Mountain of coal at U.S. power plants a new threat to coal industry

Key Findings

U.S. power producers have accumulated a 138 million-ton stockpile of unused coal.

The stockpile matches the entire amount of coal that Appalachia is expected to produce in 2025.

Power producers will need to curb future deliveries while they draw down the excess inventory.

The stockpile represents $6.5 billion of unused inventory at a time when coal is rapidly being displaced by renewables.

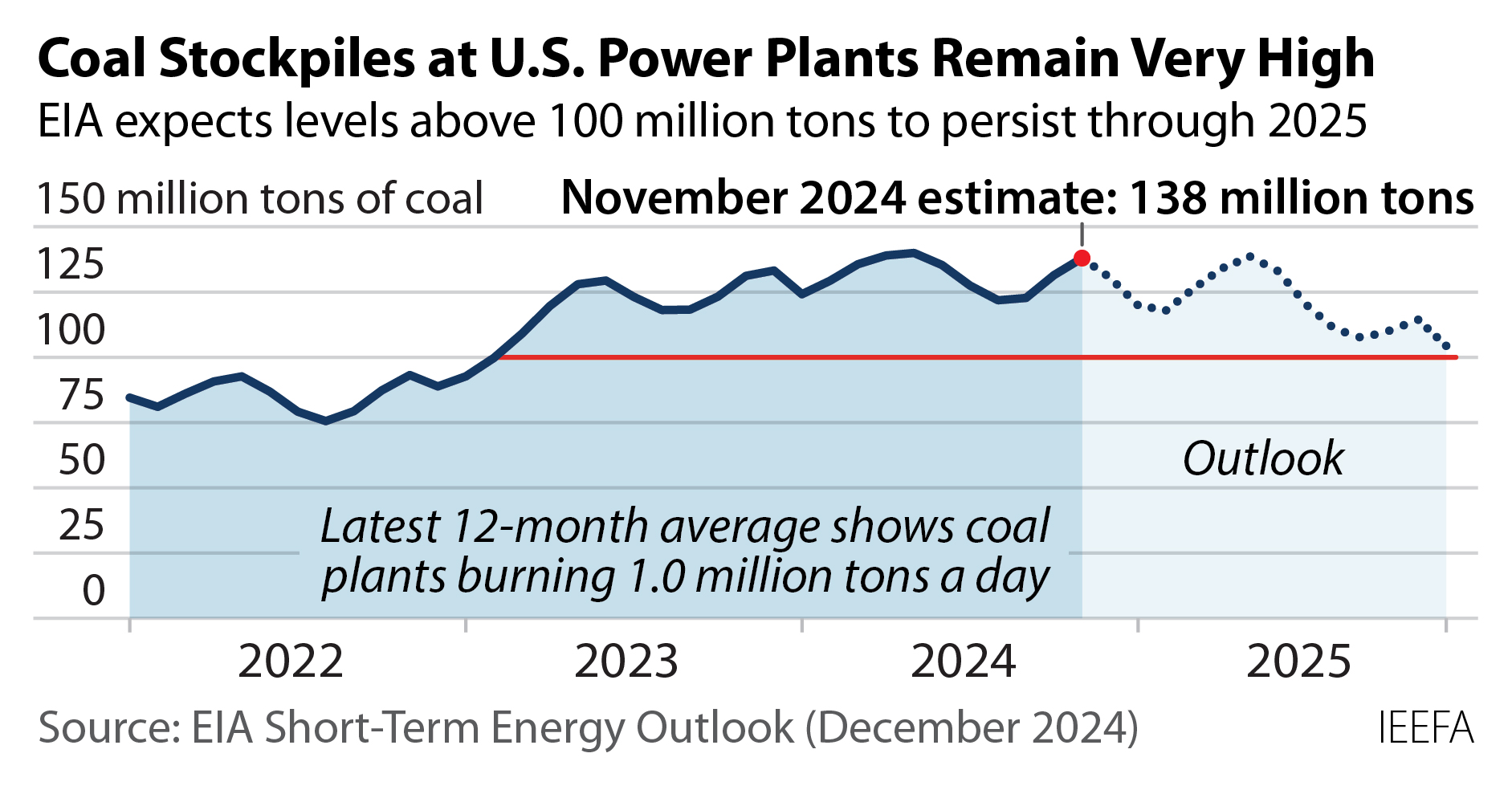

U.S. power producers have amassed a mountain of coal over the past two years that is sitting unused at their coal-fired power plants. The stockpile—about 138 million tons at the end of November, according to the latest Energy Information Administration estimate—is a headache for both utilities and coal producers alike. Worse, the EIA expects stockpiles to remain high, staying well over 100 million tons throughout 2025. For comparison, 138 million tons is the same amount of coal that Appalachia is expected to produce in 2025.

At utilities, the huge stockpiles are not just a storage headache. They’re a financial headache, too—as much as $6.5 billion in unused inventory, based on a $47.22 per ton average cost of coal delivered to power plants (including transportation) from January through September.

No power producer wants that much money idly sitting around. But it has become much harder to burn that coal without losing money. Low gas prices, as well as increased solar and wind generation, have made coal-fired electricity less and less competitive. Periods with high electricity prices during summer heat waves and winter cold snaps also have become fewer and farther apart. As a result, U.S. coal plants now collectively burn just 1 million tons a day, half as much as in 2015, based on the 12-month average through September. At that rate, it would take power producers more than 4 months to use up all the coal sitting around.

In the past when coal stockpiles soared, as happened in 2009, 2012, 2016, and again in 2020, power plant owners worked hard to reduce them to a 50-60 day supply, but it took them anywhere from 16 months to almost three years to do it. This time, it appears, may be different. Rarely has so much coal lingered for so long.

Which brings us to the headache all that coal represents for coal producers. At some point, power companies will need to buy a lot less coal to bring their stockpiles down, even if they keep burning it at the same rate. Since 90% of all thermal coal mined in the U.S. is bought by power companies, coal production would need to fall. In fact, EIA forecasts exactly that. It expects coal output to fall to just 469 million tons in 2025, down from 505 million tons in 2024 and 578 million tons in 2023.

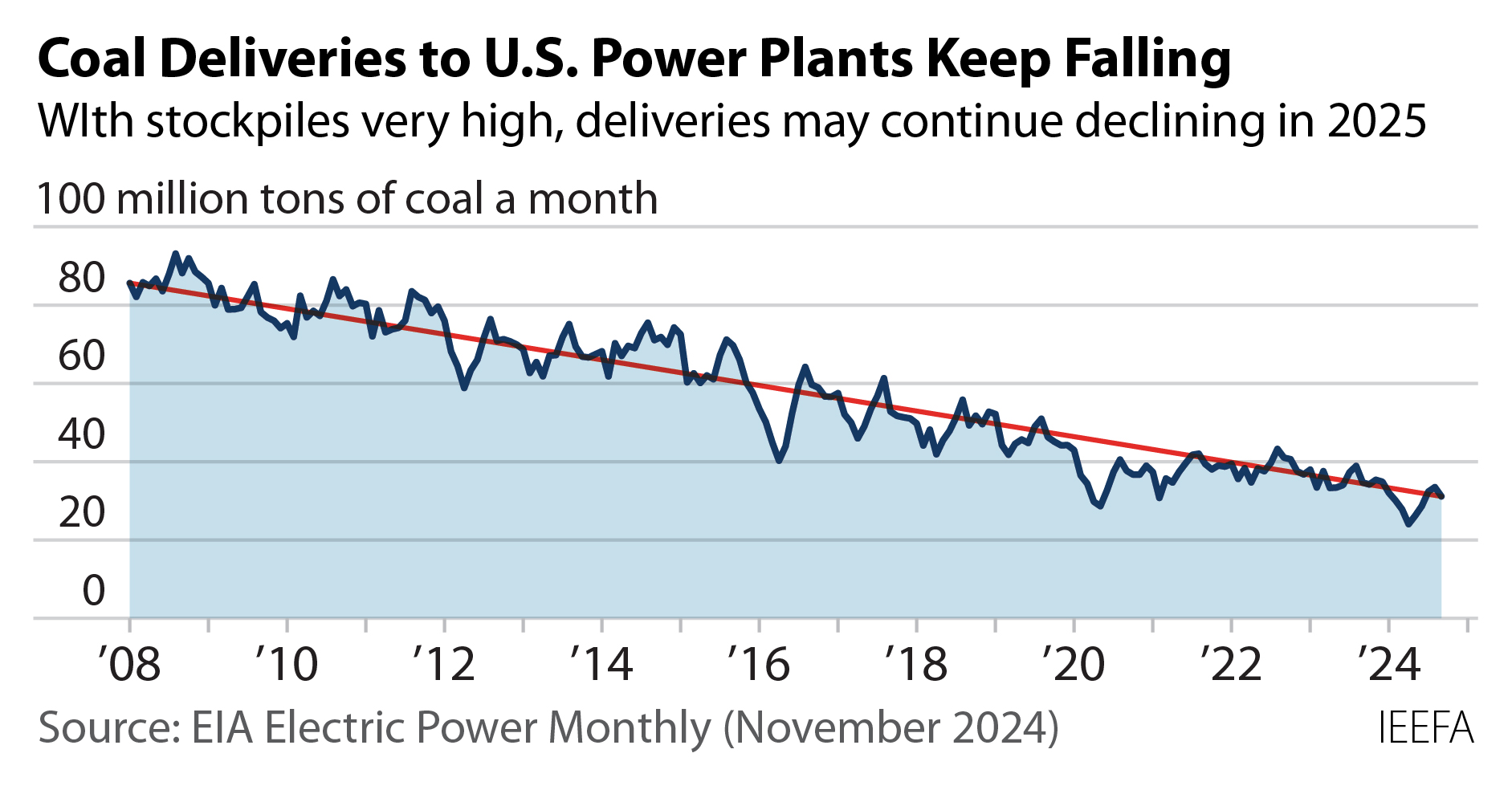

Coal deliveries have already been falling steadily for more than 15 years, from more than 80 million tons a month in 2008 to about 30 million a month in 2024. With huge stockpiles at power plants that utilities need to use, that trend looks set to continue in 2025, and could lead to some months with less than 20 million tons in deliveries.

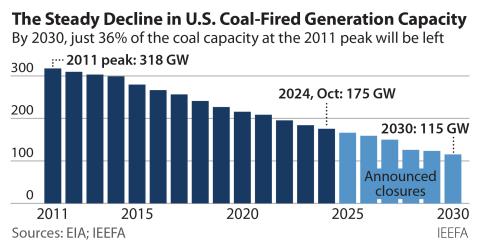

On top of that, the U.S. energy transition continues. In 2025, IEEFA estimates that another 13 gigawatts (GW) of the remaining 173 GW of coal-fired capacity will either retire or be converted to gas, further reducing the market for coal.

And there are still other factors adding to the bleak outlook for coal:

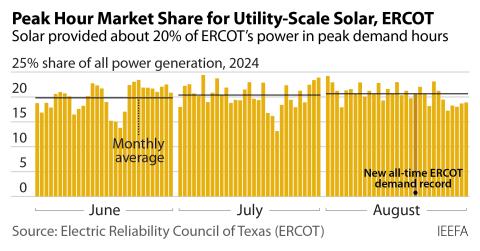

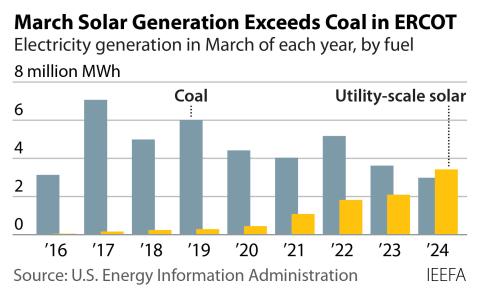

- Rapid growth in utility-scale solar generation, as IEEFA has reported, is one reason why coal’s summer market share has been falling. This year, utility-scale wind and solar will produce more power — 665.8 million megawatt-hours (MWh) — than coal for the first time, which will produce just 641.4 million MWh, according to the EIA’s November Short-Term Energy Outlook. This shift underscores the transition under way in the U.S. power market, where the rapid buildout of wind, solar and battery storage is continually taking market share from coal.

- High power demand during winter cold and summer heat, which historically have been key seasons for coal, are instead getting more and more of that electricity from renewables and gas. As recently as 2021, coal’s daily share of the electric power supply during the winter was at least 20% for almost all of January and February, including five days with more than 30%. During the spring and summer of 2021, coal’s market share was also above 20% from mid-May all the way into October, and was between 25% and 30% for most of July and August. So far in 2024? From Jan. 26 until Nov. 30, coal didn’t have a single day with a market share topping 20%, and it was less than 15% for almost three months in the spring.

- Gas generation, which surpassed coal as the dominant fuel in 2016 and now delivers more than 40% of the country’s power, continues to push coal out of competitive power markets, especially when gas prices are below $3 per million British thermal units (mmBtu), as they have been for most of 2024.

Right now, the biggest threat to coal production appears to be far too much coal sitting at coal plants. As power producers try to bring those stockpiles down, they’ll also need to cut their coal deliveries significantly. Yet the longer that mountain of coal persists, the deeper the delivery cuts and ultimately production cuts will have to be, as more coal plants fade away and more power comes online from newer, less-expensive energy sources.