IEEFA Update: Are Investors in Asian Coal Starting to Think Twice?

Human nature is to juggle contradiction and remain hopeful in the face of adversity. But investors are supposed to be hard-eyed cynics.

What, then, to make of financial professionals smart enough to pose shrewd questions about the impact of climate change on the coal industry but willing to settle for illogically incomplete answers?

This is the thought that came to mind during a recent private presentation by industry analysts aimed at fixed-income investors in Asian coal producers. Coal prices, after rebounding sharply in late 2016, have been volatile, but producers have benefited as higher prices have helped them rebuild cash positions and repair injured balance sheets. The sensible question for fixed-income investors now is whether the outlook for Asian coal is good enough to support a new round of debt financing for producers.

Here’s where the sometimes irrational characteristics of the investment world come into play. During the presentation noted above, which focused narrowly on the supply and demand balance for coal in China, Indonesia, and India over the next 18 months, the main query from the investor audience wasn’t whether the current outlook for coal is good, but what impact the Paris climate-change accords would have in restraining future demand.

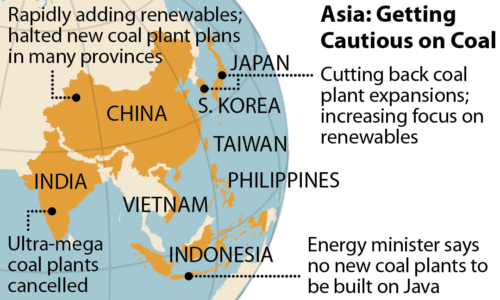

This line of inquiry resulted in a thoughtful silence from the analysts who had posited a business-as-usual scenario with rising demand from Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines as these emerging economies load up on new coal-fired power plants.

RECENT IEEFA REPORTS ON INDONESIA’S CAPACITY MARKET and the potential for stranded import-coal-fired power assets in the Philippines highlight the risk in this approach. So do developments all across Asia this year, in South Korea, for instance, in India, and in Taiwan.

RECENT IEEFA REPORTS ON INDONESIA’S CAPACITY MARKET and the potential for stranded import-coal-fired power assets in the Philippines highlight the risk in this approach. So do developments all across Asia this year, in South Korea, for instance, in India, and in Taiwan.

The analysts who took part in that recent discussion seemed not quite able to grasp the possibility of a world where the answer to Asia’s future demand for electricity might not depend on coal or on chronically over-optimistic forecasts for such demand. Instead, they hedged. One analyst even broke ranks to muse on the record-low pricing trends for new-solar auctions in India — before pivoting to concerns around how solar’s confirmed competitiveness in India might affect the willingness of banks to finance the many coal-fired power plants in the development pipeline there.

The analyst retreated from that line of thought, however, and ventured that downside risks to coal producers could be managed because coal demand growth among ASEAN members, particularly Indonesia and Vietnam, remains promising.

Analysts have yet to develop a structured way of thinking about how the advance of renewables will disrupt Asian coal markets.

It was a confident performance in chaos, revealing to careful listeners how analysts have yet to develop a structured way of thinking about how the advance of renewables will disrupt Asian coal markets, particularly for expensive imported thermal coal.

If investors in Asian energy markets lack a common language for discussing the impact of the Paris accords or of the changes technology is bringing to power-production markets, do they have any analytical tools to bring to bear on an increasingly unstable energy future?

The answer is yes, although it’s still difficult to know what to think about coal prices. What’s all but certain is that coal companies in Indonesia, the world’s biggest coal exporter, are likely to turn market enthusiasm about higher coal prices into a reason to raise more debt—and then squander the money on ill-advised investments in new coal-production capacity or mergers and acquisitions.

WHILE EXECUTIVES AT COAL FIRMS SAY THEY REMAIN BULLISH on demand- growth prospects across Asia, a wind-back in coal plant expansion plans in Japan and South Korea has seen forecasters put more reliance on the last bastion of import coal demand growth in smaller ASEAN economies.

The latest projections by the International Energy Agency have coal import demand continuing to rise over the medium term across Southeast Asia. But the agency also cautions that an increase in the capacity of new coal plants reaching financial close has slowed from a peak of 11 gigawatts (GW) in 2011 to 9.5GW in 2015 to a three-year low of just 7GW in 2016. Given that it takes four or five years to build a new coal plant after financial close, the IEA sees a momentum slowdown in new plant builds through 2020.

This cautious note is understandable, given that IEA is now acknowledging that renewable energy deflation has accelerated to 20 percent annually. IEEFA sees renewable pricing moving below grid parity this year in more markets. Saudi Arabia in October 2017 reported a 300-megawatt (MW) solar project tariff at a record low US$18 per megawatt-hour (MWh), down 25 percent on the record low set in the UAE in September 2016 of US$24, which itself was down 30 percent year over year. In India just this month, a record-low wind tariff was awarded on a 1,000MW tender, with pricing at US$38/MWh (down 25 percent year over year), surprising all analysts.

The question that lingers is whether investors are open to Asia’s rapidly changing energy fundamentals. Signs are that even the climate-change challenged are spotting growing risk on the balance sheets of Asian coal companies still drunk on growth.

Melissa Brown is an IEEFA energy finance consultant.

RELATED POSTS:

IEEFA Report: Philippine Banking Sector at Risk in Ill-Advised US$21 Billion Expansion of Coal Fleet

IEEFA Indonesia: A Potential Overcommitment to Coal-Fired Electricity Puts a Nation at Risk