Nuclear reactor problems in France show need for diversified mix of renewables

As heatwaves hit French nuclear output, renewables-reliant Sweden comes to Europe’s rescue

It should come as no great surprise that France, traditionally a leading exporter of electricity to the rest of Europe, is now in the position of needing to import power. A summer marked by severe and persistent heatwaves and prolonged drought, plus shutdowns of more than half its nuclear fleet for routine and emergency maintenance, have sent electricity prices skyrocketing and reduced the country’s ability to generate surplus amounts of power.

Lost in the hubbub over supplier issues, however, is the fact that the country replacing France as the continent’s leading exporter of electricity – Sweden – has been reducing its reliance on nuclear power to produce electricity.

The shift underscores two realities: Nuclear power, hailed as the most reliable source of electricity since the first plant went online in 1951, is likely to become less reliable as climate change causes more extreme weather events, such as extended heat waves, droughts, and floods. And a mix of renewable energy sources, such as the one being used by Sweden, will be crucial to keeping the lights on as the transition away from a carbon-based economy picks up speed.

France relies more on nuclear power than any other country on the planet. Its fleet of nuclear plants provided 66.5 percent of the country’s electricity in 2020. Over the past decade, France has exported 70 terawatt-hours of electricity every year.

Recurring heat waves and drought, however, have complicated an already fraught situation. Roughly half of French nuclear plants were scheduled for routine maintenance or needed repairs at the beginning of the summer. Corrosion discovered on one reactor’s pipes led to the closure of at least a dozen more; about half of its reactors were closed by mid-July. Demand rose as temperatures soared. Meanwhile, the remaining nuclear plants – which use water for cooling and then return the hot water into rivers and lakes – were in danger of violating rules designed to keep the hot water from damaging fragile marine environments.

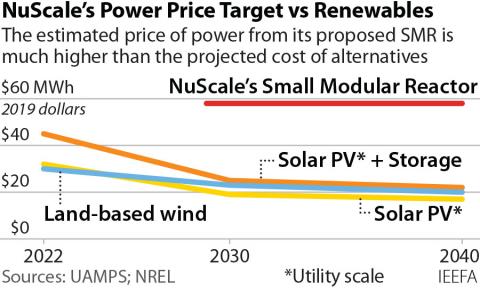

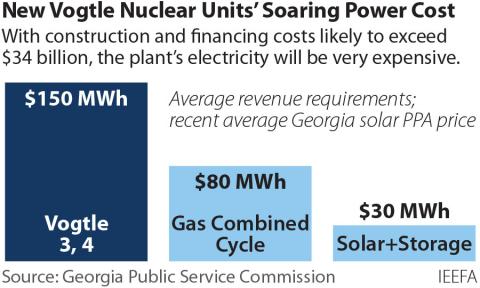

France proposes to solve the problem by building more nuclear plants, focusing on small modular reactors (SMRs) and European Pressurized Reactors (EPRs). The EPRs use pressurized water to create steam and spin the turbines; SMRs use thermal energy to covert water into steam that spins the turbines . Unfortunately, neither SMRs nor EPRs are practical solutions. SMRs in particular are an unproven technology at scale that will cost too much, arrive too late, and not be reliable enough to ensure a smooth transition to a carbon-free economy.

EPRs have suffered from other issues. The French utility giant EDF, a co-designer of the EPR that’s being taken over by the government, has acknowledged issues with the technology; the first reactor, built in Finland, is expected to begin operation in December after a 13-year delay caused by design problems, lawsuits, and construction mistakes. The Olkiluoto 3 (OL3) plant has been described as a “cautionary tale” for countries considering more nuclear power.

Small modular reactors are hardly more promising. The technology has not been fully developed, there are no commercially operating SMRs on the planet, and the U.S. Department of Energy estimates an SMR designed by NuScale will cost $6,800 per kilowatt, more than double the designer’s estimates. In addition, the SMR wouldn’t generate electricity until mid-2029, at the earliest. A February IEEFA report described the reactor as “too late, too expensive, too risky, and too uncertain.”

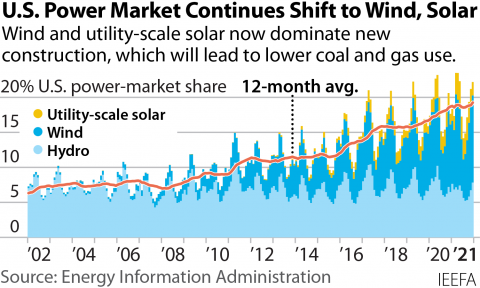

Sweden, which ascended to the position of top exporter of electricity in Europe for the first six months of 2022, has been curbing its reliance on nuclear power. The Nordic country’s nuclear fleet accounted for 30.1 percent of its total energy supply in 2020, down from 46.5 percent in 1990, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). Renewables made up 68.5 percent of Sweden’s electricity sources in 2020.

What’s more, Sweden has a diverse mix of renewables. Hydroelectric power generation has fallen more than 5 percent since 1990, and currently makes up 44.2 percent of the country’s electricity sources. Wind is the third-largest source, trailing nuclear at 30.1 percent but rapidly narrowing the gap. Wind accounted for 2.3 percent of the Swedish electricity mix in 2010; the figure had risen to 16.9 percent by 2020. Biofuel generation has risen to 4.7 percent, and electricity generated from waste makes up 2.1 percent of its power mix. Even solar, which faces significant obstacles at high northern latitudes, is chipping in with 0.6 percent of generation. Meanwhile, coal, oil, and natural gas only made up 1.4 percent of electricity generation.

The situation is somewhat analogous to the heat wave that baked Texas this summer. If the state had relied on its primary source of power (in this case, natural gas) to the extent that France relies on nuclear power, widespread outages and heat-related deaths amid the triple-digit temperatures would have been possible. But since Texas had a diverse mixture of resources to generate electricity – solar and wind each generated more than 10 percent of peak demand for more than two-thirds of July –disaster was averted.

The lessons of the heatwave in Europe should be clear: A diverse mix of renewable energy sources is the best option for ensuring a smoother energy transition, and unaffordable, unreliable or unproven sources of electricity won’t help matters.