Indonesia’s nickel edge yet to show up in its electric vehicles

Key Findings

Indonesia rolled out an electric vehicle (EV) incentive program this month for 250,000 two-wheelers (2Ws) and 35,900 four-wheelers (4Ws) in 2023. Various rationales from reducing imported fuel consumption to lowering emissions were outlined by the government, not least the leveraging of Indonesia’s prized nickel resources.

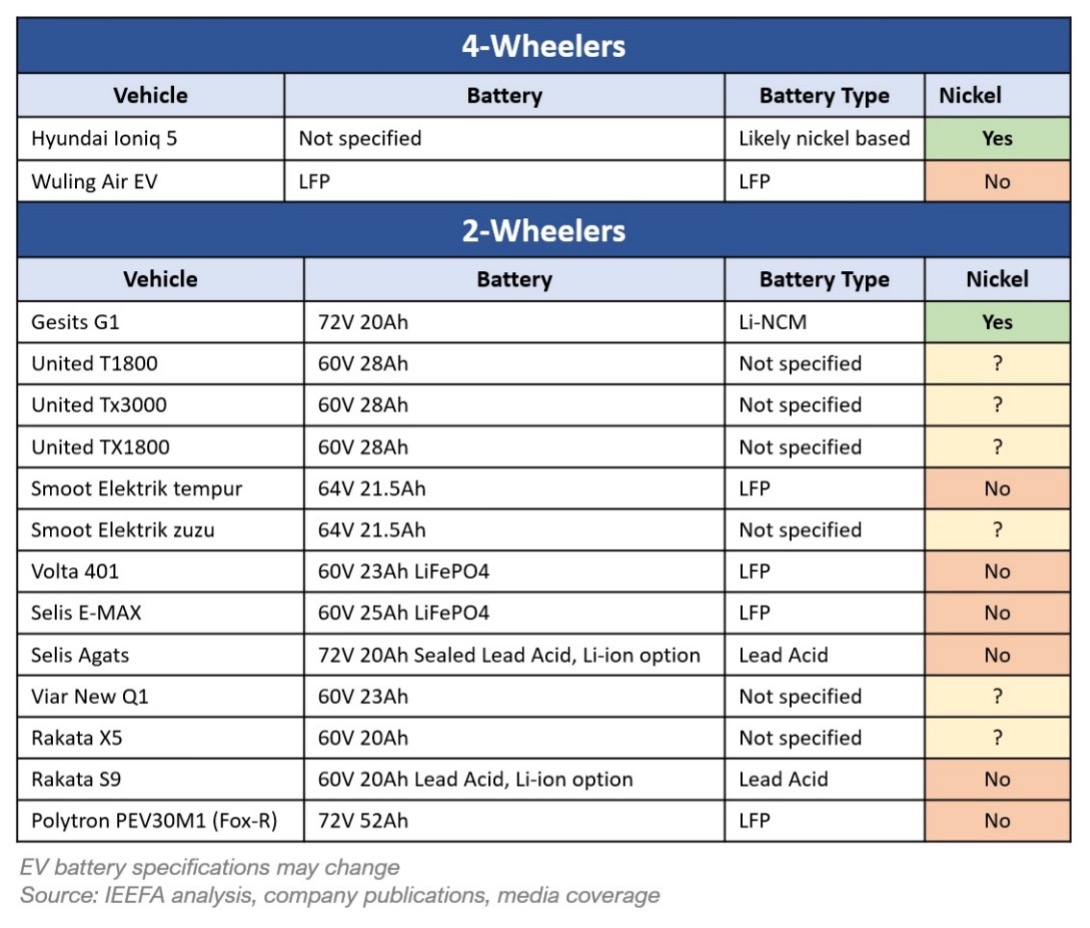

Three-quarters of EV cars sold in Indonesia last year do not use the nickel battery, opting for a cheaper iron-based version. A similar trend could potentially be observed in electric two-wheelers (2Ws). Whether Indonesia’s EV push will actually use its nickel remains to be seen.

With Indonesia claiming a strong leverage emboldened by nickel, it has the power to address environmental and social concerns associated with its nickel ventures.

Current EV push appears to ride on nickel-less battery instead

Indonesia rolled out an electric vehicle (EV) incentive program this month for 250,000 two-wheelers (2Ws) and 35,900 four-wheelers (4Ws) in 2023. Various rationales from reducing imported fuel consumption to lowering emissions were outlined by the government, not least the leveraging of Indonesia’s prized nickel resources.

Why the urgency for EV incentives now? The most likely answer is to attract two major 4W EV automakers to invest in Indonesia: BYD and Tesla. The 2W incentive is probably driven by separate factors, including attempts to accommodate distributive justice concerns and reduce fuel subsidy. The program is expected to send shock waves through current auto players by displaying the government’s commitment to diverge from the business-as-usual trajectory.

What is happening in the region? Southeast Asian (SEA) countries are vying for EV automakers’ investments in response to the global rise of electric vehicles. Indonesia is in close competition with Thailand, the regional leader in auto production. South Korea’s Hyundai and Wuling of China have established a presence in Indonesia, while leading Chinese EV maker BYD this month began construction of its first SEA factory in Thailand. The Philippines and Vietnam have also shown interest; as a nickel producer, the former is second only to Indonesia worldwide, albeit slightly disadvantaged by its higher cost of electricity. With each country introducing its own EV incentives, the competition in SEA is tightening.

How will Indonesia benefit from EV adoption? The country can reduce growing oil imports, cut life-cycle emissions from transport and deepen the nickel-battery-EV industry establishment. Fuel subsidy could decrease, depending on which types of vehicles will be displaced. Subsidy cuts are more likely for the 2W segment as 4W incentives are insufficient to persuade lower-end 4W consumers to switch to electrics. In recent years, domestic electric 2W setups have grown in numbers, though many still rely on imported high-value batteries.

Indonesia has so far attracted only two major 4W EV automakers, Hyundai and Wuling. Interestingly, the Wuling Air EV, which comprised three-quarters of EVs sold last year, uses an iron-based battery called lithium iron phospate (LFP), a lower-cost alternative with no nickel content. A similar trend will likely be observed in the 2W segment, where the cheaper LFP has the advantage in cost-sensitive markets. In Q1 2022, half of all new Tesla cars around the world used LFP, significantly in China.

Three-quarters of EV cars sold in Indonesia last year do not use the nickel battery, opting for a cheaper iron-based version. A similar trend could potentially be observed in electric 2Ws. Whether Indonesia’s EV push will actually use its nickel remains to be seen.

How do low-to-no-nickel batteries relate to Indonesia’s “nickel downstreaming” efforts? Globally, the use of nickel-based batteries will continue to grow, potentially in more demanding applications such as longer-range vehicles. Ironically, though, Indonesia’s wealth of nickel has yet to translate into clear directions as to whether the nickel battery will dominate EV growth in the country. As most of the population own 2Ws and low-to-medium-end 4Ws, cost considerations may tilt the market toward the more affordable LFP option. Current initiatives seem to focus on building a nickel-related industry and deepening the battery industry buildout while piggybacking on efforts to domestically produce lower-cost EVs, with or without nickel batteries. Meanwhile, plans are underway to set up LFP battery factories. Ultimately, whether Indonesian nickel will be competitively priced to give auto players an advantage in the domestic EV market remains to be seen.

Fig.1 Nickel on the Periphery in Indonesia’s Incentivized EV Lineup

Will the incentives be enough to promote domestic EV adoption? The incentive program is a commendable move to overcome initial adoption barriers, but widespread adoption remains unlikely in the absence of other policy reinforcements to support charging infrastructure and conventional vehicle restraints. A multi-year commitment is expected for a continual expansion of EVs. India’s renowned EV subsidy program was designed on three-year batches. It is acknowledged that deploying longer-term policy is likely difficult considering the approaching election less than a year away, yet this also raises the urgency for the government and stakeholders to demand a closer watch on the effectiveness of the EV incentives.

In pushing for EVs, Indonesia is on the right track as the alternative path is to continue importing oil into oblivion. But creating an optimal and committed regulatory setting will be needed to build a credible market.

What is on the watchlist? The government should anticipate incentivizing a spike in sales which is not followed by sustainable market development. Clear milestones and the trend of price reduction over time should be monitored closely.

- Lessons from other markets will need to be incorporated in observing and fine-tuning the program, including in anticipating incentive misappropriation risks.

- Technological preferences can combine with incentives to promote EV features which address long-term consumer concerns, such as the driving range, safety, and battery-swapping capability.

- Infrastructure must be built in parallel to the incentives.

The incentive program is likely a race against competing SEA countries for EV manufacturing. Despite the nickel-driven narrative, the battle is probably about getting battery and EV factories up and running. Belated formation of an EV supply chain could risk Indonesia being left behind, taking on the environmental burden of nickel exploits while accruing little benefits of EV adoption.

The United States’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), established last year, incentivizes U.S.-based clean technologies, including EVs, while limiting incentives for products associated with “foreign entities of concerns”, which could include Chinese-related entities. The European Union’s recently proposed Net Zero Industry and Critical Raw Materials acts also aim to incentivize an EV-related supply chain buildout in the bloc. These initiatives could have material impacts on Indonesia which need to be anticipated.

With Indonesia claiming a strong leverage emboldened by nickel, it surely has the power to address environmental and social concerns associated with its nickel ventures. And if it doesn’t, then where is the leverage?

As battery chemistry evolves, concerns about the environmental footprint of the nickel-associated industry will intensify and need to be addressed to maintain Indonesia’s long-term competitiveness. External initiatives such as the IRA and the EU’s legislative acts could help open the door to more diverse and balanced nickel-based investments in Indonesia, raising the bar for industry standards in the process.

The call for a responsible nickel supply chain will come from all sides: EV end-users, manufacturers and the Indonesian public. With Indonesia claiming a strong leverage emboldened by nickel, it surely has the power to address environmental and social concerns associated with its nickel ventures. And if it doesn’t, then where is the leverage?

This commentary is also available in Bahasa.