Risk of AI-driven, overbuilt infrastructure is real

Key Findings

Advocates of increased fossil fuel infrastructure designed to meet the needs of data centers may be overstating the case for new plants.

Two of the nation’s largest independent power producers are warning investors about the potential for overbuilding.

The utility industry is planning for about 50% more data center demand than the tech industry is projecting.

While advocates argue that increased fossil fuel infrastructure is needed to provide power for artificial intelligence, the reality is that the AI boom is slowing.

Are electric utilities overbuilding fossil fuel infrastructure to meet anticipated demand growth from data centers? There is certainly a growing possibility that while growth is on the way, it may not be as strong or come as soon as many utility companies currently project.

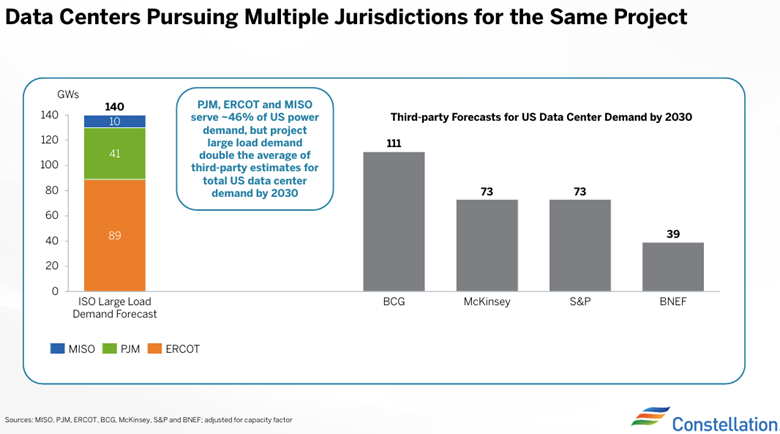

Earlier this month, the CEO of Constellation Energy, one of the nation’s largest independent power producers, issued a warning to investors about overbuilding. In the company’s first quarter 2025 earnings call, Joseph Dominguez pointed out that the utility industry’s projections for data center demand growth in just three markets—PJM (mid-Atlantic), MISO (Midwest) and ERCOT (Texas)—exceed many credible projections for data center demand growth for the entire country: “It's hard not to conclude that the headlines are inflated.”

James Burke, CEO of Vistra Energy, which bills itself as the U.S. largest independent power producer, delivered a similar caution during his company’s first quarter earnings call. Responding to an analyst’s question about Vistra’s somewhat cautionary take on future data center demand growth, Burke pointed out that many of the requests for power likely are duplicative: “We think these interconnect queues … may be overstated anywhere from three to five times what might actually materialize either in regulated markets or competitive markets.”

There is data backing up Burke’s concerns. In testimony this month on Georgia Power’s current long-term resource planning process, the staff of the Georgia Public Utilities Commission (PUC) showed that the utility has significantly overstated likely demand growth from new data center construction. In part, staff said this is due to the utility’s assumption that these projects are more likely to be constructed than more conventional large load facilities. The opposite is true, according to the PUC staff: “Data center projects exhibit a tendency to be cancelled at a higher rate than other projects. As such, these projects should be treated with greater uncertainty.”

Looking specifically at Georgia Power’s update to its 2023 integrated resource plan (IRP), staff pointed out that 44 percent of the data center-related growth it projected (5,445 megawatts (MW) out of 12,135 MW total) has been removed from the company’s estimates in just the past 18 months. The October 2023 IRP update essentially served as the starting point for the current wave of utility growth projections associated with new data center development across the country.

This same cancellation concern has been raised by Brian FitzSimons, the CEO of GridUnity, a company that helps utilities track and process large load power requests. He was quoted earlier this year saying that 30 percent of the proposals received by one of GridUnity’s large utility clients were canceled in 2024.

These warnings echo IEEFA’s January 2025 report, which found that data center demand growth is being used to justify a buildout of natural gas infrastructure across the Southeast. In that report, we noted that utility demand growth forecasts in four states (Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia) outstripped—in some cases by up to a factor of four —independent analysis of data center industry trends in those same states. Similarly, a December 2024 report from Grid Strategies found that nationally, the utility industry is planning for about 50% more data center demand than the tech industry is projecting.

Beyond the certainty of overcounting potential demand growth due to this multi-jurisdictional bidding process, there also still are major questions regarding the underlying business model for artificial intelligence and by extension, the need for all the data centers now in utilities’ demand forecasts. A January 2025 IEEFA report looked at the finances of OpenAI, a leading artificial intelligence company, and concluded that the company would have trouble growing its revenues to cover its high costs, due to the nature of its business model and the high energy and infrastructure costs required to develop and run its models. Although OpenAI to date has succeeded in raising ever-growing amounts of capital, there are signs that the artificial intelligence (AI) boom is slowing.

For instance, SoftBank, in charge of raising the $100 billion that the Stargate project announced in January that it would immediately deploy, has yet to sign any financing deals. SoftBank’s credit outlook was lowered to “negative” by the Japan Credit Rating Agency in April, specifically due to its deepening investments in AI, which S&P also describe as a "creditworthiness headwind."

Similarly, over the past year, Microsoft has shifted from warning about a shortage of data centers for AI to stating that data center capacity will be overbuilt. Joe Tsai, chairman of Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce conglomerate, echoed that concern at a March conference. “I start to see the beginning of some kind of bubble,” he said. “I start to get worried when people are building data centers on spec.”

Constellation’s Dominguez did not use the term bubble in his remarks, but he did offer a strong cautionary note about the projected AI and data center demand growth in his remarks on the company’s Q1 earnings call. “But to be fair, some of the hyperbole about the size of the growth is coming from stakeholders who have their own motivations, including a desire to keep building out the wire system or competitive market utilities that simply want the right or permission to go back and build generation in a competitive market. We've been seeing that in a few places. But we also see policymakers becoming skeptical about these claims. That skepticism is warranted in our view.”

That skepticism is warranted in IEEFA’s view as well. If electric utilities build infrastructure—transmission lines, power plants and gas pipelines—to meet data center demand that does not materialize at the levels they anticipate, they likely will be stuck with significant stranded costs. Those stranded costs, in the absence of strong regulatory action, will be passed on to the utilities’ existing electricity consumers. They also will have spent billions of dollars on fossil fuel infrastructure that could have been better spent to further the energy transition.