IEEFA U.S.: Coal inventories are down at utilities, yes, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be replenished

The U.S. coal industry’s third quarter earnings reports are out, and one theme is repeated over and over again: Utility-coal inventories are low, which—according to producers—will boost domestic thermal sales going forward.

Arch Coal, for example, points out that domestic utility inventories are currently “at the lowest level in four years in terms of days of supply.” Peabody Energy strikes a similar tone, noting that utility stockpiles are now down to approximately 100 million tons, “the lowest levels since 2005.” Consol Energy notes that as of August 2018, utility coal inventories were down approximately 26% from a year ago, to “the lowest level since the end of 2005.”

All of these reports have an implicit note of optimism—if inventories are so depressed, utility companies will surely be seeking to replenish them.

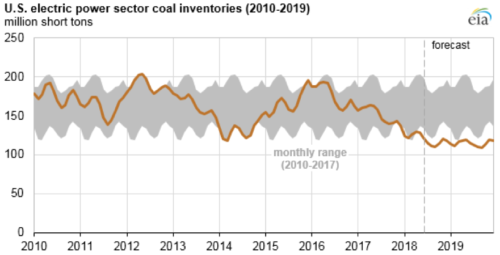

As the graphic below from the Energy Information Administration shows, coal companies have a point in one respect: Inventories are down (the line represents the average total, the shaded area reflects monthly ranges). But that’s not to say this is good news for coal producers.

For starters, from 2015-2017 almost 30,000 megawatts of coal-fired capacity were retired, This year more than 11 gigawatts of have been shut down, and more retirements are on the way. Put another way, inventory requirements are nowhere near what they used to be.

In many cases coal units like Duke Energy’s Mayo and Roxboro plants in North Carolina are now being run as intermediate rather than baseload units, ramping up and down to match changes in solar and/or wind output as well as natural gas generation. Those two plants were true baseload generators in the 2000s, posting capacity factors of 69.5 percent and 67.3 percent, respectively, from 2000-2010. Since then, their usage, and consequently their need for large coal inventories has been declining. Similar changes are occurring across the U.S., particularly in wind-rich Midwest and Plains states, where coal increasingly is being pushed out of its former baseload generation position.

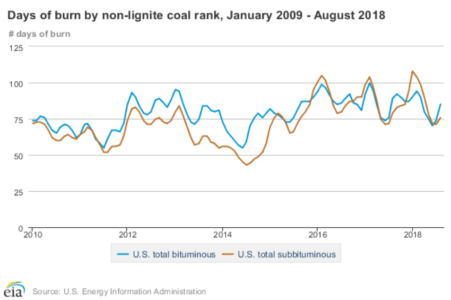

Given these trends, a much more realistic measure of coal plant inventory levels is what EIA dubs its “days of burn” analysis. Instead of just tracking tons of coal on hand, this analysis uses plant generation data from the past three years and extrapolates forward to estimate how long a plant can operate if no more coal is supplied to the facility. Using this approach, as the graphic below illustrates, utility coal inventories—currently at roughly 75 days—are completely in line with requirements going back to at least 2010.

Given rapid changes in coal plant operations, effective inventory levels might even be higher than EIA calculates, since the agency is relying on generation statistics that may no longer be valid. Duke’s Mayo plant serves as a good example again. In 2015, it posted a capacity factor of 44.5%, and in 2017 came in at just under 22%. In other words, even this EIA analysis likely understates the “days of burn” at Mayo and probably at similar coal plants nationally too. Such plants are simply not being operated in the same way they were in years past, even in the recent past.

IEEFA SEES A RECORD 15.2GW OF COAL-FIRED CAPACITY RETIRING THIS YEAR, and estimates that at least 17GW of additional coal capacity will go offline through 2022, a trend that will further decrease domestic coal demand.

Coupled with the changing operating environment for many coal plants—forthcoming IEEFA research will explore this issue in greater detail, but it’s worth noting here that the capacity factor at each of the 23 largest coal-fired power plants in the U.S. declined from 2010-2017—gross inventories will likely never return to their past “normal.”

The question is whether coal producers will acknowledge these fundamental market changes or simply continue telling investors that inventories are low and insisting that sooner or later utilities will start buying more coal again. Judging by the tone of their third quarter reports, coal industry executives are still looking backward while utilities continue to move forward.

Dennis Wamsted is an IEEFA editor.

Related items:

IEEFA report: U.S. likely to end 2018 with record decline in coal-fired capacity

IEEFA update: Another Texas coal-plant closing, another market signal