BHP Coal – from cash cow to capital trap?

Key Findings

BHP has an enviable track record of capital management, but returns are being depressed by its coal division, raising questions over whether further coal expansions would be a sound business decision.

Despite the company placing a focus on the impact of royalties, increases in production costs – in particular labour costs – have directly contributed to putting its margins under pressure.

Recent mine closures demonstrate the undesirable practice of placing an unviable mine into indefinite care-and-maintenance mode. BHP has the lowest rate of rehabilitation completion within the sector, but expediting rehabilitation represents an opportunity to show leadership and create a new industry.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

BHP’s Queensland coal operations seem to have transitioned from cash cow to capital trap, generating 2.2% of company earnings and producing marginal capital returns.

In FY2025, it reported a return on capital employed (ROCE) of 1% for BHP Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA), compared with 20.6% for the wider BHP group. EBITDA [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation] margin for BMA was 17%, about half that of FY2024 and a third of the group’s 53% EBITDA margin in FY2025.

BHP has been systematically shedding coal mines to “focus on producing higher quality metallurgical coal sought after by global steelmakers to help increase efficiency and lower emissions”. Equity coal sales production has fallen 58% over 10 years to 17.8 million tonnes (Mt) in FY2025, as the company has halved the number of mines in its portfolio to five. However, this consolidation has not helped increase returns.

BMA has been battling an ever-increasing unit cost base, which grew a further 7% in FY2025 to US$127.50 per tonne (Figure 1). Unit costs have been impacted by declining volumes as fixed costs, overheads and capital are socialised across fewer tonnes. Unit costs also continue to be affected by labour shortages in the industry, and are yet to fully reflect the new contractor pay rates. In July this year, BHP was ordered to pay an average annual increase of AU$30,000 to some 2,200 coalminers, under “same job same pay“ legislation. BHP has sought to challenge the decision in the Federal Court of Australia.

Meanwhile, royalties paid fell by 47% due to lower coal prices. Despite industry claims that Queensland has “the world’s highest coal royalty regime”, the 40% top marginal rate does not apply now that coal prices have fallen to below US$200 per tonne (less than AU$300 per tonne). According to calculations by Argus, the new royalty rate for hard coking coal is 4% higher (at 16%) than under the old regime.

Figure 1: BHP Queensland coal’s unit cost 10-year trend

With capital returns from the coal division so low, it raises the risk of potential asset devaluation. BHP took a US$1.7 billion impairment charge at its Mount Arthur thermal coalmine in FY2021. Could the company be similarly reassessing its metallurgical (met) coal assets?

Is further growth of BHP’s coal business a good use of capital?

Last week BHP received media praise for having “the most disciplined capital allocation among global majors” through strategic portfolio decisions.

Last year’s failed takeover bid for Anglo American, abandoned after multiple offers were rejected, may prove to be fortuitous. A month later, in June 2024, Anglo’s Grosvenor underground coalmine was closed due to a methane fire, followed by a similar incident at its Moranbah North underground mine in March this year. Both mines remain closed.

Methane incidents create cascading costs: lost production value; continuing employment costs during outages; equipment replacement; re-entry expenses; and increased regulatory compliance. While BMA operates one underground mine, at Broadmeadow, adding Anglo’s assets would have intensified these structural risks.

BHP currently seeks to extend its Peak Downs mine by 93 years to 2116, extracting a further 1.256 billion tonnes of coal. Recent results raise questions on the whether this is the best place for BHP to invest its capital.

Pushing back rehabilitation liabilities

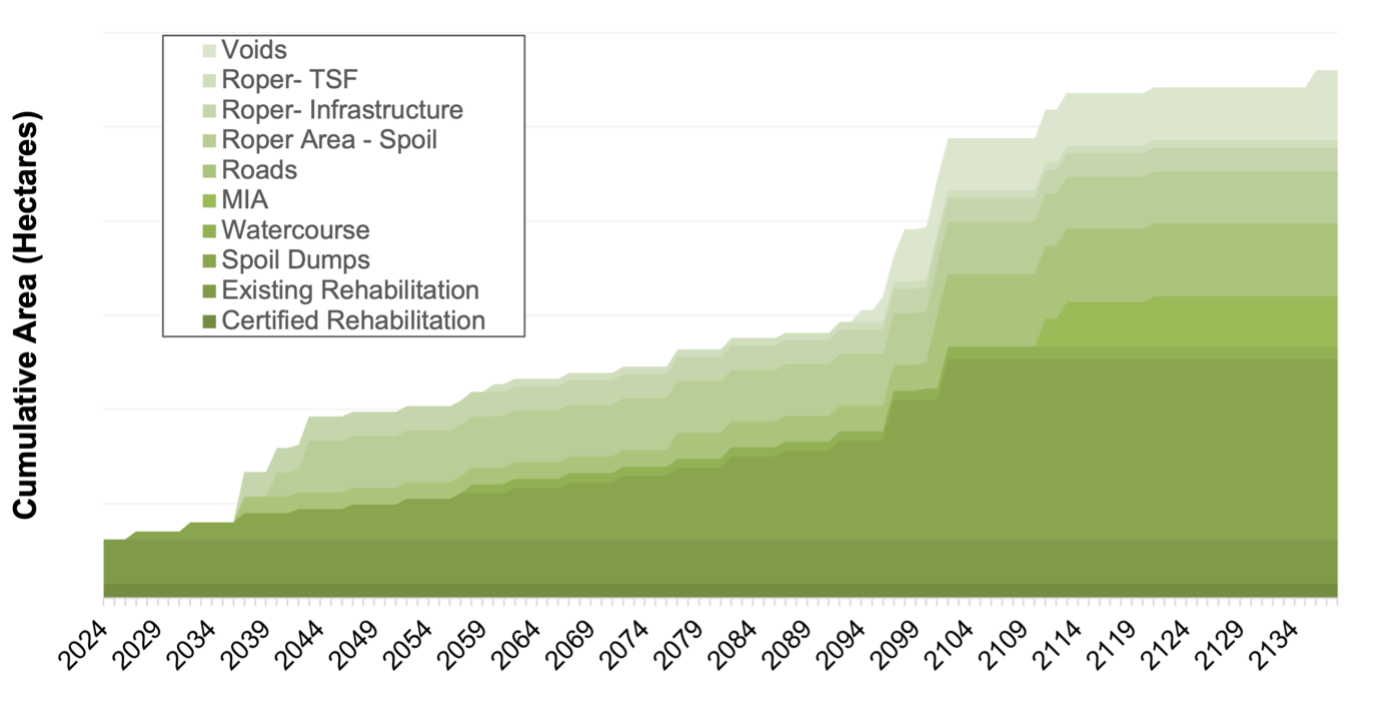

In September, BMA announced its Saraji South mine would be mothballed from next month. Saraji South mine extends over some 25km and sits at the end of BHP’s approximately 100km of open-cut mining strip in Queensland’s Bowen Basin. The rehabilitation plan for the site was finalised last month. It provides for progressive rehabilitation to be completed over more than 100 years, with just over half of the area rehabilitated by the end of this century (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Saraji South mine progressive rehabilitation

Source: Progressive Rehabilitation and Closure Plan. Saraji South Mine (Norwich Park Mine), 26 September 2025), Landform development and reshaping milestones. BMA.

As explained by BHP’s chair, when mines are placed in care and maintenance, “they may be opened up at a later stage, if the pricing changes, or we can find different ways of using those resources and making them economic.” However, these reopenings can be very short-lived, repeating the lay-off of workers when prices fall. IEEFA has found that coalmines recently marked for closure in Queensland share one thing in common: they are all previously mothballed mines that were shut on the grounds of being uneconomic. Most of those mines were only reopened for 1-4 years. BHP considers that medium-term demand for its coking coal is strong, but will that be sufficient to reopen a high strip-ratio mine for a long period of time?

In IEEFA’s view, a responsible approach to asset management would be to permanently close the mine and expedite its full rehabilitation. This would provide ongoing employment opportunities for displaced workers. Rather than viewing rehabilitation as a cost burden, accelerating progressive rehabilitation could itself become an industry that sustains regional employment. Given the deteriorating outlook for Australian metallurgical coal exports, prioritising rehabilitation investment – not reducing royalties – could be a more effective way to secure jobs, investment and prosperity in regional Queensland.

Expediting closure and rehabilitation is unlikely to be financially attractive to BHP. Permanent closure of Saraji South would likely indicate an asset impairment charge and potential removal of reported coal reserves, if they are declared no longer economically viable.

This is the start of a much larger problem for BHP. BMA mines have the largest footprint of disturbed land remaining to be rehabilitated – with more than 40,000 hectares of coalmine land, according to annual rehabilitation returns. BHP’s rate of mine rehabilitation completion, at 7% of disturbed mining area, is the lowest within the sector. The statewide coal mine range varies from a lowest of 7% to a highest of 52%, with an average of 25%, according to the 2024-25 Queensland Mine Rehabilitation Commissioner Annual Report.

When BHP’s Mount Arthur mine closes in 2030, it will complete the company’s phase-out of thermal coal. BHP’s Queensland metallurgical coal operations have shrunk to the point of insignificance in their contribution to the company’s overall profits and return on capital. BHP’s CEO has flagged “more difficult decisions” may need to be made, unless changes are made to royalties and taxes.

However, in IEEFA’s opinion, such changes would be unlikely to offset the impact of high production costs in a depressed coal market. Adding in substantial rehabilitation liabilities and operational risks, this raises “difficult decisions” of whether further growth is a sound investment decision for the company.