Uncomfortable Questions in the Wake of Peabody’s Sale of Its Remaining Stake in a Costly Midwestern Coal-Fired Plant

Peabody Energy’s decision to sell its share of the Prairie State Energy Campus for 23 percent of its original value is just the most recent—but perhaps the starkest—reminder that this project is a financial failure.

IEEFA has chronicled financial weaknesses of the Illinois plant since before it opened in 2012, and warnings around its viability go back to 2008.

Peabody yesterday said it had agreed to sell its stake in the plant for $57 million, which is 23 percent of Peabody’s original equity infusion of $246 million. That original $246 million stake represented 5.06 percent of the $5 billion in bonds on the project let by state power authorities in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri and Kentucky. Peabody’s sale arguably reflects a market valuation on the plant itself of $1.1 billion—far less than what is owed on it.

We note that before Peabody walked away from the plant this week, Prairie State officials spent much of the last six months extolling its improved technical performance. As we’ve said before, however, the plant could run at 100 percent of capacity and still lose money. The Peabody transaction comes after the company carried the Prairie State plant at a loss on its books in 2012 and 2013. Presumably even with the recent uptick in performance, the plant lost money for the company in 2015 too.

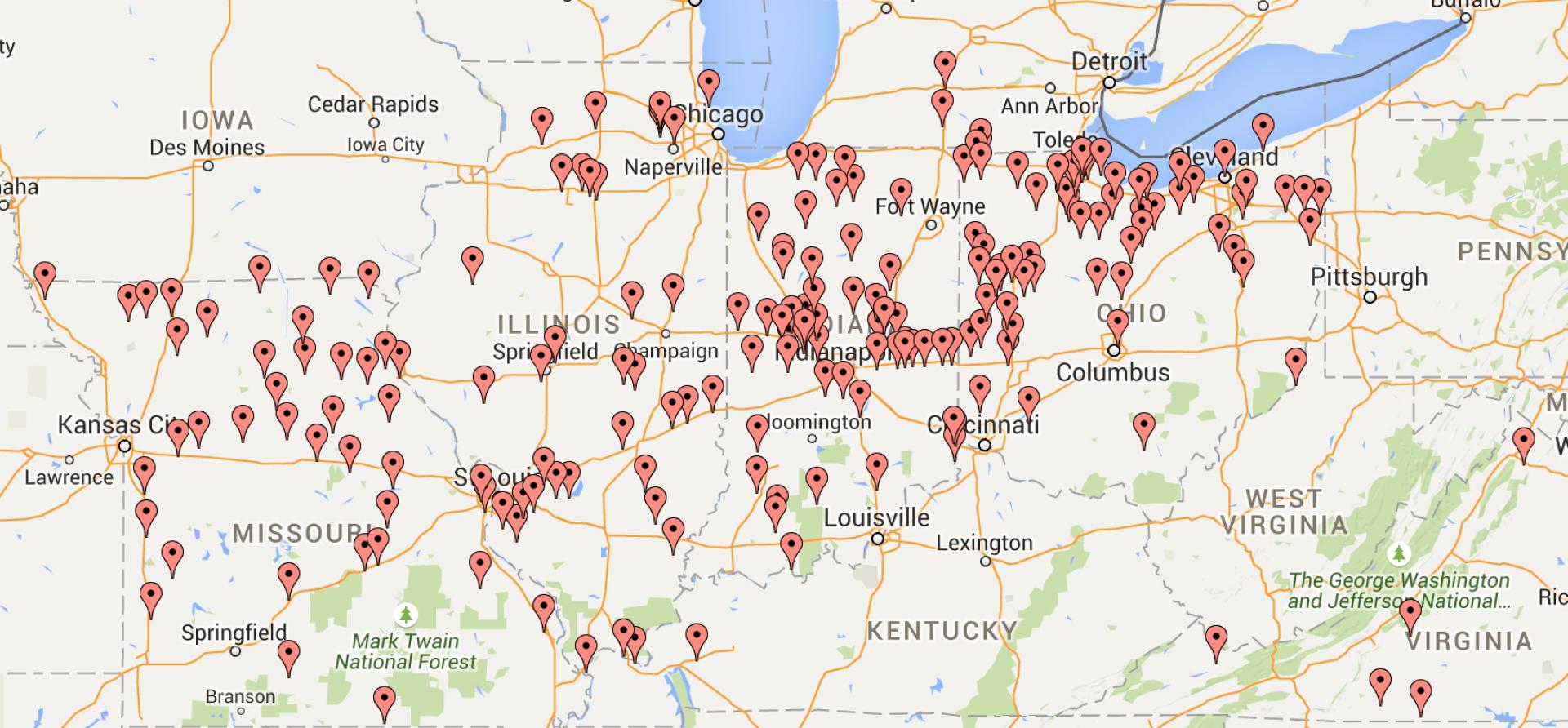

Prairie State is also causing financial stress for most of the communities that have signed 30- and 40- year contracts to buy its electricity. IEEFA has documented these circumstances in several communities in the Prairie State portfolio.

American Municipal Power in Ohio, for example, owns a 23 percent share in Prairie State. It carried the plant value for its 23 percent stake at $1.285 billion at the end of fiscal year 2014, showing $1.6 billion in various forms of bond indebtedness and other notes outstanding against the plant.

PEABODY’S SALE RAISES CRUCIAL QUESTIONS FOR THE REMAINING OWNERS. GIVEN THE MARKET MEASURE ESTABLISHED BY THE PEABODY TRANSACTION, can AMP continue to value the plant at $1.285 billion on its books? Will the other state power agencies in Missouri, Illinois, Indiana and Kentucky that co-own Prairie State have to drop the asset valuations they carry on the plants in their financial filings? Would their liabilities and assets then be out of balance? Would these entities remain solvent? What should bondholders think if there is no underlying asset that props up the value of the bonds? Where is there recourse in the event of a default by a local government?

There will undoubtedly be debate on this point. We understand that the market position of Peabody, a for-profit company is different from that of the public-sector power agencies and municipalities that are still in the deal. We understand, too, that they may treat asset valuations differently for technical accounting purposes.

But let’s be clear: This plant is not worth $5 billion today and may never have been worth that much. And let’s be clear on this point: The communities left footing the bill are paying too much for electricity and are now paying for a power plant that bears no relationship to the value of the bonds used to pay for it.

When the original deal was struck, Peabody agreed to stay in for five years unless the board at Prairie State allowed them out earlier. Why is it that Peabody can cut and run and the participating communities remain bound and gagged?

Unless these communities can find a real champion either in their state governments or by banding together in some fashion, they will be stuck for the full contract period, paying for electricity that is more expensive than the market offer and for a plant that is really worth on 20 percent of its supposed value.

(A related side note of interest: We’ve seen U.S. coal plants in this country sell for far less than the 20 percent of original value being offered in this transaction. The buyer in this sale, the Wabash Valley Power Association in Indiana, is also a Peabody customer, buying coal from its Bear Run mining operation in Indiana for the Wabash Valley Power.)

Lest we cry for Peabody’s financial losses, remember that the company sold the power plant a mine—Lively Grove—with coal that was otherwise unmarketable. The company also made profits from the development, construction and management of the Lively Grove mine, which was built to supply Prairie State. It also sold the power plant a piece of property that serves as part of the plant’s ash-fill capacity. We don’t know what Peabody’s continuing role might be in the management of Lively Grove, or if it even has one, but we expect their losses there will be quite minimal.

How is it that the governors of each of these states remain dumb, the attorneys general deaf and the state auditors and comptrollers blind to this obvious fiscal calamity? Only the small towns of Hermann, Mo., and Batavia, Ill., are raising legal questions so far, although others may be joining their ranks soon.

Tom Sanzillo is IEEFA’s director of finance.