BP’s retreat is a reality check for investors

Key Findings

For several years, some major investors and analysts have looked to BP as an example of an energy company taking the global energy transition seriously.

BP is now reportedly abandoning key planks of its 2050 net-zero pledge, and it’s part of a much broader sector trend.

BP and its peers are failing to demonstrate a cohesive plan for managing shareholder value amidst a changing economy.

The retreat should serve as a wake-up call for those who expect the fossil fuel energy sector to serve as a good-faith partner in the energy transition.

According to a recent report, BP is abandoning its pledge to reduce oil and gas production en route to net zero. The news gives further insight into how fossil fuel companies are navigating the energy transition — and raises yet more questions about their ability to manage shareholder value amidst a decarbonizing world.

The announcement rolls back a key plank of BP’s ambition to achieve net-zero by 2050 or sooner, which as announced in 2020, centered around a “decade of delivery” that would “reshape its business” through diversification into low-carbon energy and a 40% decline in oil and gas production by 2030. At least on paper, the goal vaulted BP ahead of many of its peers, and contributed to arguments claiming that some oil and gas producers were embracing the energy transition.

At the time, industry analysts at Wood Mackenzie lauded the detailed guidance that “leaves stakeholders with a much clearer idea of where BP is headed over the next decade, how it will get there and what that means for the value proposition.” Wood Mackenzie wrote that “no company of BP’s stature … had gone as far, or committed so unequivocally, to transforming itself in the face of the energy transition.”

To major institutional investors such as CalPERS, BP’s adoption of a net-zero goal was vindication of a seat-at-the-table approach: explicit evidence of a company responding to investor concerns and working collaboratively to mitigate structural risks.

Others were a little more circumspect. When BP’s plan was first announced, some commentators warned that it excluded important parts of the company’s carbon portfolio, and failed to properly account for emissions across the full oil and gas value chain. Moody’s Investor Service, for example, observed in a briefing that “[i]ntegrated oil and gas companies are not well-positioned for a transition to a lower-carbon future [since their] core business … is particularly exposed to carbon transition risk under a declining demand scenario over the long term.”

The Moody’s opinion ranked BP as a leader in a laggard industry, ahead of many peers but still pursuing pathways that resulted in material exposure to risks from the transition away from carbon; Further evidence of concrete actions in the medium term, it declared, would be necessary for evaluating transition readiness moving forward. IEEFA at the time struck a similar chord, warning BP and peers that recent strong rhetoric would need to be followed up by continued, accelerated action to meet investor expectations.

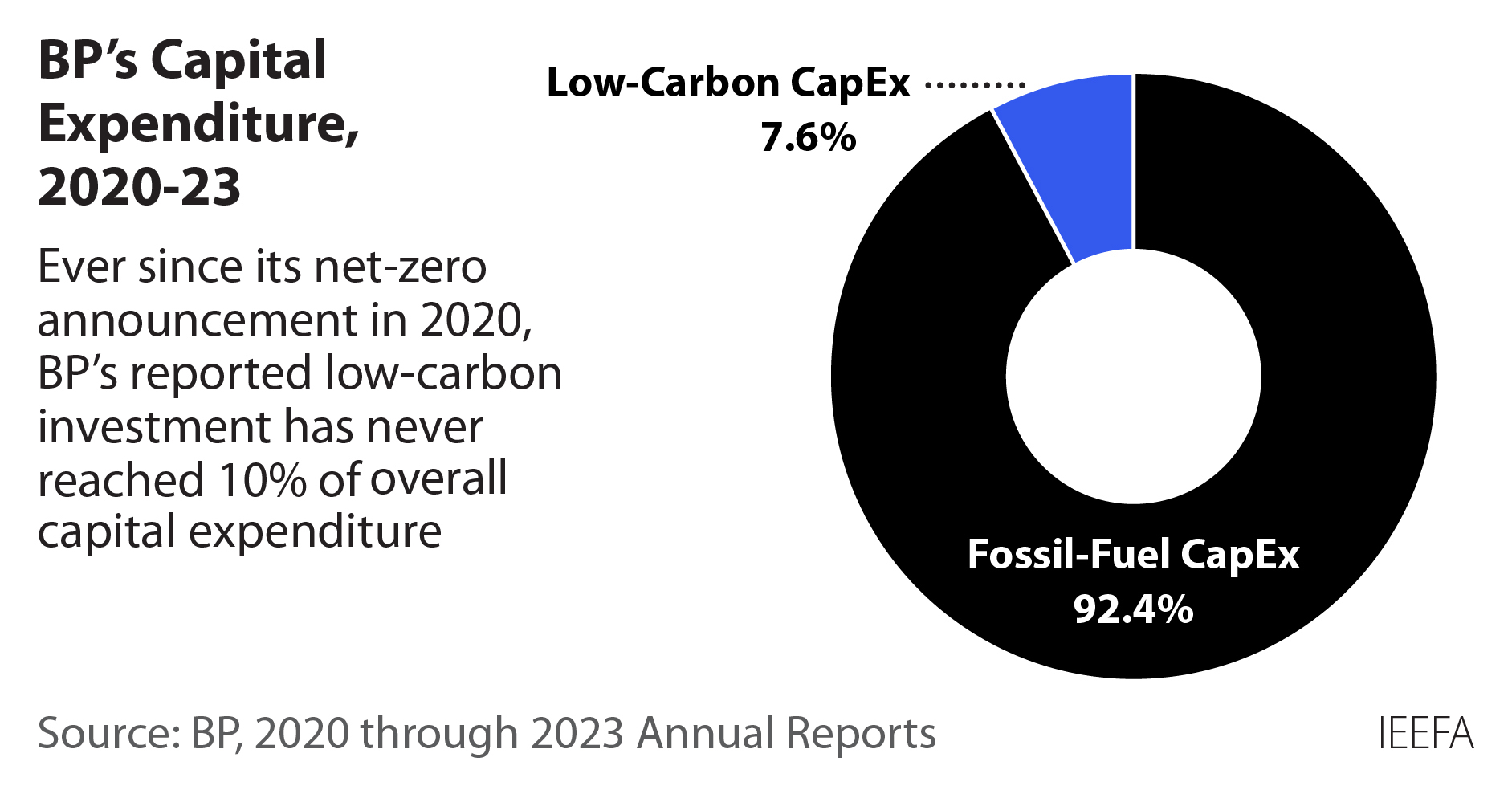

So far, history has largely vindicated the caution. In 2023, BP announced that it would aim for only a 25% production decrease by 2030, down from the original 40%. Earlier this year, as the company exited some high-profile renewable energy, it advanced long-term oil extraction efforts in the Gulf of Mexico, Iraq and Azerbaijan. Between 2020 and 2023, as the “decade of delivery” was taking shape, the company’s percentage of low-carbon capital expenditure never broke into the double digits.

Indeed, the company’s present backtracking is hardly without precedent. In 2001, facing depressed oil prices and reputational threats, BP rebranded as “Beyond Petroleum.” Yet as prices rose over the coming decade, this framing was abandoned as the company renewed its focus on oil and gas. Investors had hopes that this time would be different, but once again, the company has over-promised and under-delivered.

With BP now dropping its already-weakened 2030 goals, the company widens a longstanding chasm between rhetoric and action. Markets will now be looking to the company’s upcoming shareholder meeting in early 2025 for clarification about the company’s plans. For now, the midcentury net-zero aspiration remains technically on the books, but without the sort of interim steps needed to meaningfully establish credibility. As BP navigates a tumultuous moment—years of past stock market underperformance, a leadership transition and unsettled energy markets in the present, and long-term foundational challenges to its core business model— its recent reversals are unlikely to dispel lingering shareholder questions about its future.

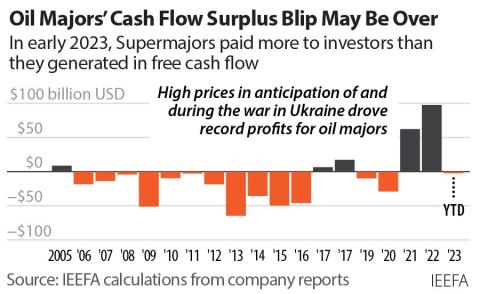

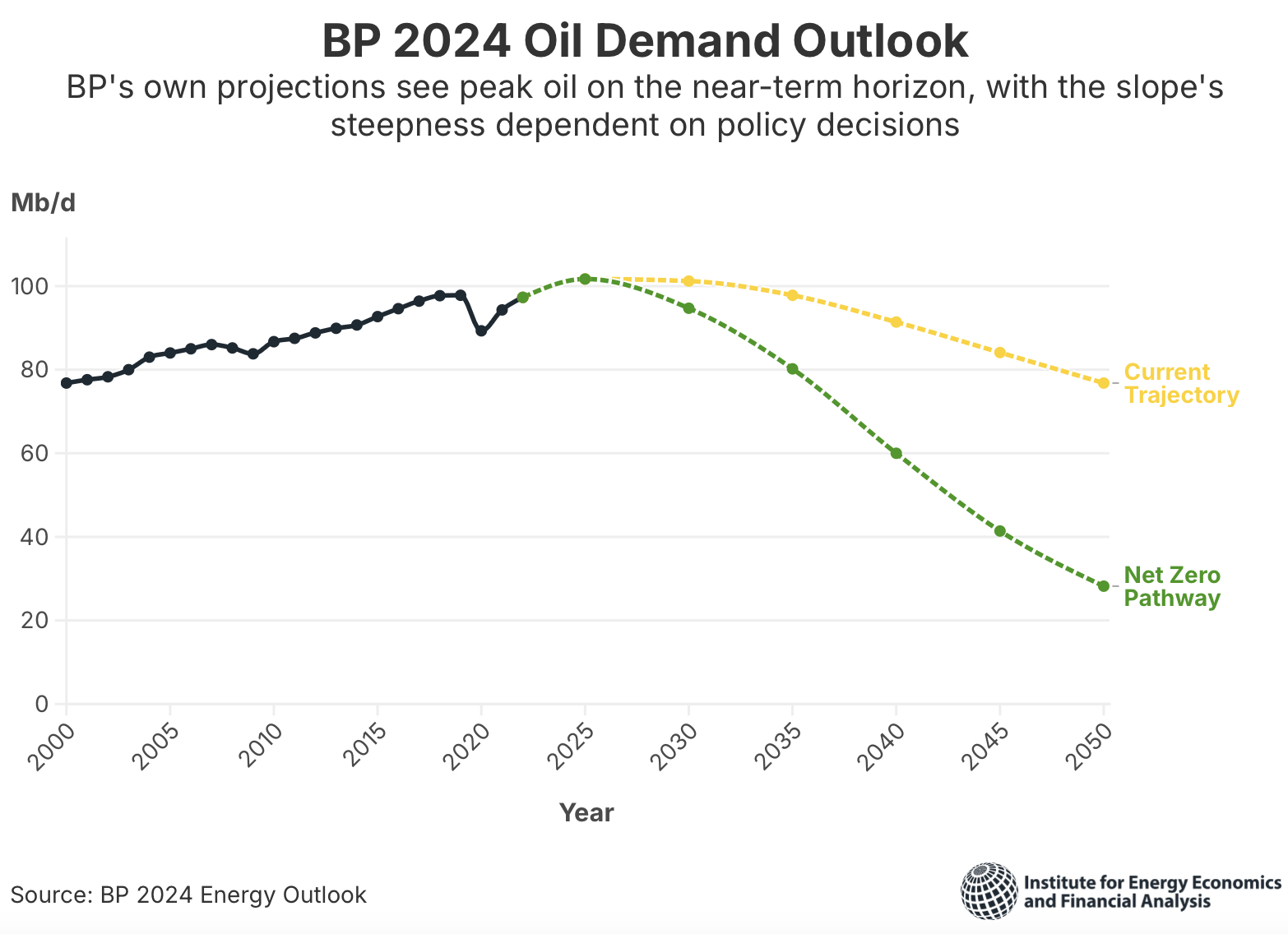

BP has attempted to justify its retreat by pointing to Russia’s invasion and heightened attention to global energy. But while energy markets have indeed been volatile in recent years, spurring near-term supply crunches that gave oil and gas companies a substantial but fleeting revenue spike, has this meaningfully changed the long-term picture? BP’s published outlooks offer some insight, with peak oil projected within the decade and significant demand destruction set to occur by 2050 across multiple scenarios. In fact, BP projects less 2050 oil demand now than it did when it initially made its net-zero pledge.

If taken at face value, the original net-zero strategy represented an effort to get ahead of the energy transition and build up alternative revenue streams while hastening the economy’s broader shift. In its current strategy, BP seems content to chase short-term profits at the expense of substantive long-term planning.

To be sure, this is far from BP’s story alone. While the major fossil fuel companies still purport to recognize climate change as a material factor in markets, peers across the market are softening their energy transition ambitions. This has not gone unnoticed by credit ratings houses and other analysts that are developing new capabilities to evaluate not just what companies say about climate risks, but how they are performing against them. When measured up against these standards, raters are increasingly warning of the constellation of long-term risks facing fossil fuel producers. The uncomfortable reality for investors is that despite years of targeted persuasion efforts, leading fossil fuel producers are moving backward in key ways. A decarbonizing economy threatens the fossil fuel industry’s core business model, and the sector does not seem to be offering a cohesive and consistent plan for navigating this changing world.

To be sure, there are different ideas about how the fossil fuel sector should pursue net-zero alignment. One school of thought says that the oil majors should diversify into cleaner energy. But it has never been evident that inertia-bound incumbents are well-positioned to abandon their existing long-term investments and drive transformation at scale, especially as compared to newer, more nimble market entrants.

Another school of thought says that oil majors should diversify into other parts of the carbon value chain, such as petrochemicals. But is that just swapping one growth-limited industry for another facing secular decline? A third approach would have companies embrace a managed phasing out of production and return cash to shareholders as demand falls. But can an industry whose historic business model has relied so heavily on growth and expansion exercise such discipline and foresight?

In practice, BP and peers seem to be choosing none of the above, actively expanding oil and gas in hopes that the world blows past its climate commitments. For the investors who have previously taken these companies at their word and bet on their seriousness about the transition, recent retreats are a wake-up call. Corporate executives may be hoping that these decisions will help them satisfy short-term targets. But long-term investors and other systemically-minded financial actors should ask whether the visions underpinning such companies’ strategies truly align with their own — and whether such companies can be good-faith partners in achieving their goals.