Spin-off or just spin? Adaro's bold plan to achieve net-zero

Key Findings

The world’s sixth-largest coal miner, Adaro Energy Indonesia (Adaro), plans to divest its thermal coal arm, Adaro Andalan Indonesia (AAI), through a public offering to support its decarbonization and net zero emissions targets.

The sale raises questions about whether Adaro’s strategy is a true step toward emissions reduction or simply a balance sheet cleaning exercise that may not lead to actual reductions in Indonesia’s carbon footprint.

There are concerns that prospective new owners of AAI may not uphold Adaro’s commitment to decarbonization and mine rehabilitation obligations.

Adaro Energy Indonesia, the world’s sixth-largest coal mining company, plans to spin off its thermal coal business, Adaro Andalan Indonesia (AAI), through a public offering. Adaro aims to sell approximately seven billion shares in AAI, valued at about US$2.45 billion (Rp37.6 trillion), representing 31.8% of Adaro’s total equity. Shareholders approved the sale at an extraordinary general meeting on 18 October 2024.

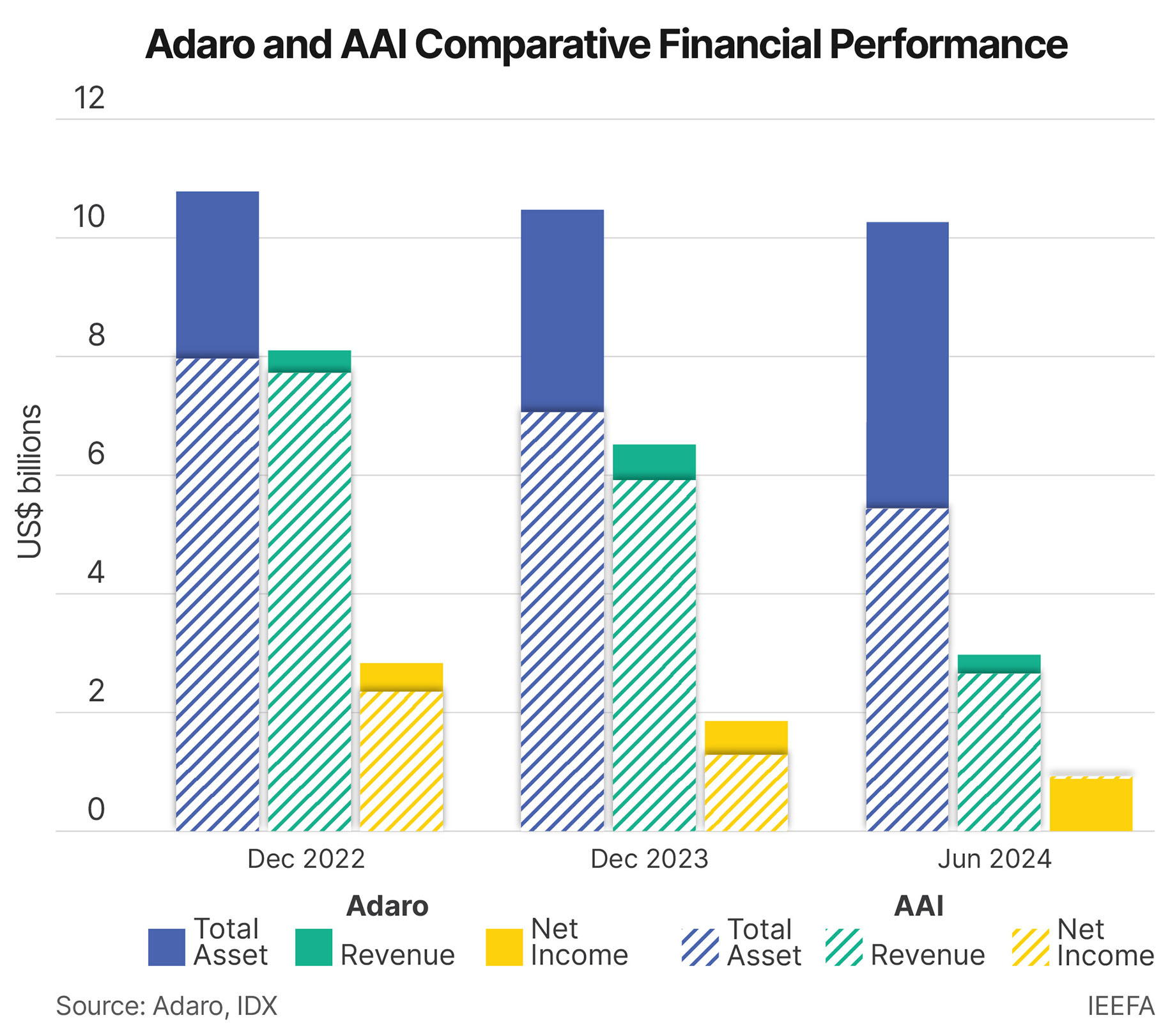

As of June 2024, AAI held 53% of the parent company’s total assets and contributed 89% of total revenue, while its net income contribution exceeds the rest of the group combined. Given AAI’s size, the plan raises questions about Adaro’s intentions. Is it intent on becoming a green energy company or simply passing on the burden of high carbon-emitting assets to new owners? If so, what will happen to those assets?

Figure 1: Adaro and AAI Comparative Financial Performance

What is the motivation behind this corporate action?

Adaro’s subsidiary, AAI, owns several thermal coal mining companies. Thermal coal is considered “the world dirtiest energy”, because burning it is a major source of carbon pollution, which drives climate change. In the seven years since the Paris Agreement in 2015, Adaro is responsible for 0.28% of global carbon pollution and is a major emitter.

In 2023, Adaro published a Net-Zero Emissions (NZE) statement to reiterate its commitment to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, including a roadmap to achieve NZE by 2060 or earlier. The company aims to increase total revenue from non-thermal coal businesses above 50% by 2030. Thus, with the AAI spin-off, Adaro appears to be shifting away from thermal coal to reduce its GHG emissions and focus on its green business. AAI accounted for about 15% of Adaro’s 2023 overall corporate emissions; thus, to achieve its NZE target, further action is required. Removing these assets from the corporate portfolio could be viewed as a step in the right direction.

Adaro has several large green projects in its development pipeline. These include the 1.4 gigawatts (GW) Mentarang Induk hydroelectric power plant project, estimated to cost US$2.6 billion; the 70 megawatts (MW) Tanah Laut wind project (US$153 million); and the 400MW solar project to export electricity to Singapore. Continuing its coal business could jeopardize Adaro’s financing for these plans. Shifting away from coal would give the company access to green financing sources with attractive financing costs and rates.

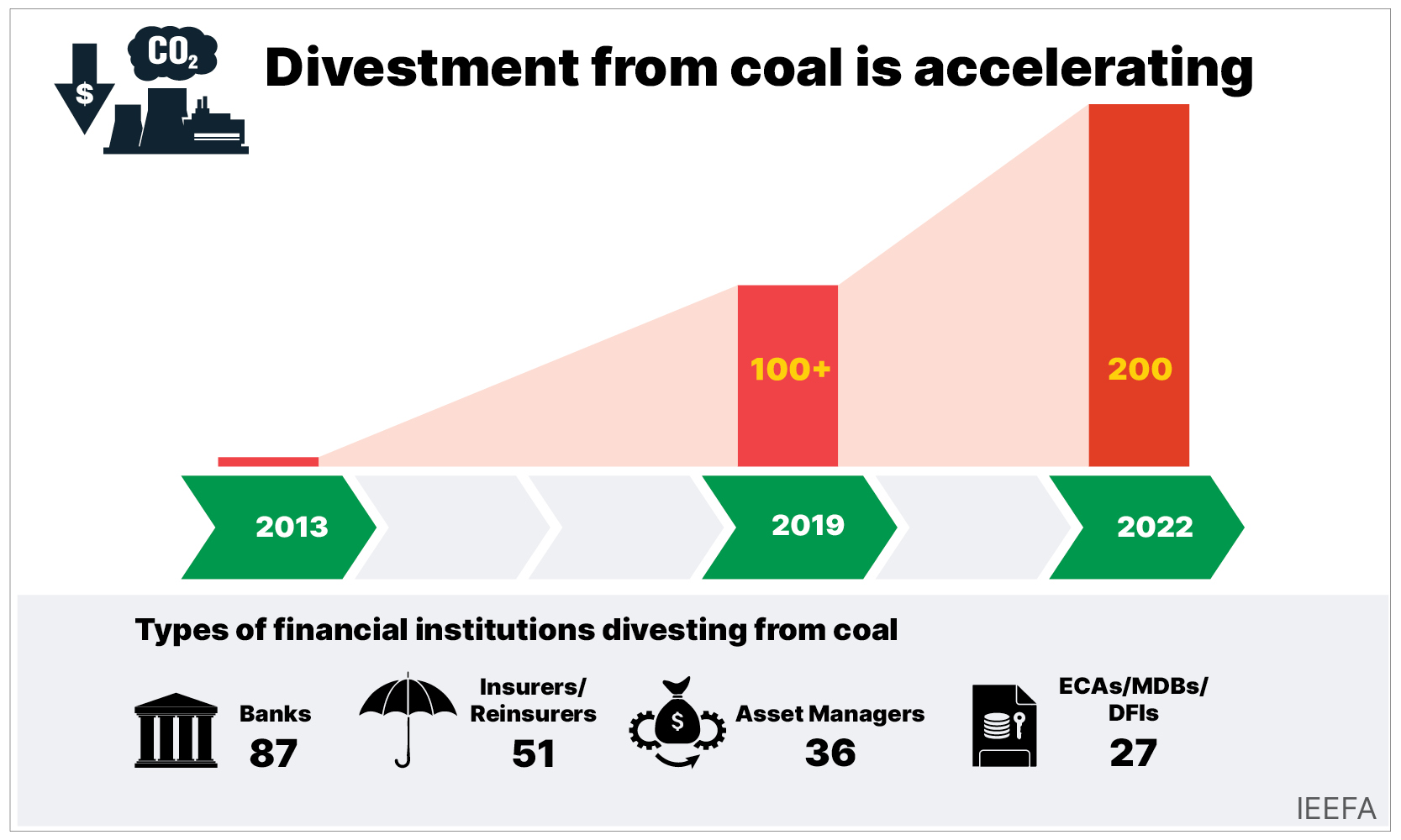

Today, many major financial institutions have environmental, social and governance (ESG) mandates, leading them to divest from thermal coal. Bank financing for the sector fell by 20% from 2016 to 2023. Globally, the number of financial institutions willing to finance or hold coal-related investments is shrinking, with IEEFA identifying 200 institutions exiting coal (Figure 2). If Adaro continues its thermal coal business, its financing options will likely narrow, reducing its competitiveness and potentially increasing financing costs.

Figure 2: Global Financial Institution’s Divestment from Coal, 2013-2022

Source: IEEFA

Foreshadowing this eventuality, in February 2023, Standard Chartered and DBS Bank refused to finance Adaro’s new nickel smelter project as it featured large-scale coal-fired power. Compounding these troubles, in April 2024, car maker Hyundai called off an aluminum supply agreement with Adaro due to pressure from South Korea-based environmental groups.

Although coal can be a lucrative business, it does not necessarily increase shareholder value. Companies that integrate ESG priorities into their growth strategies could outperform on the fundamentals and exceed them in shareholder returns. Furthermore, many major investment houses have developed investment products with sustainable mandates that reflect the fossil fuel sector’s underperformance, its negative long-term outlook and increasing demand for investment products with dramatically less or no fossil fuels.

As more investors prioritize sustainability, the spin-off of AAI could present an opportunity to invest more confidently in a more greener-focused Adaro.

Company’s next actions and ESG commitment warrant scrutiny

Assessing whether spin-offs are net positive depends on what happens to those assets. While sell-downs may serve to “clean up” the parent company’s balance sheet, there still needs to be a pathway to phase out those high-emitting operations. There is growing concern that the spin-off strategy is not the responsible or correct way to achieve carbon emissions targets. A number of institutional investors fear that selling dirty assets could result in the new owners abandoning net-zero targets.

As the spin-off transaction will involve Adaro’s current owners, it remains to be seen if Adaro’s shareholders will take up their options in AAI. If so, will those shareholders maintain their commitment to Adaro achieving its low-carbon goals? Will a retained interest from Adaro shareholders promote the development of a decarbonization plan for AAI or will they take a bifurcated and contradictory approach?

Adaro’s public float of AAI means the buyers’ identity will be known to the public. If the new owners persist with coal-related operations without a transition plan, they may face the same fundraising difficulties and higher costs that prompted Adaro to spin off those assets initially.

Risks facing the AAI deal

If Adaro’s spin-off of AAI does not proceed, it could signal increasing stakeholder pressure for companies to uphold their ESG mandates and ensure that no additional capital flows into coal.

This appears to have been a factor in the failed spin-off of BHP’s New South Wales Energy Coal (NSWEC) unit in Australia. In 2020, BHP looked to sell its NSWEC assets, including the Mt Arthur thermal coal mine, but did not receive a viable offer. The deal carried risks that potential buyers were unwilling to assume. This included restrictions on its thermal coal business, particularly on financing and insurance, which are increasingly expensive and challenging to secure on favorable terms. Additionally, prospective new owners would have been responsible for the rehabilitation of the mine site. In the near term, BHP will need to seek an extension of Mt Arthur’s license from 2026 to 2030, after which the mine will close. Following the failed sale, BHP wrote down Mt Arthur’s value from A$1 billion (US$650 million/Rp10.4 billion) in January 2021 to an A$200 million (US$131million/Rp2.1 billion) liability in August 2021 to account for the mandatory site rehabilitation costs.

Indonesian regulations require mining companies to allocate funds annually into a sinking fund for post-closure mine rehabilitation. Notably, Adaro’s mining assets within AAI also have finite operating lives; for instance, Adaro Indonesia, an AAI subsidiary, has a coal mining permit that expires in 2032, potentially exposing AAI shareholders to the same risks BHP faced at Mt Arthur.

Conversely, if Adaro successfully divests AAI, it may reduce Adaro’s balance sheet emissions, though there is no guarantee that new owners will honor Adaro’s accelerated decarbonization plan and NZE commitment. AAI’s coal mining operations would continue, and, if Adaro succeeds in divesting its entire stake in AAI, it would relinquish control over those operations and any future ESG strategy. A “cut-and-run” strategy for corporate decarbonization may not result in actual emissions reductions and does not align with a sustainable national decarbonization strategy for Indonesia.

Adaro can set an example of how to exit coal responsibly

Adaro’s spin-off of AAI may have started a trend in Indonesia. Following Adaro’s move, TBS Energi Utama (TOBA) also announced it was divesting its stakes in two coal-fired power plants – Minahasa Cahaya Lestari (MCL) and Gorontalo Listrik Perdana (GLP) – with a total capacity of 200MW. This move is projected to reduce TOBA’s carbon emissions by more than 80%, or about 1.3 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) a year. Environmental management plans, if any, for the spun-off assets are unknown.

Depending on how Adaro defines AAI’s assets, it has an opportunity to set a precedent for responsible coal exit strategies. Regardless of whether the sale succeeds, Adaro could choose to monitor AAI’s operations and ensure that new owners fulfill their decarbonization mandate by reducing coal production, not renewing the mining license, and implementing a clear closure plan for mine assets. This would include protecting workers’ entitlements, establishing a sinking fund for mine rehabilitation, and determining post-mining land use. Alternatively, Adaro could walk away entirely.

If investors recognize the ongoing investment requirements for coal, the high costs of mine closures, and the challenges in securing these funds, the AAI deal may appear less attractive. If Adaro falls short of its share placement target, shareholders could be left with both the clean and dirty assets. Decisive, progressive plans are essential to manage these liabilities effectively and allow a greener, leaner Adaro to achieve its sustainable investment goals.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice.