Steel CCUS update: Carbon capture technology looks ever less convincing

Download Briefing Note

View Press Release

Key Findings

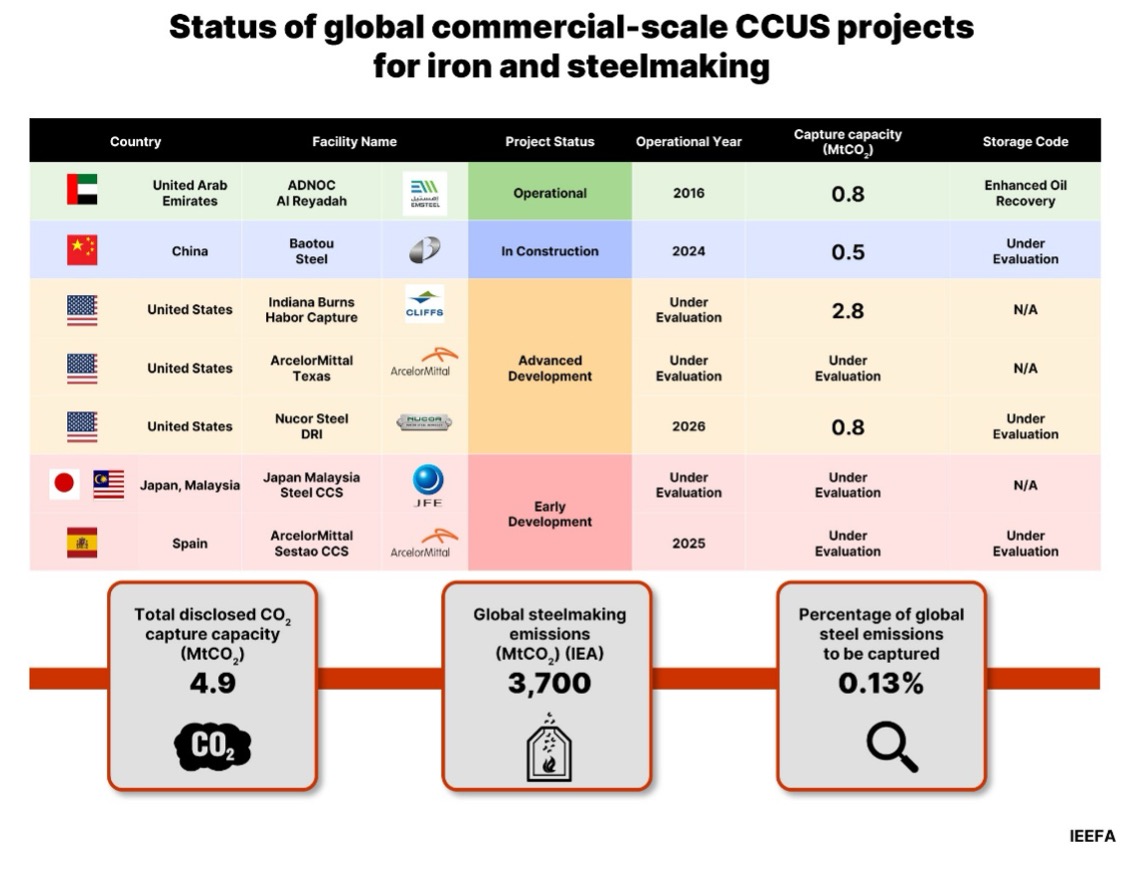

Six commercial-scale carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) projects for iron and steelmaking are in the development pipeline, up from three in 2023. However, the lack of available detail casts doubts over their development status and timelines.

The Al Reyadah project in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is still the world’s only operational commercial-scale CCUS project for steelmaking. It captured only 26.6% of the gas-based steel plant’s emissions in 2023. There are still no commercial-scale CCUS plants for blast furnace-based steelmaking in operation anywhere in the world.

Since IEEFA’s April 2024 report on steel CCUS, carbon capture projects have continued to fail and underperform in other sectors. Equinor recently admitted over-reporting the performance of its flagship Sleipner CCUS project for years due to faulty monitoring equipment.

Despite mounting evidence to the contrary, major steelmakers and miners such as Nippon Steel, ArcelorMittal and BHP continue to insist to their investors that CCUS will play an important role in meeting their decarbonisation targets.

Hailed as the solution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions from steelmaking, the prospects for carbon capture and storage (CCUS) in the steel industry look increasingly bleak.

Major steelmakers and iron ore miners such as Nippon Steel, ArcelorMittal and BHP continue to insist to their investors that the flawed technology will play a significant role in meeting their decarbonisation targets despite growing evidence to the contrary. Behind the hype, however, the reality is few if any of these projects will likely enter operation.

CCUS is predisposed to major financial, technological and environmental risks. Low capture rates remain a key ongoing issue that is often underappreciated. The amount of carbon targeted for capture at a project tends to be significantly below its overall emissions. Furthermore, CCUS projects consistently struggle to meet even these low capture targets.

For example, the world’s only operational commercial-scale CCUS plant for steelmaking is the Al Reyadah project in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In 2023, it captured only 26.6% of the gas-based steel plant’s emissions, which are then used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

IEEFA highlighted the poor global track record of CCS projects across all sectors in its report Carbon Capture for Steel? Since the report was released in April, the technology has suffered further setbacks. A C$2.4 billion CCUS proposal for power generation near Edmonton, Canada, was cancelled in May on the grounds it was not financially viable. Meanwhile revelations have emerged that the flagship Sleipner CCUS project off Norway had been grossly over-reporting its carbon capture rates for years due to faulty monitoring equipment. Often cited as proof of CCUS’s technical feasibility, the Sleipner project further highlights the risks of attempting to implement CCUS at scale around the world.

Of the six CCS projects in the global pipeline according to the Global CCS Institute, fundamental details remain undisclosed, unknown or “under evaluation”, casting doubt over their prospects (see table below). Should any reach completion, they face a host of technical, financial and site-specific challenges.

Despite 50 years of attempts, the cost of CCUS remains stubbornly high. Innovative steelmakers are looking elsewhere to reduce their emissions, moving away from coal-based production to direct reduce iron (DRI) steelmaking, a mature, proven technology that can run on green hydrogen.

A major obstacle is that coal-burning blast furnace steel plants require multiple points of carbon capture to allow production of low-carbon steel, increasing the costs significantly. There are still no commercial-scale CCUS plants for blast furnace-based steelmaking in operation anywhere in the world. The cost involved means capturing sufficient carbon at coal-based steelmaking sites will likely never be financially viable.

Virtually all steelmakers planning or constructing commercial-scale low-carbon steelmaking capacity have turned to hydrogen-based or hydrogen-ready DRI plants, not CCUS. The 2030 project pipeline capacity of DRI plants has reached 96 million tonnes a year (Mtpa) while commercial-scale CCUS for blast furnace-based operations remains stuck on just 1Mtpa.

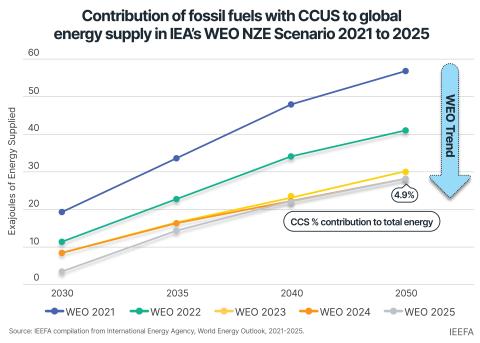

The cost of green hydrogen – a key enabler of truly low-carbon iron and steel production – is also high but has a much better chance of declining through economies of scale and renewables cost reduction. CCUS for blast furnace-based steelmaking is being left behind by a better alternative that can outcompete it on both cost and emissions reductions.