Turkey is right to seek to diversify from imported natural gas, seeking indigenous energy alternatives, but so far has missed an important part of the answer in solar power.

Turkey is right to seek to diversify from imported natural gas, seeking indigenous energy alternatives, but so far has missed an important part of the answer in solar power.

That may about to change, with the award of a power purchase agreement for a plant of up to 1,000 megawatts (MW) – which would be one of the world’s biggest – on condition of investment in local manufacturing capacity and R&D. The plant, to be located in Karapınar in Central Anatolia, would be s $1.3 billion project.

Turkey is highly dependent on imported Russian and Iranian gas for power generation, and has limited gas storage capacity, leading to worries over brownouts or blackouts in the event of interrupted pipelines.

In a speech last month, Energy and Natural Resources Minister Berat Albayrak told Turkish Petroleum that northern Turkey must exploit far more of its indigenous coal and lignite, to assure security of supply and drive growth.

He calculated that Turkey had exploited a much smaller portion of its coal reserves, at 12-13%, compared with Europe, at 40-50%, for example.

But a starker contrast can be drawn with solar power.

Southwest Turkey has some of the best solar resources in Europe. The sunniest locations on the southwest coast receive a maximum solar energy, called direct normal irradiance (DNI), of about 7 kWh per square metre per day, NASA data show. The only comparable location in Europe is Cadiz in southwest Spain. At around 4.5 kWh per square metre, even northern Turkey is still on a par with Europe’s other leading solar hot-spots, Spain, Italy and Greece.

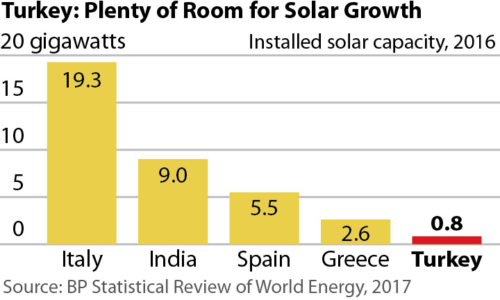

But Turkey is exploiting far less of this resource. As of last year, Italy had 19,279 megawatts (MW) solar PV installed, Spain 5,490 MW, Greece 2,611 MW, and Turkey just 832 MW, BP data show.

To take a page from a more comparable, rapidly Growing, economy, Turkey might look east to India, which has equivalent solar resources.

India’s energy minister, Piyush Goyal, has won plaudits for developing bankable solar park projects, trebling installed capacity in the past two years, to 9,010 MW in 2016, from 3,062 MW in 2014. That bankability has also seen rapid cost reductions, with tariffs falling to a new record low in May of $0.038/ kWh, below the cost of imported, and even domestic Indian, coal.

That is far more competitive than Turkey’s latest solar tender, where the successful bid was €0.07 per kWh. But Turkey can see similar, further cost reductions, if it assures investors of the reliability and stability of its new tariff program.

Gerard Wynn is a London-based IEEFA energy finance analyst.