Closure of last New England coal plant marks significant energy transition milestone

Key Findings

New England’s last operating coal plant is scheduled to be retired by 2028, but will likely close much earlier.

The Merrimack plant, owned by a private equity firm, has only survived because of capacity payments.

The Merrimack plant's owner plans to add solar at the site, and build battery storage at its other New Hampshire coal plant, which hasn’t run since 2020.

The announcement on March 27 that New England’s last operating coal plant, Merrimack, will retire by 2028 is a significant milestone in the region’s energy transition.

Granite Shore Power, the owner of the 439-megawatt (MW), 1960s-era plant in New Hampshire, reached an agreement to cease coal use with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Sierra Club, and The Conservation Law Foundation. As part of the agreement, Granite Shore Power also agreed to officially retire the 139MW, 1950s-era Schiller coal plant, also in New Hampshire, by 2025 (although the plant has been closed since 2020).

Granite Shore Power has been wholly owned by private equity firm Atlas Holdings since 2022. In addition to the two coal plants, Granite Shore owns three other New Hampshire facilities—the 400MW dual-fueled (oil and gas) Newington plant and two small combustion turbine units in the northern half of the state.

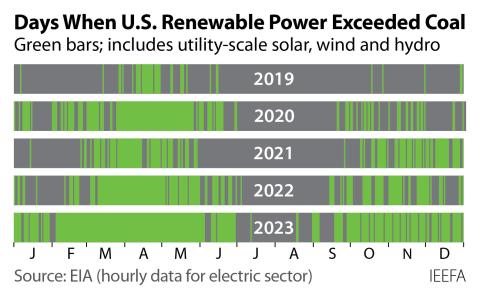

The retirement announcement confirms what has already been known for some time: Coal-fired power has become uneconomic in the region, as well as almost everywhere in the U.S. Increasing amounts of lower-cost solar, wind, and battery storage continue to make gains in providing the electricity needed by consumers and industry.

Merrimack, for example, has barely run in recent years, operating at just 4% of its potential in 2023, and less than 10% in seven of the last eight years. The plant has only survived economically through payments from New England’s capacity market, a type of power insurance program that only requires a plant to run so that it can be called on when demand for electricity is high. The payments, which allowed Merrimack to collect millions of dollars a year, were critical because the high-cost power from the plant was rarely competitive in the energy market.

It is likely that Merrimack will stop running well before 2028. Starting in June 2026, the plant will no longer get the capacity-market payments that have sustained it: Granite Shore’s bids were unsuccessful in the last two capacity-market auctions, which are competitive, and covered June 2026 through May 2028.

Even now, the plant’s ongoing operations are uncertain. Merrimack has been out of compliance with its air quality permits—it was polluting much more than allowed—for more than a year, and it was ordered by the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (NHDES) to complete a successful air quality test by March 23, just days before the retirement announcement. Although Granite Shore was required to provide preliminary test results to NHDES within five days, it does not have to submit final results until May. It is not entirely clear what actions NHDES might take if the plant fails the test, but the economic math for Granite Shore Power is clear. If the cost of pollution-control repairs and maintenance rises too much, the company is unlikely to make the investment and will shut the plant down.

Granite Shore said it is already focusing on investing in the future of New England’s grid. In another reflection of the region’s energy transition, the company said it will develop a battery-storage facility at Schiller, near the Atlantic coast. The station owner plans to use those batteries to store power—including offshore wind power when it becomes available—at times of low demand, selling it back to the grid during higher-demand times. This shifting use for old coal plants has been occurring in many places in the United States recently, as companies seek to continue using the valuable grid infrastructure and transmission access at the sites, especially as government funding for these changes has become available.

At Merrimack, Granite Shore says it is also planning to move toward renewables, redeveloping as much as 400 acres toward solar generation and other uses for a “clean energy center.”

In making these moves, Atlas Holdings, the private equity money behind Granite Shore Power, appears to be finally acknowledging both the progress and reality of the energy transition in the Northeast, while shifting its investments to make money in the new energy landscape.

The benefits to the New Hampshire communities where the plants are located could be significant. The Schiller plant, for example, has been idled since early 2020, with all of the workers laid off and the waterfront location sitting unused. With a firm retirement date and a plan to repurpose the plant, it should clear a path toward a much-needed cleanup of the site, provide new jobs as the battery storage is built and the grid infrastructure renewed, and contribute more revenue to the City of Portsmouth than a deteriorating, unused plant. The same advantages could be even more important to Bow, N.H., a largely rural area between Concord and Manchester where the Merrimack plant is located.

If Atlas Holdings sticks to its agreement to both retire the coal plants and redevelop the sites into productive energy assets fully participating in New England’s energy transition, it could provide an important example to other private equity firms: How to successfully revitalize legacy fossil-fuel energy investments by embracing the shift to more sustainable power.