Why India’s carbon market needs a price stability mechanism

Key Findings

With its CCTS set to begin compliance in 2026, India has an opportunity to learn from international experience and embed market stability mechanisms, avoiding the costly corrections that have challenged compliance carbon markets worldwide.

Indefinite banking, though designed to offer flexibility and cost management, can create large credit surpluses under modest early targets, weakening carbon prices. Global experience shows that markets without early stability mechanisms face prolonged periods of ineffective price discovery.

A Price or Supply Adjustment Mechanism (PSAM) is a transparent, rule-based framework that adjusts credit supply when the market shows imbalance from oversupply or scarcity. It is a safeguard for when reality diverges from plan. By making predictable adjustments, a PSAM preserves scarcity, anchors expectations, and avoids ad hoc interventions.

What is India’s CCTS?

India has taken a pivotal step with the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme (CCTS), creating a national carbon market that puts a price on emissions across industrial sectors. Carbon markets work by moving pollution from an unpriced externality into day-to-day decisions, so efficiency upgrades, cleaner fuels, and low-carbon technologies become financial investments. A credible, sustained carbon price can steer a fast-growing economy towards a competitive low-carbon path.

With its CCTS set to begin compliance in 2026, India has an opportunity to learn from international experience and embed market stability mechanisms, avoiding the costly corrections that have challenged compliance carbon markets worldwide.

Navigating growth and climate goals

India has opted for a baseline-and-credit system with an intensity-based carbon market to balance climate goals with economic growth. These systems are well suited to early-stage decarbonisation, when regulators are still developing abatement cost estimates, sectoral benchmarks, and an emissions data repository. By targeting emissions per output unit, they avoid penalising economic expansion while promoting industrial modernisation.

This approach requires careful calibration as credit supply depends on actual output and performance, making benchmark setting critical for market balance. Initial emissions intensity targets will translate to a modest 3% reduction on average across sectors, reflecting the importance of complementary stability mechanisms.

Design vulnerabilities can undermine market credibility

Certain well-intentioned features of India’s CCTS, like indefinite banking, may affect market stability. Banking, a valuable flexibility tool, lets companies manage compliance costs over time and rewards early action. Yet, when combined with modest early targets, large surpluses can build up, meeting future compliance obligations without requiring new investment and dampening prices. These targets reflect practical uncertainties rather than weak ambition, as regulators prioritise smooth market entry and manageable compliance costs.

International experience demonstrates that markets which embedded stability mechanisms early versus those that incorporated them later experienced a long period of ineffective price discovery. California’s cap-and-trade system exemplifies proactive design benefits. Launched in 2013, with comprehensive stability measures, a rising price floor (initially US$10, increasing by 5% plus inflation annually) and an Allowance Price Containment Reserve, California has maintained consistently stronger price signals than other carbon markets.

Other baseline-and-credit, intensity-based systems comparable to India’s CCTS have faced similar challenges. Alberta’s TIER system accumulated more than 53 million surplus credits by 2023, with market prices falling 40% below the official price, while Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism required comprehensive reforms in 2023 to establish meaningful price signals after seven years. The EU’s ETS operated for 14 years before implementing its Market Stability Reserve (MSR), with carbon prices between €3 and €7 per tonne. Research by Climate Strategies suggests that nearly two-thirds of efficiency losses could have been avoided with earlier market adjustments.

PSAM serves as a stability mechanism

A Price or Supply Adjustment Mechanism (PSAM) is a transparent, rule-based framework that adjusts credit supply when the market shows persistent imbalance from oversupply or scarcity. It is not a substitute for getting targets right at the source, but a safeguard for when reality diverges from plan. By making predictable adjustments, a PSAM preserves scarcity, anchors expectations, and avoids ad hoc interventions. Like the EU’s MSR, which automatically adjusts auction volumes to counter surpluses and shortages, a PSAM would give India’s CCTS a built-in stabiliser. However, replicating the EU’s MSR is infeasible because CCTS credits are issued post verification, without an auction system for dynamic supply adjustment.

India’s CCTS already includes a price collar, an indicative floor and ceiling to dampen extreme price swings. However, it alone cannot clear a surplus and may keep prices artificially above the floor. Ideally, balance would come from strong benchmarks and sound banking rules. But perfect calibration is rarely possible.

A PSAM gives regulators and industries a pre-defined framework to adjust supply in line with actual market conditions. For India’s CCTS, a tailored PSAM could integrate three mutually reinforcing elements:

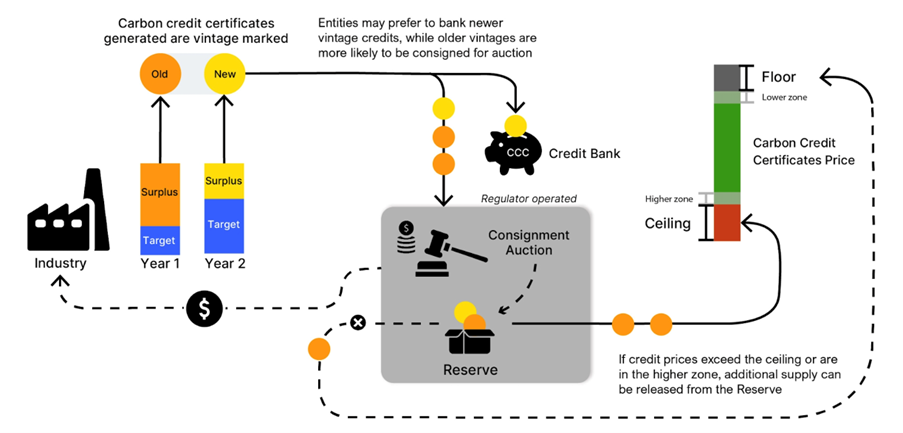

- Consignment auctions: Establishing a central, transparent platform for consignment sales, where a portion of earned credits is placed in a regulator-managed auction, creating a direct “control panel” to adjust supply. The auction decides how many credits enter the market, with the process also serving as a mechanism to build a market reserve when bids fall short of the reserve price. This could lay the groundwork for a smooth transition to broader auction-based allocation and responsive market governance.

- Vintage-based credit rules: Tag credits by issuance year and limit their compliance life within a rolling window, allowing regulators to tighten or relax eligibility for older vintages when surpluses build. A visible vintage price curve, with older vintages trading at a discount, signals expectations of tighter future scarcity, which nudges earlier use and improves investment planning.

- Price corridors: Retain and refine the price collar to guide intervention without rigid controls, using activation zones near the floor or ceiling instead of waiting for exact breaches. When prices approach the lower bound, fewer credits enter the market; near the upper bound, reserve credits are released.

These tools allow regulators to manage the market proactively without altering its core design or introducing costly fiscal interventions.

Why timely intervention is important

Embedding a tailored PSAM would guard against structural oversupply when initial benchmarks are set cautiously to ease market entry. It would reduce the risk of politically contentious “super-tightening” later to clear surpluses and signal that the market will deliver credible, durable price signals. India’s CCTS lacks a dedicated pilot phase – a feature of many ETSs that allows early market imperfections to be addressed before full-scale operations – making stability mechanisms even more critical.

A well-functioning CCTS can strengthen industrial competitiveness, align with global trade measures like the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism, and position India as a leader among emerging economies in carbon market design.

For the CCTS to move beyond an administrative framework and become an investment-grade instrument for the energy transition, its architecture must balance flexibility with discipline. A well-calibrated PSAM can provide that discipline, ensuring the market’s promise is realised in practice: a credible carbon price that drives sustained decarbonisation.

This article was first published by WEF.