining plants, which are generally younger and should be more competitive. This decline is also economically problematic for coal plants because lower power production means the fixed costs of plant operation and maintenance—which usually rise as plants age—are spread over fewer megawatt-hours generated, raising the cost of that power.

The outlook is not going to improve, particularly as the rapid buildout of solar and battery storage, additional wind and gas continue to undercut coal's economic and technological viability. In fact, EIA’s latest Short-Term Energy Outlook expects coal's share of the generation market to fall close to 10% next April — little more than half the level of April 2021.

The U.S. is not moving as quickly as the United Kingdom, which last month closed its last coal-fired power plant after a roughly 12-year phaseout, but the endpoint is the same. Coal may retain a grip in U.S. politics, but its actual role in the generation system is shrinking annually. It is a trend we believe is irreversible