Grid governance, utility obligation reform, and local engagement can reignite Japan’s renewable energy growth

Innovative regional approaches in Fukushima and Akita demonstrate scalable models to overcome transmission, regulatory, and utility challenges

Despite its recent lackluster renewable growth, Japan can meet its pledge to triple renewable power capacity by 2030 by resolving structural and institutional bottlenecks, according to a new report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

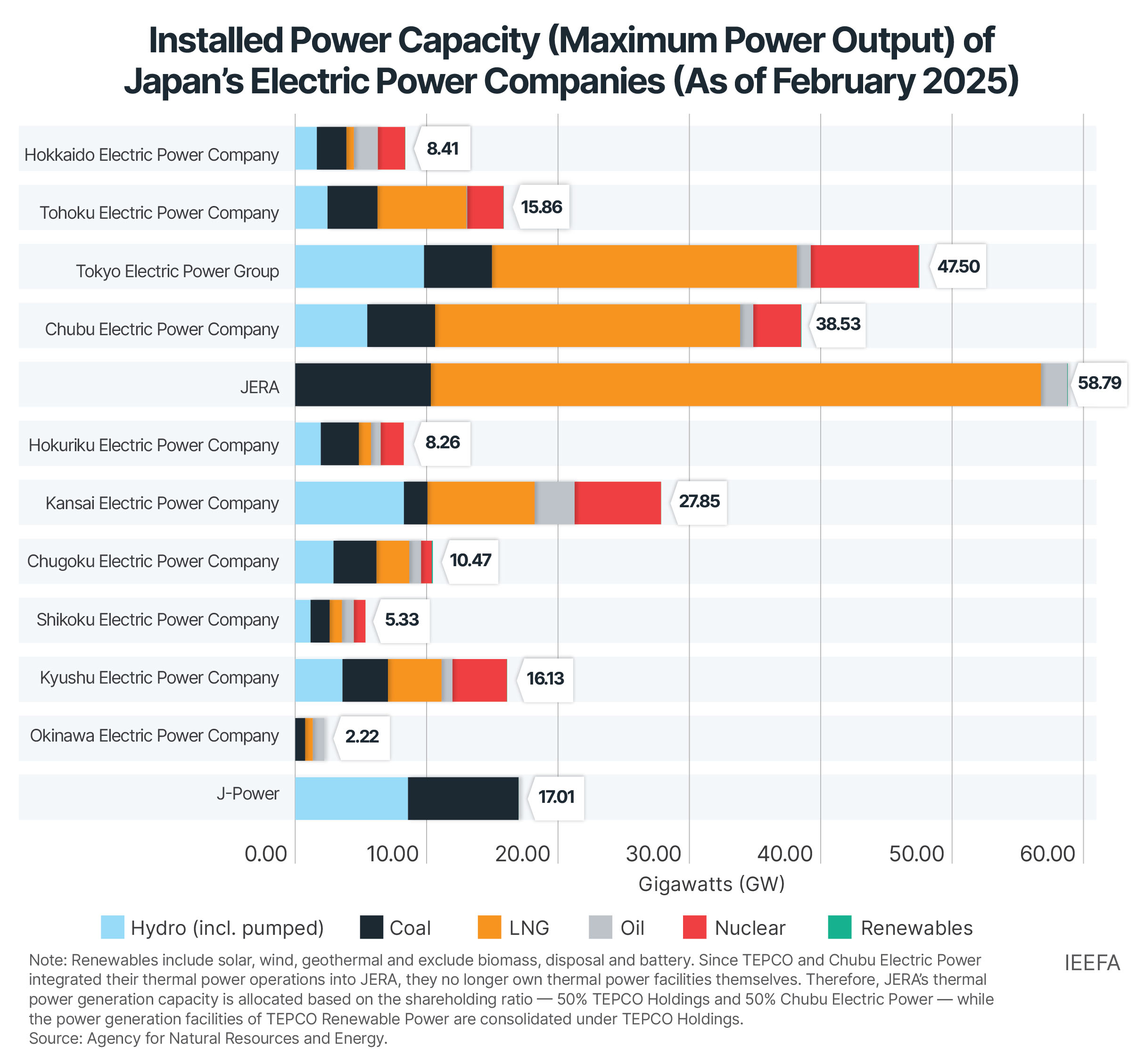

Ten major Japanese electric utilities control nearly 75% of installed power capacity but own less than 0.3% renewable capacity (excluding hydro), prioritizing fossil fuel and nuclear assets.

A record 52 renewable energy project developers exited the Japanese market in 2024, including eight bankruptcies with liabilities over JPY10 million, double the number recorded in the previous year.

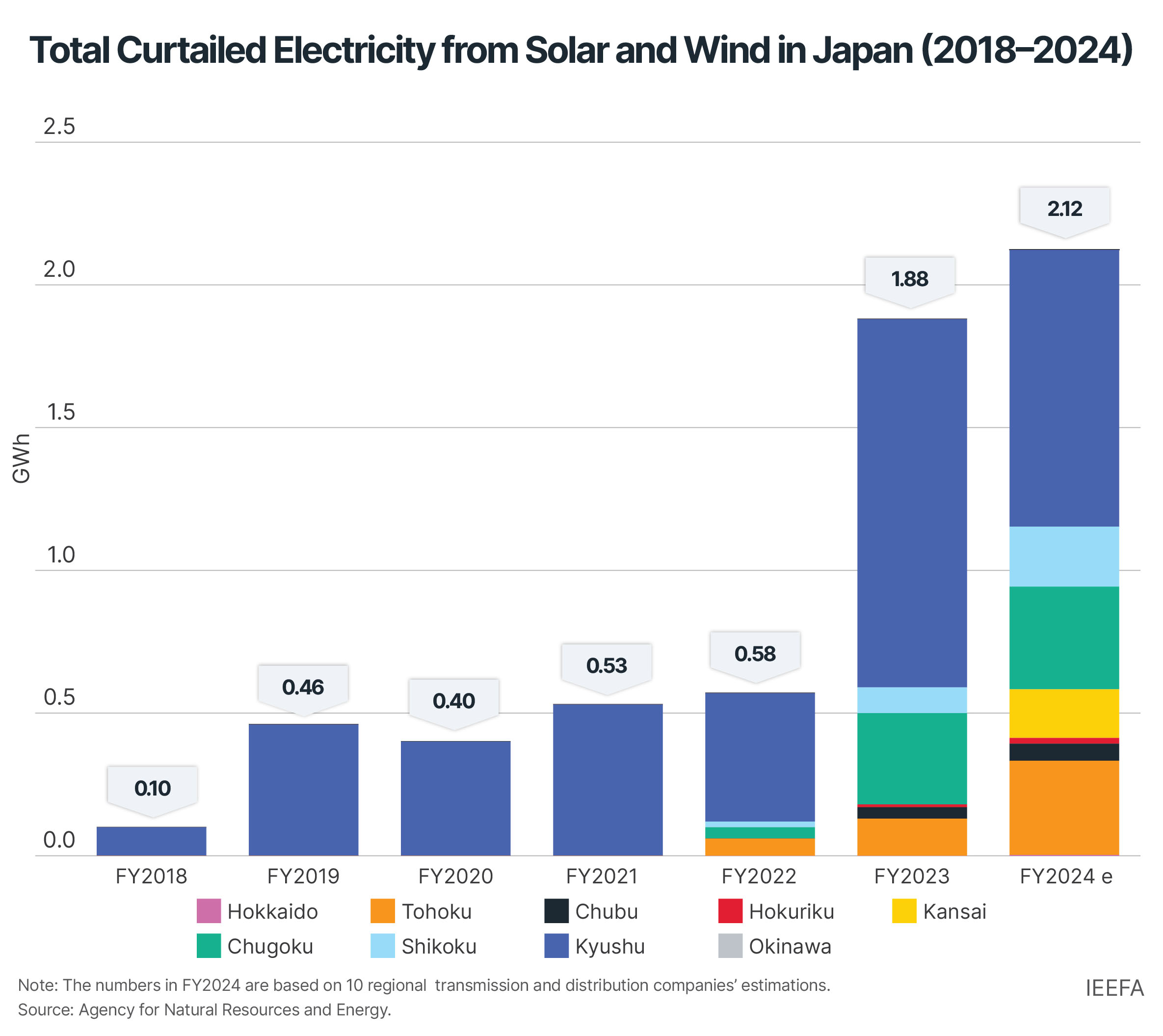

According to report author Michiyo Miyamoto, IEEFA’s Energy Finance Specialist, Japan, the country’s renewable energy growth challenges are not technological or economic but systemic and regulatory, such as grid congestion, market inflexibility, output curtailment, and major utility inaction.

“Contributing factors include political and corporate reluctance to transition to renewables and limited use of relevant policies. Technical and infrastructure constraints causing curtailment, and geographic discrepancies between renewable development costs and benefits create additional obstacles,” says Miyamoto.

Several regions in Japan have demonstrated that meaningful progress is possible. Prefectures such as Fukushima, Saga, Akita, and Hokkaido have set local renewable energy targets, engaged communities, and mobilized regional finance to support clean energy expansion.

“Japan should focus on scaling these successful regional approaches instead of relying on fossil fuels for backup," notes Miyamoto. “Priorities should include reforming grid access rules, modernizing market design, strengthening enforcement of the existing Non-Fossil Certificate (NFC) obligations for major utilities, and enabling deployment paths such as power purchase agreements (PPAs).”

Revisiting target and market design

Utilities have underutilized the NFC system, which allows them to meet procurement targets without owning generation assets.

“Most NFCs purchased are derived from non-renewables, such as nuclear. Weak enforcement of the legally-binding 44% non-fossil fuel obligation further reinforces this trend,” says Miyamoto.

Unlike the Feed-in Tariff (FIT), which was introduced in 2012 and guaranteed a predetermined purchase price for renewable energy, the Feed-in Premium (FIP) was launched in 2022 to provide a variable premium in addition to wholesale electricity market prices.

The FIP system poses particular challenges for small and medium-sized enterprises. While the goal was to encourage producers to participate in wholesale markets and develop more flexible business models, including storage and aggregation, these entities lack the financial resilience to withstand the revenue volatility of a tariff tied to wholesale market prices.

“Under the FIT scheme, prices decreased, and eligible technologies were limited. The FIP system resulted in unpredictable prices, jeopardizing stable project development. Additionally, curtailment risk has increased significantly because of insufficient grid capacity. Therefore, revenue projections for new projects have become less certain,” explains Miyamoto.

Overcoming the urban-rural divide

According to the report, Japan lacks a comprehensive framework for transmission development, and there are significant physical and economic gaps between renewable energy supply and demand in urban and rural regions.

Renewable generation is concentrated in rural and coastal areas, while demand centers are in metropolitan regions. Urban areas face land scarcity and higher project development costs, while rural regions host most large-scale renewable installations. However, long-distance transmission remains underdeveloped due to complex permitting processes and transmission operators’ limited finances.

In resource-rich regions such as Kyushu, renewable developers face delays and high grid access costs. Limited transmission capacity and dispatch rules that prioritize thermal power plants (exempting them from curtailment below 30%-50% of output) further restrict renewable generation.

Yet in prefectures like Fukushima, Akita, Saga, and Hokkaido, proactive local leadership, early zoning, transmission investment, and engagement with local finance have enabled tangible renewable energy growth. These regions are models for what can be accomplished through localized strategies.

“In Akita Prefecture, offshore wind development progressed efficiently through early negotiations with local fisheries cooperatives. Local governments played a key role in securing community support, which paved the way for nationally designated promotion zones. This model — early local engagement with national-level streamlining — has also been adopted in Aomori and Hokkaido Prefectures, where offshore wind projects have progressed similarly,” says Miyamoto.

Unleashing Japan’s renewables potential

The report outlines recommendations to accelerate renewable energy deployment in Japan. These include establishing a specific target to triple renewable energy capacity through auctions and procurement mandates, and promoting the expansion of corporate and community PPAs through regulatory and financial support.

“There are over 220 RE100 members in Japan who cannot fulfill their renewable mandates due to the lack of clean energy connections and supply,” says Miyamoto. “Public credit guarantees or risk-sharing mechanisms for smaller buyers, reduced legal costs, and stronger policy incentives for public institutions to purchase renewable electricity can help facilitate entry in the underdeveloped corporate PPA market.”

Meanwhile, expanding renewable energy auctions can support price discovery, developer participation, and project financing.

“Japan’s recent auctions have proven the viability of offshore wind projects and established a replicable framework for rapid scaling. The country can attract domestic and global capital into a previously dormant sector, utilizing clear regulation, robust competition, and designated infrastructure,” states Miyamoto.

This momentum, combined with legal reforms enabling development in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), is opening vast new deployment areas. In addition, the participation of international developers is fostering a competitive market characterized by advanced technology and strong project execution expertise.

“If grid connection and supply chain constraints are addressed, Japan could become Asia’s leading offshore wind hub,” says Miyamoto.