Sustainable aviation fuel: Not a panacea, but likely helpful if key issues are resolved

Download Briefing Note

Key Findings

In the effort to reduce the aviation industry’s carbon footprint, sustainable aviation fuel isn’t a panacea but increasingly shows potential as a promising alternative to fossil fuel.

According to the EIA, global commercial jet fuel demand is expected to grow in the coming years and SAF can help the industry meet its sustainability goals, especially in the near term.

While SAF holds great promise, widespread adoption faces several challenges including cost and environmental concerns.

Technological advancements, coupled with growing environmental awareness, are encouraging the adoption of SAF across the aviation industry.

Introduction

The aviation industry faces challenges in the effort to reduce its carbon footprint. Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) isn’t a panacea but increasingly shows potential as a promising alternative to fossil fuel. However, cost barriers and other concerns must be overcome to reap potential benefits from the fuel.

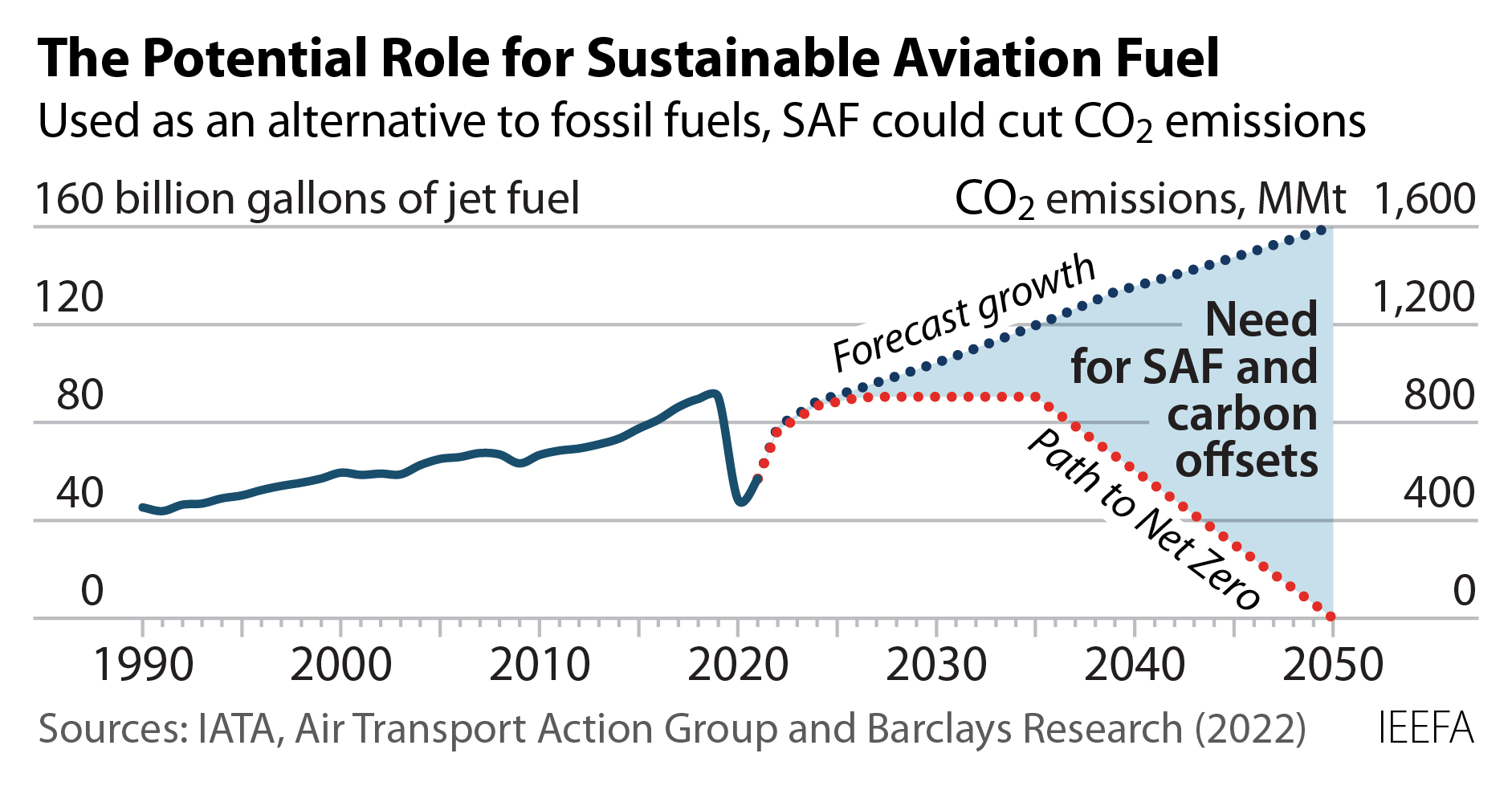

Aviation is a substantial emission source and is getting worse as fuel economy measures fail to curb rising demand

Aviation emissions in 2022 reached almost 800 million tonnes per year (mmtpa) of carbon dioxide (CO2), representing about 2% of global energy-related CO2 emissions. This marks a significant—although partial—rebound from the pandemic-driven downturn, with emissions returning to approximately 80% of pre-pandemic levels. According to the International Air Transport Association (IATA), an airline industry trade advocacy organization, the expected 2021-50 carbon emissions on a “business as usual” trajectory is more than 21 gigatons of CO2, which is an approximately 13% compound annual growth rate (CAGR). The IATA reports that the airline industry has set a goal to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by 2050.

The easiest way to lower aviation-related emissions would be to improve fuel economy. But based on International Energy Agency (IEA) data, the average fuel efficiency in aviation has improved by less than 2% over the last 10-year period, while expected growth in the sector is more than 4% CAGR for the next 10 years. Based on the IEA data, it is evident that the easier work has been done in terms of efficiency improvement, and the current engine technology could be approaching the boundaries of material science. The rate of improved efficiency is likely to slow in future generations.

Figure 1: Projections for Jet Fuel Demand and Emissions