Streamlining Bangladesh’s power sector to lessen overcapacity and financial burden

Key Findings

Bangladesh should limit its power capacity expansion spree, laying the foundation for minimising capacity payments and selecting the least-cost route.

A gradual promotion of renewable energy through a competitive process will be beneficial.

Strong policy measures will also be required to surmount the barriers affecting the country’s renewable energy promotion.

Bangladesh finally approved the long-awaited Integrated Energy and Power Master Plan (IEPMP) in November 2023, aiming to provide the impetus for the country’s energy and power sector development through 2050. While having a long-term plan provides policy certainty, the IEPMP appears to subordinate some key points, for example, overcapacity, the role of renewable energy and risks of unproven/expensive technologies/fuel.

The latest annual report of the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB) illustrates that its development plan already diverges from the IEPMP’s short-term demand projection. Also, the IEPMP’s assumption that renewable energy, such as solar and wind, is intermittent and requires additional reserve margin, which will only increase the power system’s overcapacity and inefficiency. Similarly, the application of different unproven and/or under-performing technologies and costly fuel in the mid- to long-term may further deteriorate the rapidly worsening financial health of the power sector.

As the IEPMP is a living document, it can incorporate changes in the coming years based on relevance and the country’s needs.

Power system overcapacity will continue in the short-term

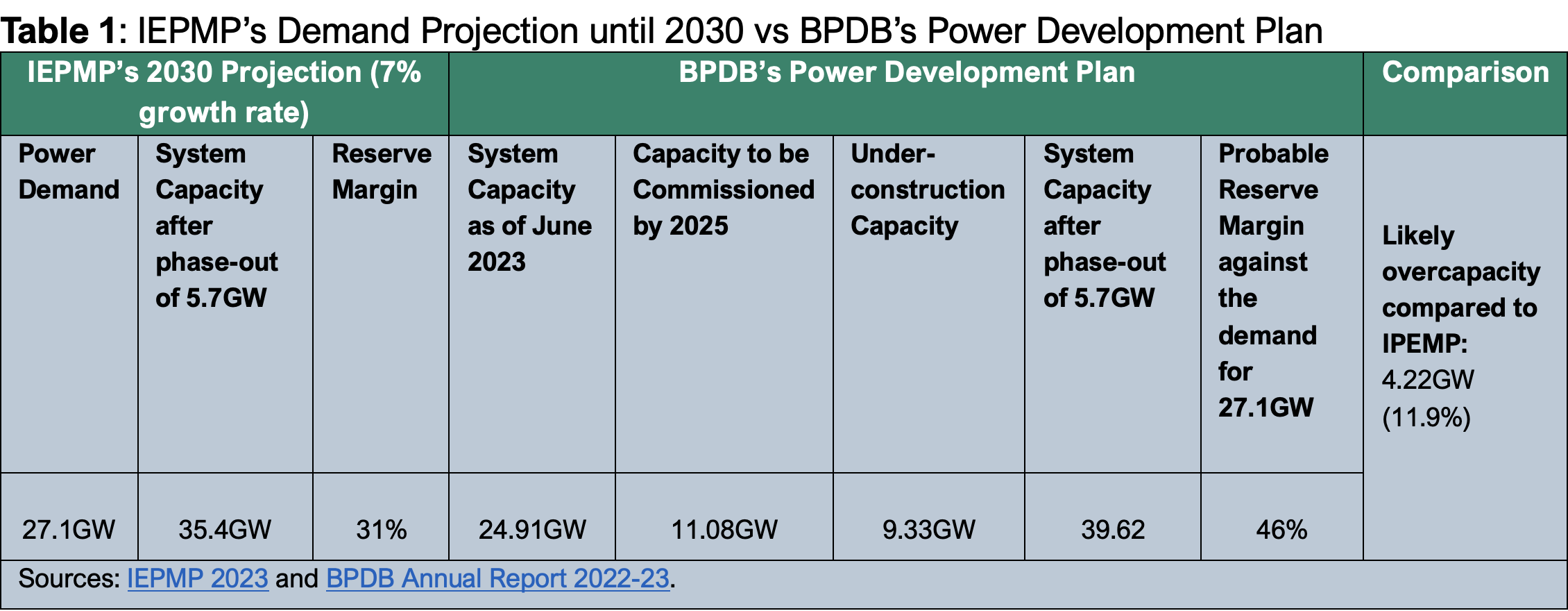

The IEPMP has projected that the country’s peak power demand will reach 27.1 gigawatts (GW) in 2030, following a 7% growth per annum. To meet this demand, IEPMP estimates the need for an installed power capacity of 35.4GW, including a 31% reserve margin.

However, based on the BPDB’s latest annual report, under-construction plants and those awaiting commissioning will result in a combined installed capacity of 45.32GW before 2030 (see Table 1). Even after phasing out old power plants of 5.7GW capacity, the installed capacity will exceed IEPMP’s estimate by 4.22GW. As such, the reserve margin will rise to 46%, much higher than the IEPMP’s consideration. Projects under the tendering and contracting stages, if commissioned before 2030, will increase the reserve margin further.

The system overcapacity has become a badge of inefficiency rather than prudence, affecting the financial health of the country’s power sector. As the sector grapples with a huge subsidy burden and capacity payments, streamlining BPDB’s development plan by downgrading high installed capacity to a realistic level seems ideal. Besides, there is no pressure to rapidly expand the system capacity when the maximum demand recorded last summer was 16.22GW against the current installed capacity of 25.93GW, excluding renewable energy and captive systems. Likewise, the maximum demand in December 2023 was only 10.92GW.

Additional reserve margin to accommodate renewable energy needs to be revisited

The IEPMP has concluded that the maximum peak power demand would reach 70.5GW in 2050, leading to a system capacity of 84.6GW for a 20% reserve margin (under demand growth scenarios: 7% until 2030, 5.8% until 2041 and 3.8% until 2050). The IEPMP assumed that the power system might have 26.2GW of renewable energy capacity in 2050 beyond the installed capacity, grounded on the premise that solar and wind are variable energy and incapable of serving energy during the evening. Hence, this 26.2GW renewable energy capacity over the installed capacity of 84.6GW will raise the system size to a mammoth 110.8GW.

The hypothesis appears untenable because of a couple of reasons. The cost of battery storage will likely fall significantly in the coming decades, making solar energy with a storage facility of two to three hours for evening application in Bangladesh more affordable. The country can realistically consider the role of battery storage after 2030 to meet part of its evening peak demand. Even now, solar power with battery backup for a couple of hours will be cheaper than the energy generated in some power plants at a cost of over Bangladeshi Taka (Tk) 40/kilowatt-hours (kWh) (US$0.36/kWh) during the fiscal year 2022-23.

Additionally, wind is a more stable energy compared to solar and will deliver energy during both day and night. Coastal areas, which are suitable for wind power as different studies substantiate, experience more wind speed in the evening. Contrary to the IEPMP’s view, wind can also be a source of power during the night.

Thus, setting up a renewable energy capacity of 26.2GW beyond the installed capacity of 84.6GW will increase inefficiency, overcapacity and system cost. Instead, the system size should be downgraded, keeping confidence in renewable energy.

Unproven and expensive technologies/fuels may deepen risks

The IEPMP foresees prominent roles of carbon capture and storage (CCS), ammonia co-firing and hydrogen in Bangladesh’s power system. However, assessments of 13 selected CCS projects, including one commissioned in 1986, exhibit that such projects considerably underperform. Of them, five CCS projects demonstrated less than a 50% carbon capture rate over their lifetime. While two projects failed after four and seven years of operation, respectively, one project could not even reach the operational phase. Data from two projects were not publicly available. Such a dubious track record requires serious scrutiny before investing in CCS technology.

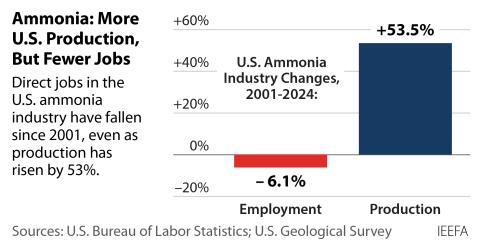

A recent Bloomberg study indicates that ammonia co-firing with coal-fired plants will be considerably more expensive than solar and wind power with battery storage systems. Similarly, blending hydrogen with gas-based plants is unlikely to be cost-effective.

Therefore, unproven and expensive technologies/fuels may lock Bangladesh’s power sector at higher risks, intensifying consumer tariff burdens.

Bangladesh should limit its power capacity expansion spree, laying the foundation for minimising capacity payments and selecting the least-cost route. A gradual promotion of renewable energy through a competitive process will be beneficial. Strong policy measures will also be required to surmount the barriers affecting the country’s renewable energy promotion.

As different estimates and assumptions of the IEPMP are indicative, there is certainly room for adjustments to make the power sector sustainable and resilient in the coming years.

(This article was first published in The Business Standard)