IEEFA U.S.: A rough week for the American coal industry

The economic problems facing the U.S. coal industry have been on manifest display this week.

On Tuesday morning, the federal Energy Information Administration reported that coal use in the U.S. is on track to fall to its lowest level since 1979, and that by year’s end consumption will be 44% below the 2007 peak of 1,128 million tons.

A few hours later, Xcel Energy announced plans to be carbon-free by 2050, a policy that will require the closure of the utility’s 19 coal-burning units that have a total capacity of just under 7,000 megawatts.

That same afternoon, S&P Global Market Intelligence published an article citing analyst warnings that the one current bright spot for the U.S. coal sector, rising exports, likely will soon fade, held in check by slowing global growth.

Bad signs for coal generators across the country.

Consequential as those developments are, the week’s real kicker was the news that utility giant PacifiCorp has concluded that most of its 22 coal-fired generation units are no longer economically competitive and that, in essence, it would make financial sense to shut many of its existing coal-fired plants and build/buy new generation to replace that lost capacity.

PacifiCorp is a sprawling utility that sells power to almost two million customers in six western states (California, Idaho, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming). Its concession that so much of its coal fleet is no longer economic came out by way of documents prepared for its upcoming 2019 integrated resource plan for the state of Oregon. The IRP process has been contentious and closely watched; this week’s briefing by the company shows why.

In its analysis, which was mandated by Oregon regulators, PacifiCorp began by conducting a unit-by-unit review of its coal plants that found 13 of 22 facilities could be replaced with cheaper alternatives, using 2022 as the hypothetical retirement date (the utility did not include its Naughton 3 coal unit in southwest Wyoming in its analysis because the facility is due already to close by the end of January).

The results of its review, PacifiCorp stressed, are not final and do not suggest any preferred course of action. Still, it’s a clear indicator of the headwinds facing coal generation.

Beyond its individual unit analysis, PacifiCorp also conducted some stacked assessments around the costs/benefits of retiring a group of plants at the same time—and here the results get really problematic for coal.

In one of these assessments, PacifiCorp studied the possibility of a group retirement of five units in 2022. The units in question, which have a total capacity of 834MW: Naughton 1&2, Hayden 1 and Craig 2 in northwest Colorado, and Jim Bridger 1 in southwest Wyoming.

While PacifiCorp in this analysis plays up what it says is the need for further study, particularly on potential new system reliability costs as a result of the joint closings, the company says that shuttering these five units would provide a benefit of $317 million as measured by its present value revenue requirement—or a nominal levelized $43.13 per megawatt-hour of retired capacity.

WHAT’S SO DAMNING ABOUT THIS ASSESSMENT IS THAT THE FIVE UNITS REVIEWED are some of the best performers in the PacifiCorp system.

Overall, the company’s 10 coal-fired plants, which have a combined 22 separate generation units with a total of just under 6,000MW of generation potential, posted a capacity factor of almost 69% in 2017, according to S&P data.

The five units in this stacked-retirement assessment have been near or above that mark for years:

- Hayden 1 posted a 75.8% capacity factor in 2017 and was well above 80% in 2013 and 2014.

- Naughton 1 notched an 81.1% mark in 2017 and recorded a capacity factor of more than 90% in 2013, 2015 and 2016.

- Naughton 2’s capacity factor has been above 80% every year since 2012.

- Craig 2’s capacity factor was only 60% in 2017 due to a two-month outage, but was over 70% during the six years prior and is on track to be above 70% in 2018.

- Jim Bridger 1 posted a 2017 capacity factor of 63.3%, but the unit recorded a six-year average prior to that of 73.7%.

In short, these are not poorly performing plants, and yet they are not competitive, according to PacifiCorp’s own analysis.

The reasons these plants are losing the battle for market share are well known: Readily available supplies of low-cost natural gas and the surging interest in and rapidly declining costs of renewable energy, particularly wind and solar but also, increasingly, hybrid combinations that include battery storage.

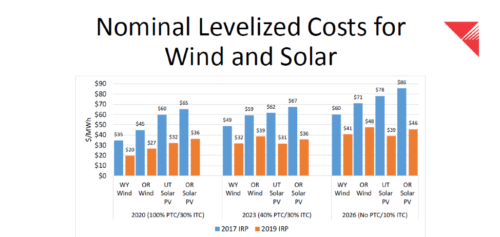

What’s often overlooked here is the speed of the transition, clearly evident in the PacifiCorp graphic below that shows sharp declines in state-by-state trends in wind- and utility-scale solar generation.

The economic forces that continue to build against coal have strengthened significantly recently and show no signs of abating. These are bad signs not just for PacifiCorp’s coal assets but for coal generators across the country.

Dennis Wamsted ([email protected]) is an IEEFA editor.

Related items:

IEEFA U.S.: Transition to renewables has taken hold in historically coal-dependent northern Indiana

IEEFA report: ‘Holy Grail’ of carbon capture continues to elude coal industry; ‘cautionary tale’ applies to domestic and foreign projects alike