IEEFA U.S.: Two of Duke Energy’s plants in North Carolina reflect national trend in baseload slippage for coal

Plant closures grab most of the U.S. coal industry headlines lately, but an equally important story emerging from the data illustrates another facet of change sweeping the utility industry and its suppliers: Coal is losing its foothold as a baseload power resource.

This shift is occurring nationally, but what’s happening in North Carolina is a good snapshot of the larger decline in coal’s importance to electric utilities.

Duke Energy, which has four million electricity customers in North and South Carolina through two operating units, Duke Energy Carolinas and Duke Energy Progress, is rapidly transitioning away from coal. It has closed roughly 3,000 megawatts of coal-fired generating capacity just since 2010 while building new combined cycle natural gas plants and, increasingly, utility-scale solar photovoltaic installations.

What’s especially interesting in Duke’s case is how it is using some of its remaining coal plants now. While coal has long been considered a baseload generation resource, and while its proponents—which include the current administration—have relied on this distinction as a sort of crutch, Duke is using many of its coal plants not as baseload generation but as backup for when other, cheaper resources can’t quite meet the system’s needs.

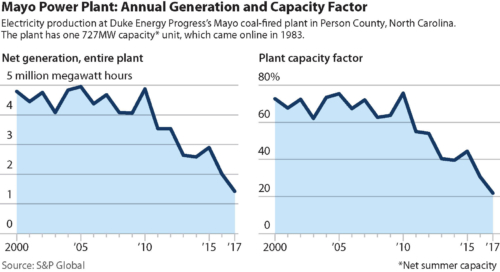

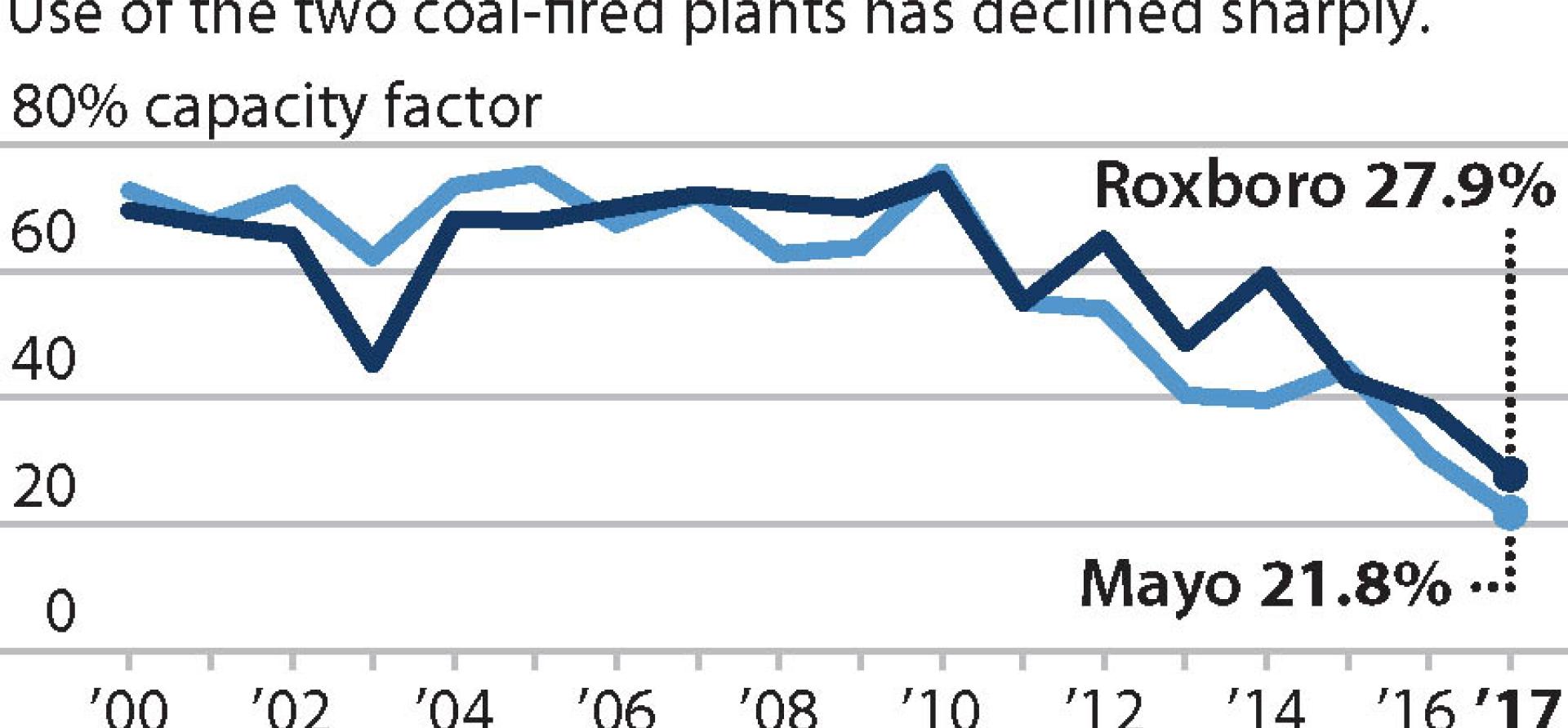

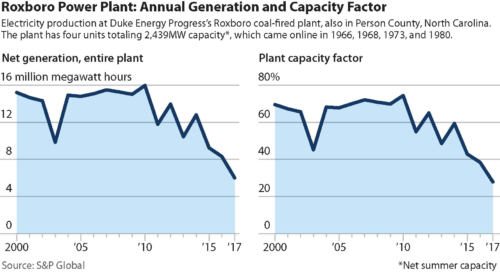

This can be seen at two of the company’s larger still-operating coal-fired generators: the single-unit, 727-megawatt Mayo Plant and the four-unit, 2,439MW Roxboro Plant.

Those two plants essentially ran flat-out from 2000-2010, posting capacity factors of 69.5 percent and 67.3 percent, respectively, over the course of that decade. But that began changing in 2011, and the decline since then has been nothing short of extraordinary, as the graphics below indicate.

According to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence, the Mayo plant’s capacity factor in 2017 was 21.8 percent, and it never operated at more than 50 percent, with July being the peak month, at 47.7 percent. The Roxboro’s plant did only slightly better, posting a capacity factor of 27.8 percent for the year. Importantly, Roxbury operated at less than 20 percent of its capacity for six months in 2017.

According to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence, the Mayo plant’s capacity factor in 2017 was 21.8 percent, and it never operated at more than 50 percent, with July being the peak month, at 47.7 percent. The Roxboro’s plant did only slightly better, posting a capacity factor of 27.8 percent for the year. Importantly, Roxbury operated at less than 20 percent of its capacity for six months in 2017.

Clearly, neither of the plants can be considered baseload units anymore.

Mayo’s performance has improved only slightly this year; the plant has operated at 29 percent of its capacity. Roxboro has operated at about the same level as last year, posting a capacity factor of 27.4 percent during the first seven months of 2018, although for four months in a row this spring it operated at less than 20 percent.

Increasingly, these plants are used only during the hottest days of summer and the coldest days in the winter.

While Duke does not publicly talk about the transition away from coal, the utility has acknowledged the change afoot in its annual integrated resource planning (IRP) documents. Up until 2016, Duke officially designated the two plants baseload facilities; starting with its 2016 IRP, the utility changed the their status to intermediate load resources.

THE BIGGER QUESTION IS HOW LONG THESE NEWLY CLASSIFIED PLANTS will continue to be economic for Duke to keep online.

Another indicator of the growing obsolescence of both plants can be seen in coal deliveries. In 2010, Roxboro had 5.92 million tons of coal delivered; in 2017 that figure was 2.43 million tons. In 2010, Mayo had 1.71 million tons of coal delivered; in 2017 it was down to 545,000 tons. Coal for both plants comes from mines in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky.

The company’s current plans call for retiring Roxboro in 2028, but nothing about that date is sacrosanct. As Duke noted in its latest IRP, the date is merely an indicator of when the plant, whose last unit entered commercial service in 1980, will be fully depreciated—for accounting purposes. It is not an indicator of anticipated need. In its 2014 IRP, Duke pegged the plant’s retirement date at 2032.

How long can increasingly marginal power stations be justified?

The same can be said of Mayo, which entered commercial service in 1983 and is not officially scheduled to close until 2035.

The plants’ operating costs suggest that both retirement dates may be accelerated.

The average grid load in 2017 in the Duke Progress planning area, where both plants are located, was 7,500MW. According to S&P, the company has roughly 8,000MW of capacity at variable O&M costs of $34.50 per megawatt-hour (MWh) or less.

Both Roxboro and Mayo cost more than that to run—meaning that on an average day neither plant may be called upon for electricity

Roxboro 3 comes close to the average (at $34.57/MWh), but its other three units do not. Mayo, although it is newer, produces electricity at $40.72/MWh.

Production costs will be a particular problem at the Mayo plant. Peak demand in the Duke Progress area topped 12,000MW only 26 days in 2017, according to S&P data. The utility has a rough total of 12,000MW of generating capacity with power production costs below Mayo’s.

To further weaken the outlook for Mayo and Roxbury, a host of new utility-scale solar is coming to North Carolina. As recently as 2011, the state had essentially zero installed solar capacity, but according to data from the Solar Energy Industries Association North Carolina now has 4,490MW of installed solar capacity (1,243MW of which was installed in 2017).

SEIA projects the solar total in North Carolina to roughly double, by an additional 4,230MW, over the next five years.

ALL OF THAT NO-FUEL-COST CAPACITY WILL PUSH BOTH ROXBORO AND MAYO MUCH FURTHER DOWN THE DISPATCH LIST, worsening their already anemic capacity factors and almost certainly hastening their retirements.

Beyond its plans for more solar, Duke just this month announced intentions to install an estimated 300MW of battery storage in North and South Carolina over the next 15 years, a significant increase over the roughly 15MW currently installed. Given that one of the most promising uses of such storage is to support renewable generation, this investment will only further undercut the need for the aging and costly Roxboro and Mayo plants.

While Duke has said it will end its use of coal generation in the Carolinas, it hasn’t been very ambitious about when full phaseout will actually occur. However, the data show clearly that transition is coming faster than almost anyone thought it would.

Dennis Wamsted is an IEEFA editor. He can be reached at [email protected]. IEEFA data analyst Seth Feaster contributed to this report. He can be reached at [email protected].

Related items:

IEEFA report: U.S. likely to end 2018 with record decline in coal-fired capacity

IEEFA update: Another Texas coal-plant closing, another market signal

IEEFA update: Unmistakable trends in American wind and solar