IEEFA U.S.: Why exports won’t save American coal

Data published last week by S&P Global Market Intelligence shows U.S. coal exports fell by 28.1% in the fourth quarter of 2019 compared to the fourth quarter of 2018.

Data published last week by S&P Global Market Intelligence shows U.S. coal exports fell by 28.1% in the fourth quarter of 2019 compared to the fourth quarter of 2018.

That headline number was underscored by an S&P estimate that exports from the Illinois Basin (Illinois, Indiana and western Kentucky) had fallen by 58.7% year-over-year, a figure based on the sharp drop in tonnage through the Port of New Orleans, which handles nearly all of the coal coming out of the basin. Production in the Illinois Basin has tanked so far this year, down 18.6% through February 22 compared to the same time in 2019, and the basin faces serious long-term obstacles to any sustained recovery (see the IEEFA report Dim Future for Illinois Basin Coal from December).

The problem is not limited to Illinois Basin coal, however. Overall, coal exports through other key U.S. ports dropped sharply too. Year-over-year numbers for the top five coal-export ports, from S&P by volume of traffic: -21.5% at Norfolk; -12.9% at Baltimore; -27% at Mobile; -68.7% at New Orleans; and -12.7% at Seattle.

Coal companies have been touting exports as a way to offset deteriorating domestic markets

As domestic thermal coal consumption for electricity generation has declined, coal companies have been touting exports as a way to offset deteriorating domestic markets. Companies like Contura Energy and Murray Energy, for instance, have made significant investments in metallurgical coal, arguing that its global market— though miniscule compared to thermal coal—will support higher and steadier profits (metallurgical coal is used in steelmaking, thermal coal is for power plants).

Contura Energy exemplifies this strategy. The company was created in 2016 by top lenders to the bankrupt Alpha Natural Resources, taking what were seen at the time as the company’s most desirable “core assets,” including two big Powder River Basin thermal coal mines. The remaining assets, seen as less desirable, went to unsecured creditors as a restructured Alpha Natural Resources. A mere 18 months later, in December 2017, Contura changed its approach and dumped the Powder River Basin mines, essentially giving them to a new company, called Blackjewel, for “deferred consideration.” Then, in April 2018, Contura announced yet another shift: It would merge back with Alpha and become primarily a metallurgical coal company.

Just as the merger was completed, in November 2018, export prices for metallurgical coal began to sag, hitting a three-year low by the beginning of 2020. Contura’s stock price has followed, tumbling 90% over the past year.

U.S. COAL EXPORTS HAVE ALWAYS BEEN UP AND DOWN, DRIVEN BY VOLATILE GLOBAL PRICES, which see-sawed from 2000-2012 but generally trended up, allowing U.S. producers to fill a swing-market role more or less in step with prices. Exports rose to about 37.5 million tons (thermal and metallurgical) in the second quarter of 2012. Demand then declined sharply, falling to 12.5 million tons in the third quarter of 2016 before gaining some traction through 2018, then falling. The Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that exports will total something south of 8 million tons in the last quarter of this year.

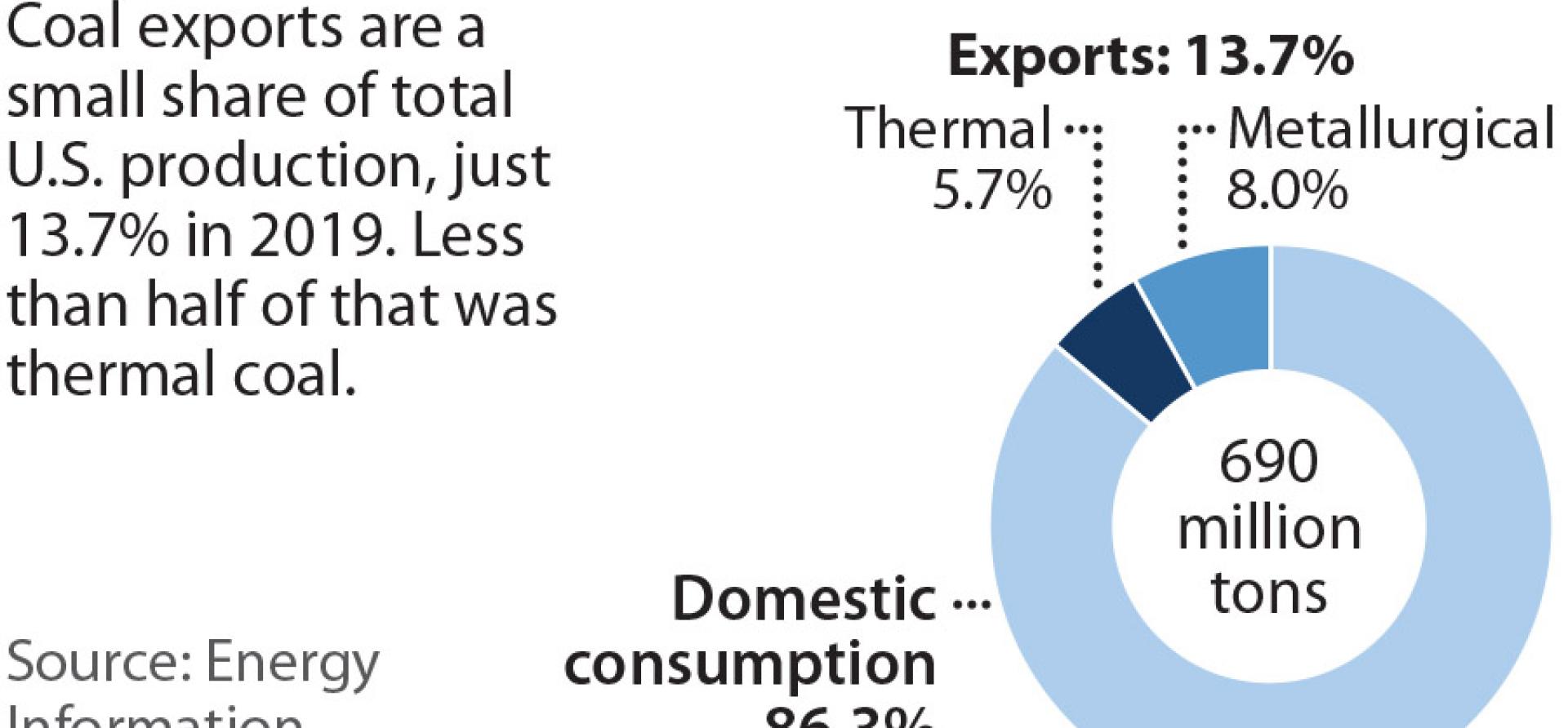

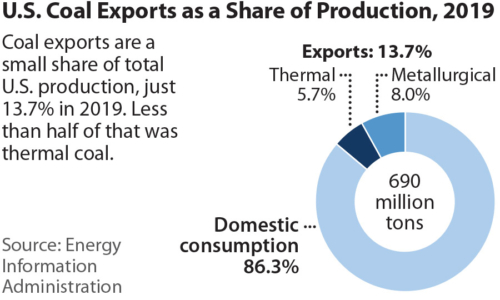

Overall, coal exports have accounted for a relatively small part of all U.S. production, averaging just 11% over the past five years, so it would be challenging in the best of circumstances for exports to make up for the huge decline in domestic consumption.

Europe is moving away from coal, and Asia is moving in a similar direction

Europe is getting off coal, and Asian players are moving in that direction as well. The EIA ranks the five biggest export-market countries for U.S. coal as India, the Netherlands, Japan, South Korea, and Brazil. They now total 50% of all demand for U.S. coal, and—because of market forces and policy decisions—none is likely to want to keep buying at anywhere near the same levels as before.

THE METALLURGICAL SLIVER OF THE COAL EXPORT MARKET IS PROBLEMATIC TOO. Transoceanic shipment makes up a significant part of the delivery price and is a major competitive barrier for U.S. producers when prices are low. Steel markets also fluctuate with economic cycles, adding to rather than mitigating financial risks for mining companies.

To stakeholders in U.S. majors like Arch Coal, Contura, Peabody Energy, Murray and Navajo Transitional Energy Company (NTEC), export trends are every bit as unsettling as domestic-consumption ones. As Contura’s stock price has cratered, so has Arch’s, down 45% over the past year (to less than $51 per share from over $93), and Peabody’s, down 82% (to less than $5.50 from almost $32). Murray and NTEC aren’t publicly traded, but Murray filed for bankruptcy last October, and NTEC is a black box even to its owner, Navajo Nation, although it is so financially challenged that it has resorted to installment plans to pay the taxes and royalties it owes on the three big coal mines in Montana and Wyoming purchased last year from the now-bankrupt Cloud Peak Energy.

Analysts at Morgan Stanley have articulated the domestic problem about as clearly as it can be stated. The most recent research report, published last week, says U.S. utility companies would be wise to close uneconomic coal plants, take the money saved, and put $64 billion into cheaper renewables over the next five years. In another report, published in December, analysts have market forces driving the retirement of up to 190 gigawatts, or nearly 85% of all remaining coal-fired generation capacity in the U.S., by 2030.

The collapsing domestic market is why the industry continues to talk up exports as a panacea, despite exports accounting for less than 14% of all U.S. coal sales last year (mostly metallurgical); and ignoring the fact that these markets are unreliable to begin with; and that shifting global energy preferences suggest demand from abroad won’t bring fundamental or lasting relief to the American coal industry.

Related items:

IEEFA U.S.: Navajo-owned energy company is in trouble

IEEFA U.S.: The coal rebound that didn’t happen

IEEFA update: Data shows U.S. shift away from coal-fired generation is intensifying