The hydrogen motives: Understanding the ‘why’ of the hydrogen push in Asia and beyond

Key Findings

Hydrogen appeals to many as an alternative source of energy, so it is important to understand country-level goals, but this needs to be complemented by recognition of the industry motives behind favoring the fuel.

Contexts vary widely: certain industries could have significant hydrogen potential, while for others it may present an unpromising and inefficient pathway.

Emerging Asian markets are likely tempted by the hydrogen pull from developed East Asian countries, but caution is warranted to avoid distracting themselves when other net-zero pathways are underexplored.

Various industry interests are at play behind clean energy drive

Interest in hydrogen is on the rise worldwide. In Asia, the use of hydrogen and its fuel derivatives, such as ammonia and methanol, is being promoted for novel applications such as transport and power generation because burning hydrogen releases no carbon dioxide. It is timely to outline the motivating factors and industries at play in the hydrogen space to understand a landscape also shared by renewable energy and electrification.

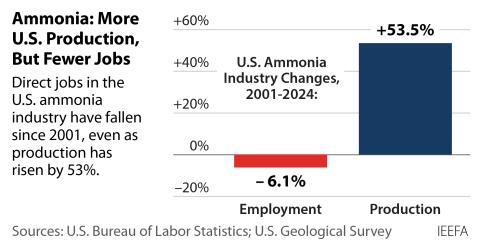

Clean hydrogen deployment will be instrumental in the pursuit of global net-zero emissions as not all sectors can easily switch to a renewable electricity path. The International Energy Agency has forecasted a potential need for more than 500 million tonnes annually by 2050. Current global consumption stands at about 100 million tonnes a year, mainly for fertilizers, oil refining and other industries using hydrogen that is practically all made from fossil fuels.

Skeptics are less optimistic about the growth of hydrogen, considering energy-inefficient supply chains, competing alternative pathways, and an apparent lack of enthusiasm around the world to clean up existing hydrogen uses before leaping into other applications. The contrasting views form a crucial juncture that calls attention to hydrogen’s potential for being oversold by industries trying to stay relevant.

It is not all rosy, because downsides may be seen in production, transport and costs. Clean hydrogen is still very expensive. It is created by two main methods: “green hydrogen” is produced with electrolysis using clean electricity, and “blue hydrogen” through the processing of fossil fuels combined with carbon capture, the latter of which is under scrutiny for its emission performance. Then, to move the manufactured hydrogen from its point of origin to usage, energy losses of 60%-70% are often encountered. Due to these drawbacks, some industries want to secure government support.

The energy importer’s motives. Notable progress can be observed in major energy importers such as Japan, which has exhibited leadership in bilateral and multilateral initiatives. The country has produced less than 14% of its energy needs over the past decade, in contrast with other industrial nations, which typically show stronger energy self-sufficiency, for instance, the United States with 106% and Australia, 345%, in 2020. It is therefore unsurprising that Japan is pursuing more importable commodities. In April, the country announced plans to quadruple its hydrogen target by investing US$107 billion in the hydrogen supply chain over the next 15 years. The substantial commitment built on Japan’s receipt in recent years of blue ammonia from Saudi Arabia and liquefied hydrogen made from Australian coal, both shipments being the world’s first. While the emission credentials of the cargoes will likely still invite questions, Japan’s pioneering efforts toward establishing a new global supply chain are evident and may tempt other Asian countries to jump on the bandwagon, as users or as exporters.

Elsewhere in Asia, the fuel has been gaining traction in major energy-importing countries. South Korea is home to the world’s largest fleet of hydrogen-powered cars. China is pursuing the establishment of electrolyzer manufacturing, although its near-term clean hydrogen target is modest. India is exploring green hydrogen, having an eye to reducing dependence on imported fuels and feedstocks leveraging its renewables expansion. Singapore, home to sizable refinery and petrochemical industries, is another country contemplating hydrogen.

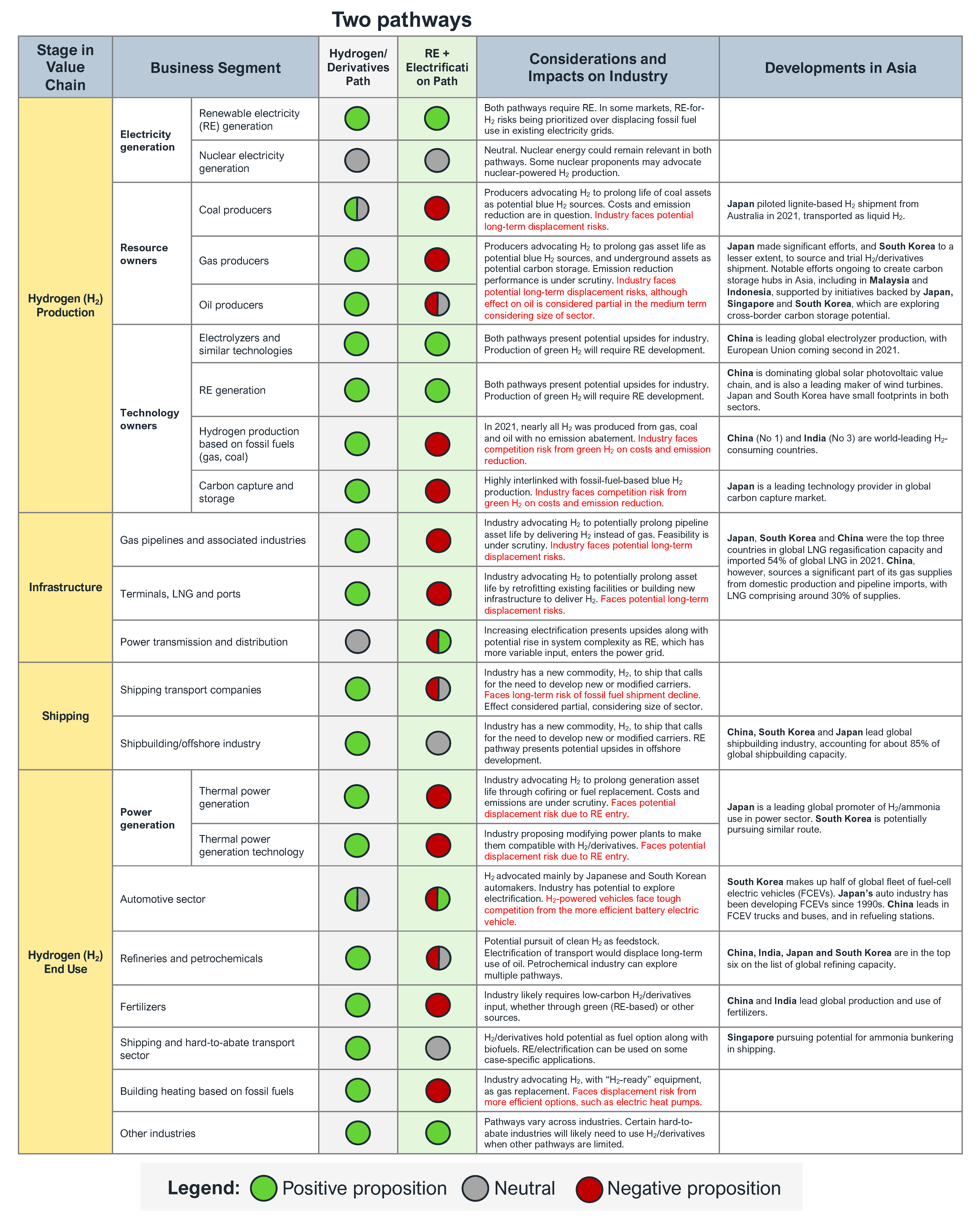

The industry motives. The hydrogen trend can be further illuminated by mapping industry interests to complement the country-level targets. Table 1 presents a simplification of dual paths that different sectors can take in pursuing net-zero goals. The first path outlines the adoption of hydrogen and its derivatives, while the second path describes clean energy and electrification. There are certainly other pathways with current and future technologies, but the table prioritizes simplicity to aid understanding.

By way of example, contrast shipping with the gas pipeline sector. Shorter shipping routes are expected to be electrified, but on the whole, vessel electrification will probably remain limited because battery life for long journeys could be challenging and will need to be complemented, such as by using the hydrogen-based methanol or ammonia. Both hydrogen-based fuels and biofuels hold prospects for the sector.

The gas pipeline sector has distinctly different considerations. In a future where the odds are on increased electrification, applications such as heating in buildings would likely tilt toward the more efficient electric-based options, such as the electric heat pump, straining the gas business. Under the scenario of tough competition, gas pipeline owners would probably fall back on existing infrastructure by proposing the repurposing of pipelines for transporting hydrogen instead, whether in full or as a partial blend with gas.

For stakeholders, a difficult exercise is to weed out which of the hydrogen promises are driven by a real pursuit of progress, and which ones in effect serve business interests vying for relevance amid a shifting landscape.

However, many are cautious about the technical limitations and safety challenges of using gas pipelines for hydrogen. Another concern is that a partial blend yields only a modest impact on emissions. A 20% hydrogen blend will raise gas prices while reducing CO2 emissions by only 6%-7%, a reason why in some markets, lobbying for government support is rising.

Hydrogen is a costly fuel, thus competition from alternative pathways will remain a challenge across all applications. Green hydrogen costs vary widely depending on its origin, ranging from US$4 to more than US$8/kg. It is comparable to the liquefied natural gas (LNG) range of US$30-US$60 per million British thermal units (MMBtu), three to six times Asian spot LNG prices in recent months. Around the world, various goals have been outlined to make hydrogen cheaper, particularly to reduce green hydrogen prices below blue hydrogen.

For stakeholders, a difficult exercise is to weed out which of the hydrogen promises are driven by a real pursuit of progress, and which ones in effect serve business interests vying for relevance – and buying time – amid a shifting landscape.

Suppose hydrogen meets its target price of US$1-US$2/kg in the next couple of decades and the export chain materializes. It will cost US$7-US$15/MMBtu plus significant transport charges. Japan is accustomed to importing LNG at US$10-US$13/MMBtu, but emerging Asian markets would be wise to tread carefully if they followed the Japanese’s footsteps to burn hydrogen. Countries with excellent renewable resources could be in a position to become hydrogen exporters but are unlikely consumers when other net-zero pathways remain underexplored.

Given the high costs, challenging supply chain and alternative pathways, competition is a reality even in the most promising applications of hydrogen. For stakeholders, a difficult exercise is to weed out which of the hydrogen promises are driven by a real pursuit of progress, and which ones in effect serve business interests vying for relevance – and buying time – amid a shifting landscape.

Many industries are facing a material risk of being displaced in the road to net-zero emissions. As policy support for hydrogen builds up and the market takes shape, it is important for stakeholders to understand the industry interests at play. For some sectors, hydrogen adoption could be credible because alternative net-zero pathways are limited, while for others, their foray into the fuel just does not hold water.