Catalysing renewable energy finance in Bangladesh

Download Full Report

View Press Release

Key Findings

Bangladesh will require up to US$980 million annually until 2030 to meet the goal set out in the Renewable Energy Policy 2025. Post-2030, the country will need up to US$1.46 billion annually until 2040.

Policy uncertainty, offtaker and currency risk, land acquisition challenges, and a downgraded sovereign rating may limit capital flows into the renewable energy sector in Bangladesh.

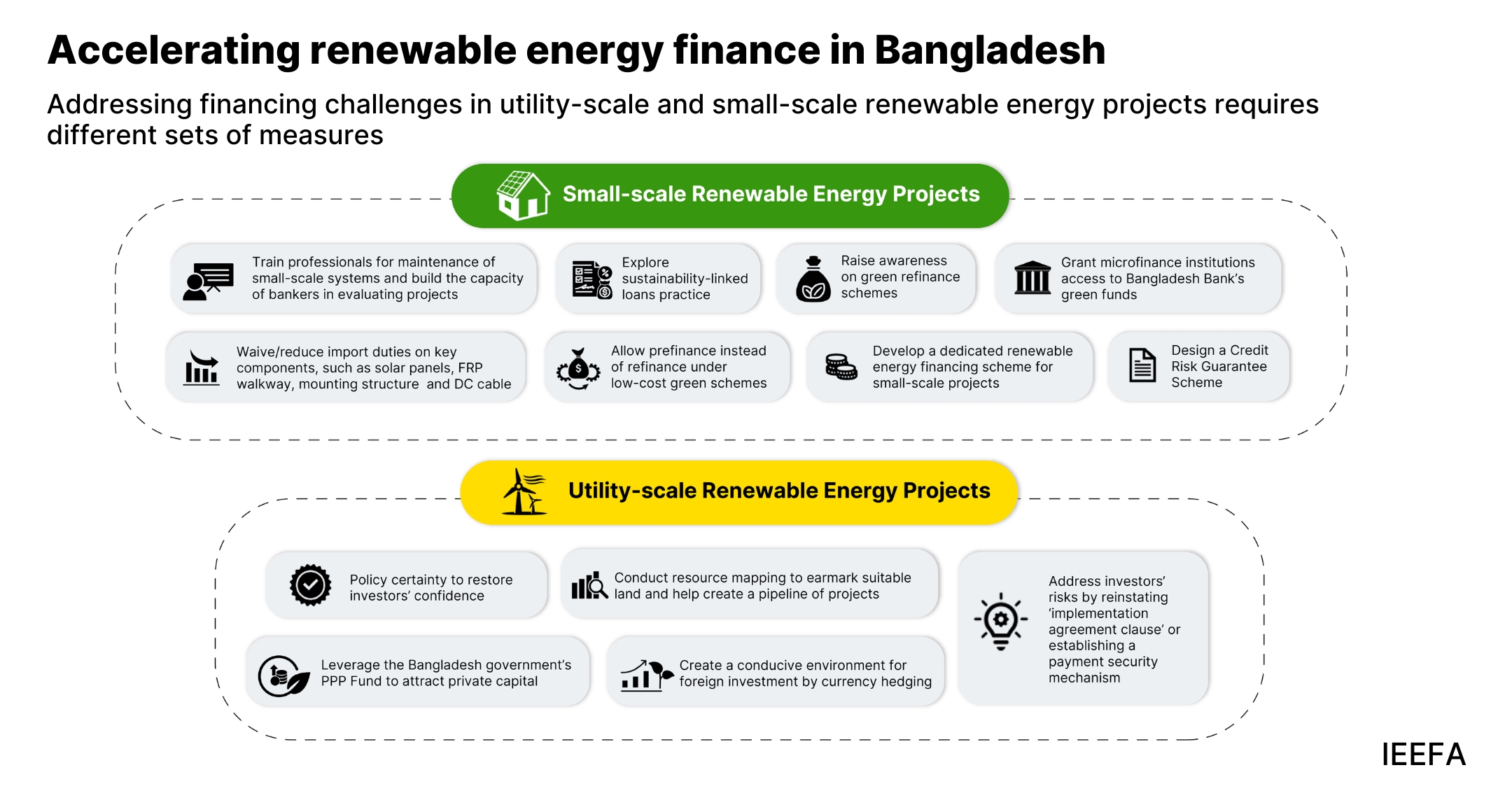

A credit risk guarantee scheme, a dedicated green finance facility with scope for pre-finance, and an import duty waiver on solar accessories can help accelerate the flow of finance for small-scale renewable energy projects.

The country needs to create an enabling environment for investment in utility-scale projects through streamlined policy and regulations.

Bangladesh stands at a pivotal moment in its renewable energy transition, with potential to significantly reduce its dependency on costly fossil fuels. As its power sector subsidies are likely to surge by 55% year-on-year in the fiscal year (FY) 2024-25, increasing the country’s renewable energy capacity is crucial.

The government has approved a new Renewable Energy Policy, which significantly raises the country’s clean electricity ambitions. The new target is to generate 20% and 30% of electricity from renewable energy sources by 2030 and 2040, respectively. Our ballpark estimates suggest the country requires between US$933 million and US$980 million annually until 2030 to meet the new target. Post-2030, the country will need between US$1.37 billion and US$1.46 billion annually until 2040. Public finance is unlikely to entirely meet these funding requirements, necessitating large-scale private investment.

However, there are several challenges to attracting private investment in Bangladesh’s renewable energy sector. Policy and regulatory changes, off-taker risk, technology and performance risk, weak project pipelines, a cumbersome loan disbursement process, land acquisition challenges, currency volatility, and lower sovereign rating limit capital flows into the sector.

Abrupt policy changes have dented investor confidence, minimising the inflow of foreign capital. Local investors and sponsors are not keen to invest in utility-scale renewable energy projects due to the lengthy land acquisition process. The removal of the “implementation agreement” clause, similar to a sovereign guarantee, deters them from submitting proposals against the government’s tenders. On the debt front, Bangladesh’s low credit ratings will increase the cost of foreign loans, which are essential for the country’s economic growth and energy transition. The devaluation of the Bangladeshi Taka by a massive 27% against the US dollar between May 2022 and January 2025 further complicates project financing. Loans are even more difficult to secure for small projects. Financial institutions often demand high collateral and perceive small-scale projects as risky, limiting access to financing for such initiatives. High import duties on renewable energy system components add to the cost of small-scale projects.

The government can earmark land for utility-scale projects through proper resource mapping. It can also address land acquisition challenges through the Public-Private Partnership model. This can help mobilise private investment in renewable energy through special economic zones, thereby circumventing land acquisition uncertainties. Policy certainly and a gradual transition from unsolicited project award to a competitive bidding process will help attract the consistent investment the sector needs until 2040 (see Figure 1).

The government can help establish a currency hedging facility to mitigate currency risk. Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), international climate finance institutions and bilateral development financial institutions can support the creation of this facility. The Bangladesh government may reinstate the “project implementation clause” as a sovereign guarantee, dispel any uncertainty over payment owing to the Bangladesh Power Development Board’s hefty subsidy burden or establish a funding mechanism to provide revenue assurance to renewable energy producers, mitigating counterparty risks.

To accelerate renewable energy investments, the government can actively engage with MDBs to secure concessional funding, which can lower the cost of capital for projects and, therefore, attract private investment.

A low-cost dedicated renewable energy financing scheme can support small-scale projects, such as rooftop solar and solar irrigation. Since traditional financial institutions are reluctant to finance small-scale projects in rural areas, Bangladesh Bank can consider allowing Micro Finance Institutions to access low-cost green funds.

Pre-finance instead of refinance can incentivise building owners to avail Bangladesh Bank’s green refinance schemes. As Bangladesh Bank has changed the terms and conditions of green refinance schemes several times in recent years, raising awareness will help end users utilise these low-cost loan facilities.

While the government has reduced import duty on inverters, it should consider doing the same for other key components of small-scale solar projects.

The Sustainable and Renewable Energy Development Authority can implement a capacity-building programme to develop the technical capacity of service providers and ensure the effectiveness of small-scale projects. It can further develop the capacity of bankers to finance small-scale distributed renewable energy projects.

The transition to renewable energy in Bangladesh is not merely imperative for decarbonisation; it is an economic necessity. Policy and regulatory reform, institutional development, and low-cost financing can position Bangladesh as a low-carbon economy and a climate leader in the Global South. The government, international organisations, financial institutions, private investors, and renewable energy companies should collaborate to create a conducive environment that fosters innovation, investment and sustainable growth.