Australia’s steel sector too focused on replacing one fossil fuel with another

Key Findings

Australia will struggle to compete on cost with the Middle East on gas-based iron and steelmaking.

Producing iron and steel using gas is emissions-intensive. Trying to reduce emissions with carbon capture and storage (CCS) will only make the process more expensive.

CCS has a history of failure and ineffectiveness, and unlike green hydrogen-based iron it does not command a price premium in the market.

Despite having much cheaper gas, the Middle East is already starting to replace gas with green hydrogen for iron and steelmaking.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

Across much of the developed world, steel decarbonisation efforts are focused on how quickly fossil fuels can be replaced with renewable energy and green hydrogen. Australia’s steel sector is currently more focused on replacing one fossil fuel with another.

BlueScope Steel has been heavily intervening in the Australian gas market debate via media commentaries, advocacy campaigns, submissions, and most notably a recent National Press Club address. The company points out that, in order for it to stop using coal to make steel, its needs to see greater domestic gas supply at lower prices – below AU$10 per gigajoule (GJ).

BlueScope’s interventions are significant – not only does it operate one of Australia’s two blast furnace-based steel plants at Port Kembla in New South Wales (NSW), it is also part of a consortium considering the acquisition of the other one at Whyalla in South Australia (SA).

The technology currently in the most prominent position to replace coal-consuming blast furnaces is direct reduced iron (DRI). This is a mature technology operating at commercial scale in places like the Middle East and the US. DRI reduces iron ore into iron using methane gas (reformed into hydrogen and carbon monoxide) instead of metallurgical coal, but it can use 100% hydrogen.

Where green hydrogen is used, green iron and steel are produced. Despite world-wide setbacks to green hydrogen development, iron and steel remains one of the key sectors where it looks likely to play an important decarbonisation role.

Gas will play a temporary role in the steel technology transition away from coal while green hydrogen supply scales up. But there is a risk Australia will see gas-DRI locked in for decades, conceding the green iron and steel opportunity to places like Brazil, Canada and the Middle East.

Only a few months ago, IEEFA predicted that the steel technology transition would be used as an excuse to call for the opening up of new gas reserves in Australia. BlueScope has now called for “Accelerated development of new gas fields and infrastructure”. Meanwhile the Premier of SA – a state previously positioning itself as a global leader in truly green iron and steel – has voiced strong support for the accelerated opening of the Narrabri gas project in NSW, with one eye on gas supply to the Whyalla steel plant.

This is despite Narrabri gas having an expected production cost of almost A$10/GJ and a total cost delivered to Melbourne of up to A$12.62/GJ. Although the delivered cost to steel plants may vary, Narrabri gas seems very unlikely to help push east coast prices below the A$10/GJ benchmark BlueScope says it requires.

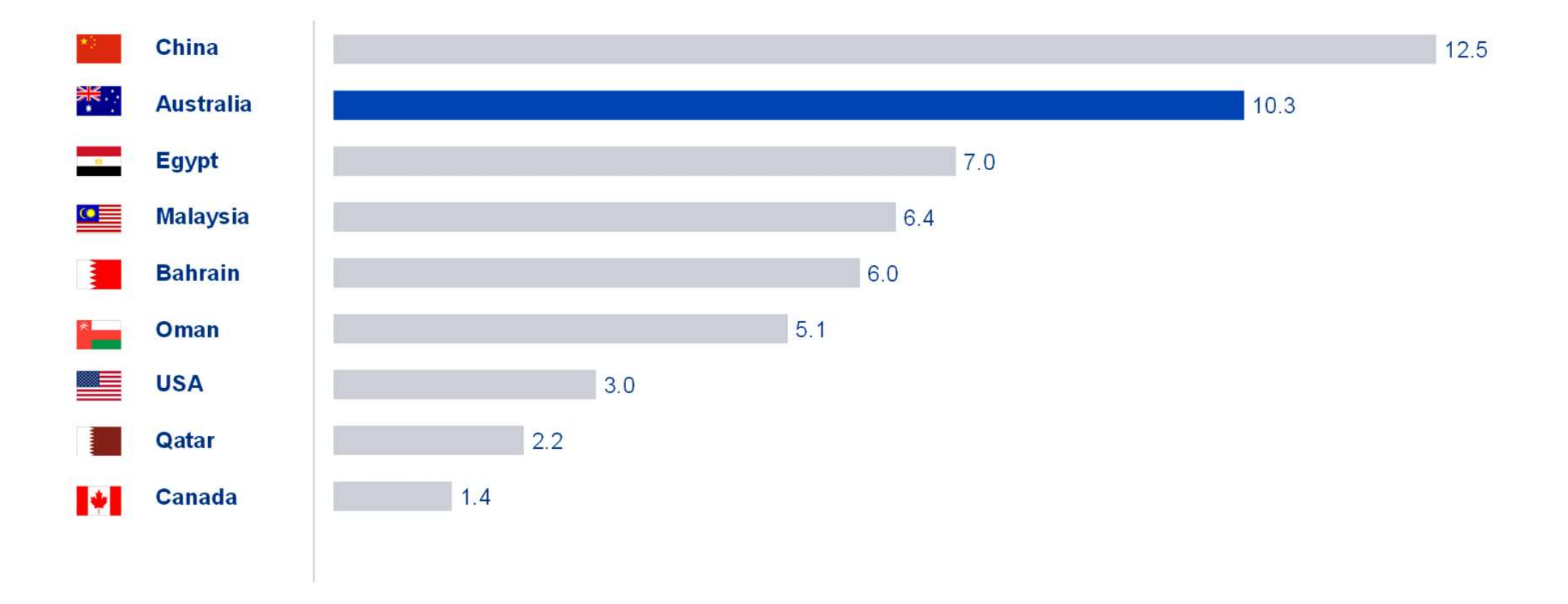

BlueScope is right to point out that high gas prices in the east coast market are an issue for the competitiveness of gas-DRI. In Oman, where new DRI projects are already under development, gas prices are half those encountered in Australia, according to data BlueScope supplied in its recent submission to the Gas Market Review (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Wholesale price comparisons, selected countries, 2024, AU$/GJ

Source: BlueScope, Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2025, IGU Wholesale Gas Price Survey 2025, EY-PS

Source: BlueScope, Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2025, IGU Wholesale Gas Price Survey 2025, EY-PS

Even if Australian east coast gas prices could get below BlueScope’s AU$10/GJ target, it’s hard to see how Australia will be competitive on gas-based iron and steelmaking with the Middle East, where DRI technology is already well established and new projects are underway. And the high emissions of gas-based iron and steel would require efforts to mitigate them, adding even more cost.

Gas-based steel has lower emissions than coal-based blast furnaces, but it remains emissions-intensive, at 1.4 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) per tonne of crude steel produced, according to the World Steel Association. You can’t make green iron and steel with gas.

Methane leaks released during gas production only add to this. Satellite monitoring is helping to increase attention on the issue of methane leaks and will intensify global efforts to control them. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) for iron and steelmaking would do nothing to address such methane leaks.

With its history of underperformance and failure, CCS is in no position to decarbonise gas-based steel. The world’s only commercial-scale CCS facility for steelmaking captures only around 25% of that plant’s Scope 1 and 2 emissions. The cost of CCS means this facility would likely never have been built if the captured CO2 wasn’t used for enhanced oil recovery, enabling the release of even more emissions.

The new Global Status of CCS report, published by the Global CCS Institute in October, shows no visible progress for iron and steel CCS at all. This is not surprising given Midrex – the key global supplier of DRI technology – recently said of CCS that “its practical use in steelmaking remains limited”, and that “Despite being promoted as a decarbonization tool for heavy industry, CCS has delivered limited success in practice.”

The location of CO2 storage is also a huge barrier to CCS for iron and steel in Australia. Infrastructure SA released a report in 2025 suggesting that carbon capture at Whyalla could be the foundation for a wider CCS ecosystem in SA. This would involve building a CO2 pipeline to transport captured carbon hundreds of kilometres from Whyalla to the Moomba CCS facility, at significant additional cost.

The cost and emissions of gas-based DRI become even more of an issue if Australia goes beyond just replacing its blast furnaces with DRI and starts developing a fleet of additional DRI plants to process its iron ore into iron for export.

The only effective way to decarbonise DRI-based steelmaking is to replace gas with green hydrogen. Unlike gas, Australia can be globally cost-competitive on green hydrogen.

In addition, there are opportunities to secure off-takers of truly green iron and steel – at a price premium – to support early use of green hydrogen-based DRI. The cost of steel for some consumers (most prominently carmakers) makes up only a very small proportion of the total cost of their product. This is the approach Stegra has taken, allowing it to begin constructing a 100% green hydrogen, DRI-based steel plant in Sweden that will begin operations next year.

Meanwhile, despite having much cheaper gas than Australia, Oman is now turning towards green hydrogen with early use required for new DRI projects. Meranti Green Steel’s planned DRI plant in Oman intends to start on a mix of 15% green hydrogen and 85% gas before progressively ramping up green hydrogen use as it becomes available.

This puts Oman’s DRI plans on a credible pathway towards truly green iron and steel that sets a benchmark for Australia. Oman’s DRI developments are more advanced than Australia’s, and its focus on early green hydrogen use makes it a leader in global iron and steel decarbonisation – leaving Australia trailing.

Rather than new gas field developments that won’t give the steel sector what it needs to shift away from coal, Australia should be targeting early green hydrogen use for DRI. This would reduce the demand for gas at future Australian DRI plants and put them on a realistic decarbonisation pathway.