As high LNG prices lure exporters into the market, Asian buyers may look for the exit

Key Findings

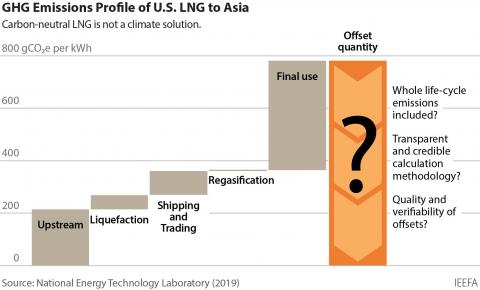

Price spikes and supply disruptions have dramatically strengthened the economic and security case against LNG. Some developing Asian nations may begin to reassess plans to boost LNG imports.

Sri Lanka is a prime example. Due to a near depletion of foreign currency reserves, Sri Lanka has had to borrow from the World Bank and India to purchase imported fuels.

As price volatility continues, mature and emerging LNG importers are seeking the nearest exit. If they take more permanent steps to limit LNG demand, exporters may find liquefaction assets increasingly unnecessary or unviable.

Volatility in liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets isn’t going away any time soon. On April 26, the World Bank warned of years of tightness and turbulence in global gas markets. As if to emphasize the point, Russia cut off gas supplies to two European Union nations the next day, sending yet another jolt into global gas prices and signaling Moscow’s willingness to wield gas exports as a weapon.

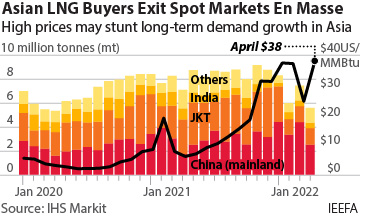

For the export industry, today’s high prices have been a defibrillator for LNG supply projects that had languished on life support for years. But for importers, particularly in Asia, high prices are beginning to crimp LNG demand. In the short term, sky-high prices have curbed their appetite for the fuel. Yet the more lasting problem for LNG exporters is erosion of demand creation in emerging markets.

Price spikes and supply disruptions have dramatically strengthened the economic and security case against LNG. Some developing Asian nations may begin to reassess plans to boost LNG imports. By the time newly sanctioned LNG export projects arrive in the market—unlikely for at least five years—prospective customers may already have moved on.

High prices are destroying Asian LNG demand, but for how long?

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, European nations vowed to ramp up LNG imports to wean themselves off piped imports from Russia. With global LNG suppliers already operating near full capacity and only modest new capacity additions slated for completion in the next several years, European buyers must pay hefty premiums to pull existing supply from other importers, primarily in Asia.

Prices, not government dictates, are directing traffic. To avoid high prices, Asian buyers have exited LNG spot markets en masse. Spot purchases have fallen to their lowest point since April 2020. Weather forecasts and storage levels will largely determine Asian buyers’ willingness to compete on price, at which point the arbitrage window for sending cargoes to Europe may begin to close.

Some buyers in China and South Korea have signed new long-term contracts to avoid spot markets. New 20-year purchase agreements may help push a limited number of export facilities over the finish line. However, a large majority of proposed projects, for example in the US, remain uncontracted. Despite new contracts, China’s LNG imports have fallen every month since December, while Beijing aims to ramp up pipeline imports from Russia.

Others buyers are also revealing potentially permanent shifts away from LNG. In Japan, a majority now supports a return to nuclear power for the first time since Fukushima, as fears that the country could struggle to maintain power supplies escalate due to high imported fuel costs. Although the country continues to invest in upstream LNG projects, the latest Strategic Energy Plan envisions a decline in the share of LNG in power generation from 37% to 20% by 2030.

If prices remain high and volatile, buyers may continue to avoid LNG spot markets while gradually backing away from LNG altogether.

The bigger picture: lack of long-term demand creation in Asia

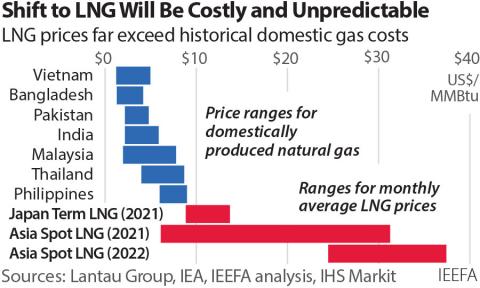

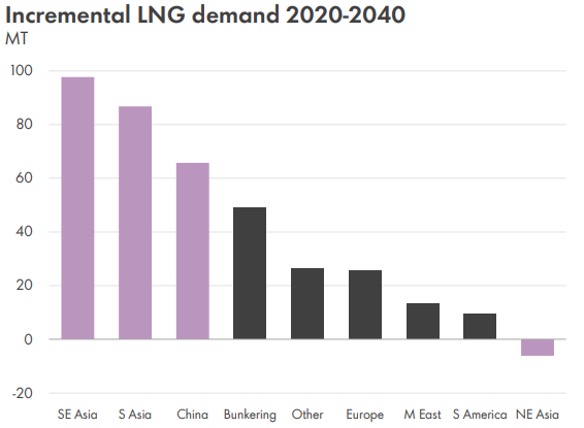

Southeast and South Asia are widely expected to drive global demand growth through 2040, but new LNG demand creation requires developing Asia to shoulder high, volatile fuel costs denominated in foreign currencies.

Sri Lanka is a prime example. US-based New Fortress Energy aims to stimulate LNG demand by establishing an import terminal and reiterated its commitment to the project in March, with targeted completion in 2023. This is despite the fact that Sri Lanka is on the brink of bankruptcy amid its worst economic crisis since independence. Due to a near depletion of foreign currency reserves, Sri Lanka has had to borrow from the World Bank and India to purchase imported fuels.

This is emblematic of a bigger regional issue: while companies and policymakers may push LNG imports, unaffordable fuel prices and macroeconomic instability may present hard limits to demand growth.

Pakistan has recently had to impose fuel and power cuts due to its inability to afford LNG and recurring defaults by contracted suppliers. Nearly 10% of the country’s power supply was stranded due to LNG shortages, resulting in nationwide load shedding. In March, Prime Minister Imran Khan’s ouster was due partly to the energy crisis, and the country is now at high risk of default. In addition to ongoing demand destruction, the country does not expect to build more LNG-fired power plants, and instead aims to bring the share of renewable energy to 60% of the national power mix.

Vietnam and the Philippines are expected to become new entrants to the LNG market this year, with new terminals expected online before the fourth quarter.

However, there are signs that national tolerance for LNG risks is waning. Fuel price volatility is undermining Vietnam’s ability to finalize long-term power sector plans. In the Philippines, the Department of Energy has promoted energy efficiency to lessen reliance on globally sourced fuels while promoting domestic renewable energy alternatives.

Conclusion

In the United States, no final investment decisions (FIDs) have been taken for new liquefaction projects since 2019. Now, LNG developers are pushing new projects to capture high global prices. While some may reach FID this year, industry expansion relies on high global prices and long-term purchase contracts. But these same conditions could potentially defeat the outlook for longer-term demand growth in Asia.

New projects are unlikely to come online before 2026. As price volatility continues, mature and emerging LNG importers are seeking the nearest exit. If they take more permanent steps to limit LNG demand, exporters may find liquefaction assets increasingly unnecessary or unviable.

The good times are rollin’ for LNG suppliers, but the question is: for how long?