Pro-coal arguments in ASEAN are based on false assumptions and unproven solutions

Key Findings

Recent arguments claiming that phasing out coal would compromise Southeast Asia’s energy security are misconceived. Energy systems reliant on coal are not inherently secure as commodity market fluctuations challenge affordability during global energy disruptions, reducing energy security.

Members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) with coal-dependent power systems were significantly impacted when global coal prices trebled in 2022. Higher fuel costs led to operating losses for utilities and put upward pressure on electricity prices.

Current solar and wind capacity in ASEAN is too low to meaningfully impact system reliability. System operations are likely to be only negligibly impacted if capacity is tripled this decade, and moderately impacted if capacity increases six-fold.

Softening regional climate ambitions based on pro-coal narratives would only prolong the region's exposure to volatile commodity markets, obstruct capital flows toward clean energy, and prevent countries from realizing the economic benefits of the energy transition.

In recent months, there has been an increase in arguments from skeptics suggesting that coal should continue to play a significant role in Southeast Asia's energy mix. They contend that phasing out coal would compromise the energy security, reliability, affordability, and sustainability of the region’s power generation.

However, these critiques are based on misconceptions that overstate coal as a secure energy source and mistakenly associate renewables deployment with grid instability. Consequently, they draw the misguided conclusion that coal should remain a key energy source, supported by unproven technologies like carbon capture and ammonia co-firing.

Ultimately, these assertions only serve to delay the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)’s transition from coal, hinder financing for real climate solutions, and prevent countries from capturing the economic benefits of renewable energy.

Recent market disruptions challenge energy security narratives

Energy systems reliant on coal are not inherently secure. The fluctuations of commodity markets can challenge affordability during global energy disruptions, reducing energy security. ASEAN countries should be well aware of this as the region’s electricity sector was not spared from volatility during the recent energy crisis despite abundant cheap coal supplies.

As global coal prices trebled in 2022, members with coal-dependent power systems were especially impacted. In Vietnam, a quadrupling of coal import prices pushed the operating cost of electricity beyond the retail tariff, resulting in a VNĐ31 trillion (US$1.2 billion) loss for the national utility. In the Philippines, the cost of generation for key coal power plants doubled and has yet to revert to pre-crisis levels. Since 2021, the Manila Electric Company (Meralco)’s electricity tariffs have risen from PHP8.75 to PHP11.60 (US$0.15 to US$0.20) per kilowatt-hour. In Cambodia, rising coal costs have halted a tariff reduction plan that began in 2015.

These impacts persist. At US$144 per tonne, coal benchmarks remain well above their ten-year average of US$83 per tonne before the crisis.

Coal proponents have argued that liquefied natural gas (LNG) poses risks to energy security and price stability, overlooking the fact that coal faces the same pitfalls. This vulnerability will worsen as ASEAN becomes a net coal importer in the next decade.

Fortunately, the region can chart a more secure energy future by integrating additional renewables into the power system, initiating a phase-down of coal and reducing this vulnerability.

Substantial opportunity for renewables deployment without compromising grid reliability

Relevant stakeholders should consider the impact of wind and solar penetration on the performance of national grids. However, the share of penetration across ASEAN member states is too low to impact system operations meaningfully.

The International Energy Agency classifies countries into six phases based on the share of solar and wind in their electricity mix and other grid-specific characteristics. Phase 1 corresponds to a share of roughly under 5%, Phase 2 ranges from around 5% to 15%, and Phase 3 ranges from around 15% to 25%. Phase 1 represents a level where the solar and wind share has no relevant impact on the power system, Phase 2 only has minor impacts, and higher phases present greater challenges.

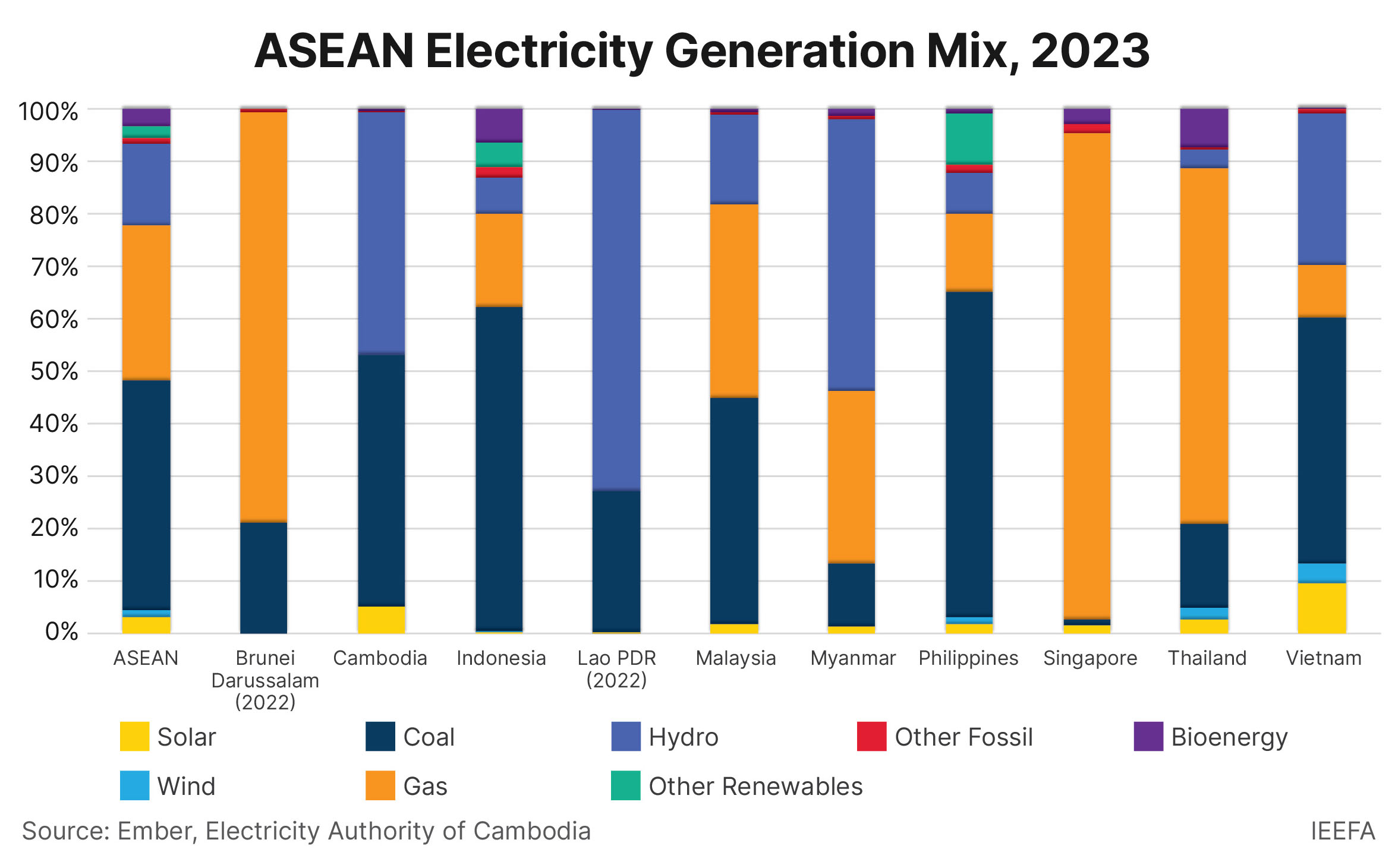

Charting the power mix across ASEAN illustrates that most countries are in Phase 1 of renewable energy integration, except for Vietnam, which is in Phase 3. This indicates that the limited solar and wind deployment across the region has not yet significantly impacted power system operations. It also suggests there is a substantial opportunity to increase renewable capacity without compromising electrical reliability.

The Baseline Scenario of the 7th ASEAN Energy Outlook projects that ASEAN will require 1,630 terawatt-hours (TWh) of generation by 2030. According to the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), a tripling of the region’s existing solar and wind capacity, operating at current capacity factors, could enable solar and wind to meet over 10%, or 163 TWh, of this requirement. This would result in a Phase 2 classification, indicating minor impacts on power system operations. Even a sixfold increase to over 20% (326 TWh) suggests moderate system impacts, corresponding to Phase 3.

Accelerating the adoption of renewable energy will require supportive policies from ASEAN member governments. While recent reforms in Vietnam are encouraging, significant policy barriers to scaling renewables remain, particularly in Indonesia. Favorable policies that enhance the bankability of renewables will be integral to phasing out coal across the region.

Phasing out coal with renewables will improve energy security and grid reliability

Recent commentaries supporting coal usage in ASEAN suggest that the “immediate retirement” of coal plants would jeopardize the region’s energy security. They argue that “phasing down” coal is more appropriate than “phasing out” coal, and that unproven transition technologies — including carbon capture and ammonia co-firing — should qualify for sustainable finance.

However, these arguments present a false dichotomy. The reality is that rapid adoption of renewables will reduce the need for coal over time, improve energy security, and lower electricity prices. Coal retirement mechanisms are designed to shorten coal plant lifetimes and replace them with clean energy, not shutter them overnight. Transition periods provide ample time to add renewable capacity, build complementary storage, and evolve grid operating protocols. Delaying will only compress these essential tasks into a more challenging timeframe. Ambitious language in taxonomies emphasizing the need to “phase out” coal is designed to stimulate investment flows in real solutions and reduce capital costs for proven technologies.

Softening regional climate ambitions based on pro-coal narratives would only prolong the region’s exposure to volatile commodity markets, obstruct capital flows toward clean energy, and prevent countries from realizing the economic benefits of the energy transition.