The Asia Pacific renewable supply chain opportunity

Download Full Report

View Press Release

Key Findings

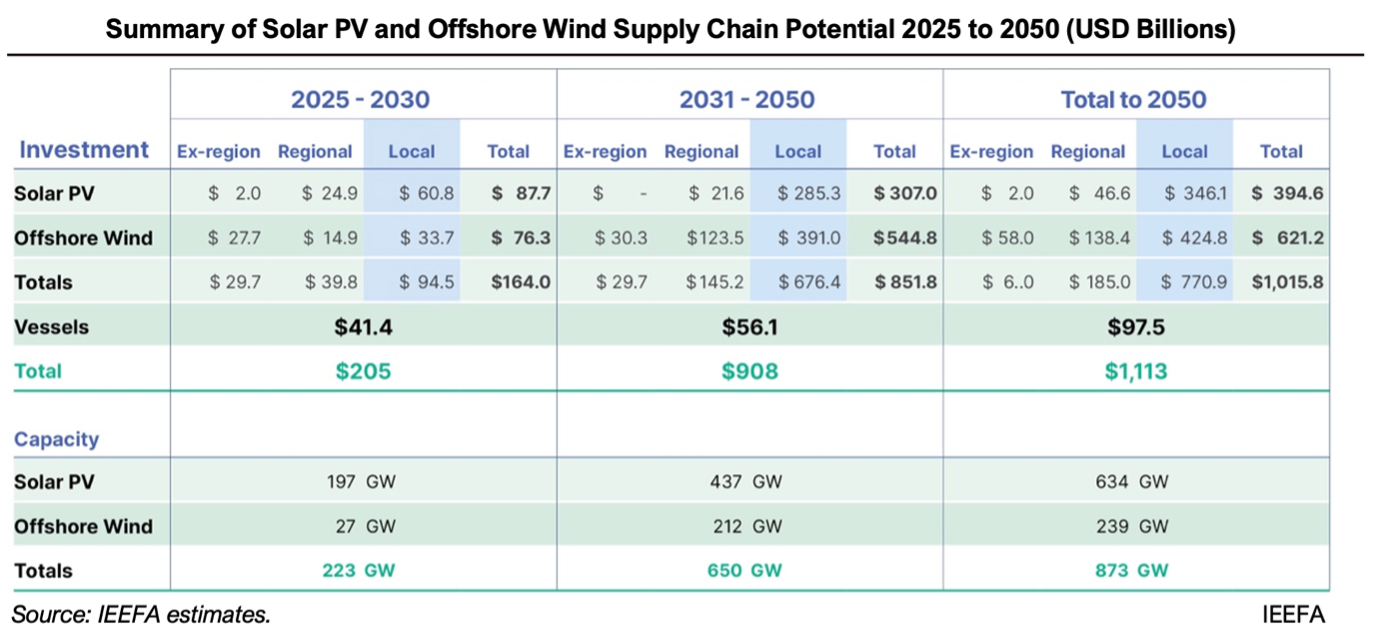

The potential for solar photovoltaic (PV) and offshore wind supply chain investments in Asia Pacific presents a US$1.1 trillion opportunity to 2050, of which 75% would be spent on and remain within the countries undertaking these projects.

Solar PV power projects represent the “here and now” opportunity to capitalize on the supply chain, with US$346 billion of potential localized inputs out of US$395 billion of investment through 2050.

Offshore wind is a core growth sector in the Asia Pacific, with US$425 billion of localization potential on US$621 billion of total investment, and shipbuilding opportunities of up to $97 billion to 2050.

Governments looking to tap into the clean energy supply chain need to look beyond panels and turbines. Balance of systems for solar and offshore wind represent 75% and 68%, respectively, of total spend on projects. That is where the greatest business opportunity is for domestic suppliers, manufacturers, and contractors, starting now and running over the next 25 years.

Executive Summary

The Asia Pacific region possesses vast, untapped potential for renewable energy, particularly in solar and wind resources. Harnessing this potential could transform the region’s energy economy. There are gigawatts of projects looking for investment with development activities stretching over decades. This sustained regional investment opportunity could potentially drive the development of regional and domestic renewable energy supply chains as core businesses.

This report focuses on two energy transition sectors: solar photovoltaic (PV) projects and offshore wind farms.

Solar PV offers the “here-and-now” opportunity – it already represents the lowest marginal cost of electricity generation globally, with overall prices continuing to decline. This creates an immediate opportunity for governments to achieve dual targets of decarbonizing their grids while providing their consumers with the lowest cost of power.

Offshore wind offers the potential for reliable, predictable, large-scale renewable energy supply. While currently nascent in the Asia Pacific, it represents a promising evolving opportunity over the coming years. Global evidence shows offshore wind rapidly declining in costs with larger scale implementation. Further, wind can complement solar generation, as wind typically produces the most power at night.

Together, solar and offshore wind could significantly contribute to regional energy transition efforts, creating substantial large-scale economic opportunities.

Investments could reach hundreds of billions of dollars over the next twenty-five years, with a large proportion of those capital flows supporting domestic manufacturing, supply, and service sectors. Governments across the region are already contemplating how to capture that value and keep it onshore.

Policymakers, when considering solar and wind energy supply chains, often focus on the most symbolic components of generation facilities: solar PV panels and wind turbines. They are the most visible and seemingly obvious focus for “green technology” investment.

While these are attractive symbols of the sustainable energy transition, the supply chain for solar and wind energy extends far beyond these components. It includes materials, fabrications, infrastructure, logistics, and services that are needed to deliver fully functioning energy projects. These inputs can provide great value to the domestic economy over decades.

Some of these elements are advanced green technology in themselves, while others are more commonplace materials and services. All are essential and some inputs can be equally or even more valuable than the technology they support. Understanding their scope and value is essential to maximizing the renewable energy opportunity.

Beyond solar PV modules, the solar energy supply chain comprises numerous components such as electrical equipment, racking and tracking systems, controls, construction contracting, testing, and operations services.

Offshore wind requires fabricating out of raw steel foundations and towers, creating forgings and fittings, constructing transmission substations, and laying undersea cables between them. These components and fabrications must be lifted, shipped, and installed, requiring fleets of ocean-going vessels equipped with some of the world’s largest marine lifting and portside equipment. Additionally, robust port facilities and manufacturing shops are required to support these operations. All of these are supply chain components that complement wind turbines.

When developing national renewable energy technology strategies, countries would benefit from looking beyond panels and turbines. These high-tech components, although crucial, require significant investments, face high competition and low margins.

When plotting national renewable energy technology strategies, countries would benefit from looking beyond panels and turbines.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the Chinese solar supply chain, where China dominates the process of converting raw silica into PV modules. The country produces 83% of the world’s polysilicon, 97% of wafers, 83% of cells, and 72% of modules. Additionally, China has over 100% excess manufacturing capacity, sufficient to supply double the projected global demand into the next decade.

For countries attempting to break into the PV market, China’s dominance is an extreme challenge. Currently, markets looking to compete with China are producing outputs that are anywhere from 20% to 200% more expensive; meanwhile, China’s costs are further dropping while those of other countries are remaining stagnant or are rising.

In contrast, the non-panel, non-turbine supply chain, offers more opportunities. Many of these “balance of system,” or BoS, components and services are best provided locally and represent the majority of investment costs in a solar PV project or wind farm.

In solar PV, BoS components account for 60% to 72% of total investment, while in offshore wind farms, they represent about 58% to 68%. These localized costs are typically shared amongst manufacturers, suppliers and service providers, instead of going to a single company. This creates the potential for broader distribution of economic benefits.

Size of the Opportunity

The order-of-magnitude assessments undertaken for this report estimate that from 2025 to 2050, the Asia Pacific region has a combined investment potential of US$1.1 trillion in solar PV and offshore wind energy, creating a potential 873 gigawatts (GW) of clean energy. Of that, US$394 billion supports solar PV projects totaling 634 GW and US$621 billion helps construct 239 GW of offshore wind farms.

Local supply chain development represents the bulk of this opportunity. Over the period 2025 to 2050, 72% of solar PV investment (US$346 billion) and 68% of offshore wind investment (US$425 billion) are projected to use local materials, manufacturing, and service providers. In the offshore wind sector, which uses fleets of installation, construction and maintenance vessels, another US$72 to US$97 billion for new fleet construction to 2050 may be required. This will be a boon to regional shipbuilders and to the maritime economies that support and maintain these fleets.

The estimates in this report are based on nationally announced plans for renewable energy capacity additions over the period to 2030 and onward to 2050. There are varying degrees of policy support and market readiness for implementation. Projects already underway within national frameworks were counted toward near-term 2030 goals. Where programs have yet to be implemented, practical assumptions about timing toward first implementation were made, pushing start dates out. By 2050, it is assumed that these plans will be achieved.

National plans vary, with some being ambitious and others conservative. Collectively, these differences balance out, making the aggregate figures reflect a more average attainment. With continued cost drops and increased experience, there is potential for these plans to evolve.

For example, Indonesia has very modest short-term additions in solar, while Japan has very ambitious goals. Taiwan is already implementing its offshore wind program, whereas other countries are either at a very small scale or yet to begin. Yet all countries in the region can benefit from empirical evidence from their neighbors on what works, what does not, and the associated costs. Offshore wind, in particular, benefits from a regional supply chain sourcing strategy in its early implementation stages. Eventually, some of those components and systems may be better produced locally, but in the meantime, the supply chain can learn and mature.

Taken together, solar PV in the near term and offshore wind in the medium to long term are tremendous growth businesses. The supply chain inputs to solar and wind projects in the Asia Pacific through 2050 are estimated to be worth US$185 billion regionally and US$770 billion in potential localized national sourcing. Additionally, another US$72 billion to US$97 billion needs to be invested in marine vessels to support offshore wind.

These estimates are based on current government policies on targeted capacity additions and current studies using supply chain cost trajectories. If overall lifecycle costs further decrease as predicted, these forms of energy will become even more economically advantageous. With the potential to grow localized solar and wind supply chain content over time, there is a strong incentive for governments and businesses to pursue these industries.