Financing Just Transitions in emerging economies

Download Full Report

View Press Release

Key Findings

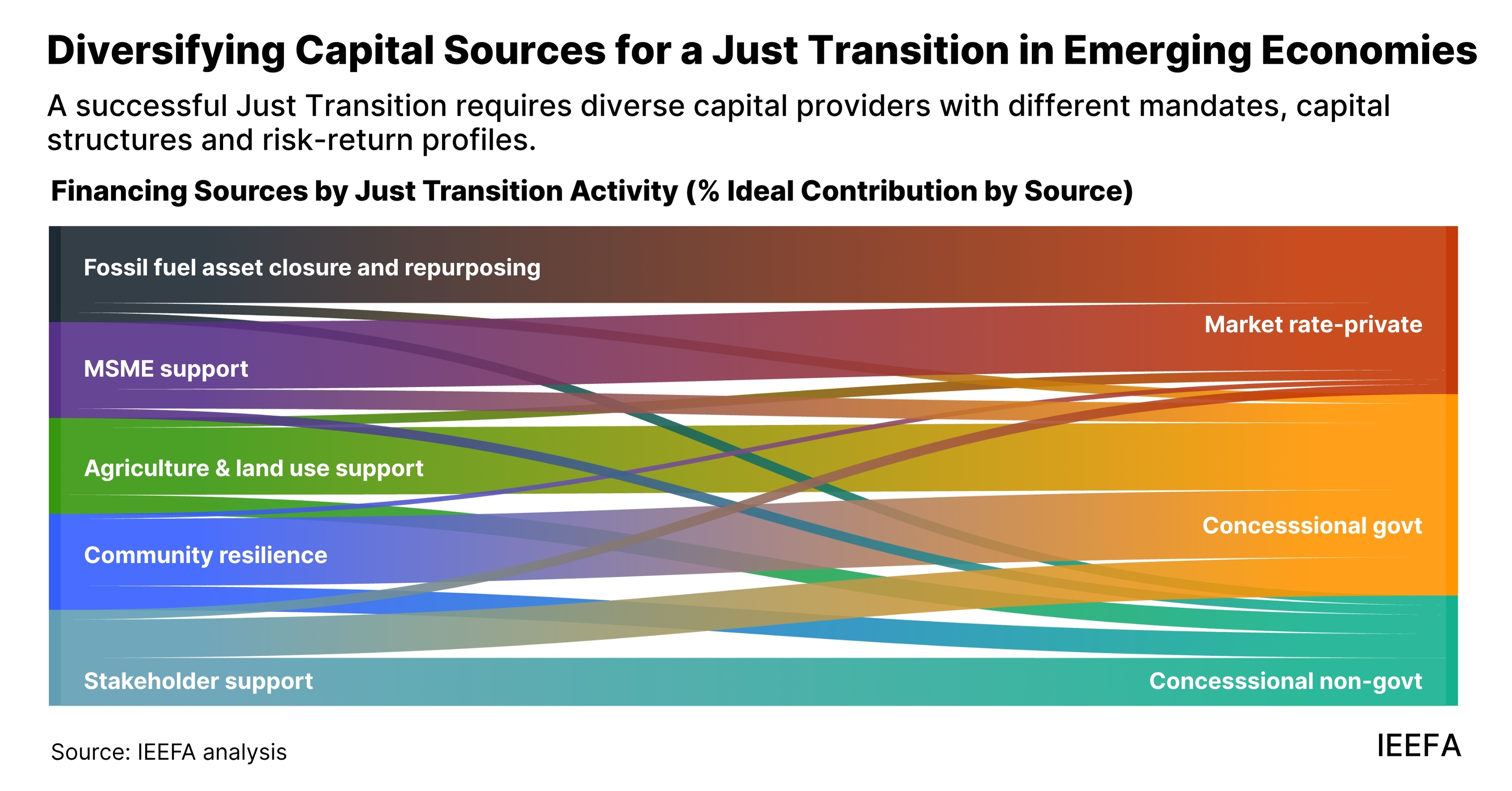

Supporting a Just Transition in emerging economies requires not only large-scale capital for infrastructure such as renewables, but also targeted financing for communities and small businesses. Capital should be matched to specific activities based on risk and impact.

Detailed and strategic investment plans help build investor confidence by clearly mapping projects, funding needs and socio-economic co-benefits.

Blended finance structures are crucial to fund non-commercial activities, such as worker reskilling, while attracting private investment for infrastructure.

Strengthening institutional co-ordination across ministries, empowering sub-national governments and embedding robust governance systems are critical to ensure transparency, accountability and long-term effectiveness of Just Transition financing ecosystems.

The global energy transition gives emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) a chance to combine climate action with inclusive economic growth. On one hand, the growth of low-carbon technologies can create new industries and jobs. On the other, it may disrupt regions and sectors that rely on fossil fuels. A Just Transition aims to manage this change fairly by protecting affected workers and communities, creating new opportunities for economic growth, and ensuring that the benefits of the transition are shared widely.

To achieve this, planning for energy transition must go hand in hand with planning for a Just Transition, especially in fossil fuel-dependent communities. This is to ensure that the shift to a low-carbon economy does not deepen existing socio-economic inequalities. In this context, Just Transition activities encompass a mix of hard energy transition assets, such as renewable energy, climate smart agriculture and climate-resilient infrastructure, and “softer” Just Transition aspects, such as responsible coal asset closures, stakeholder capacity building, labour reskilling, support for micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and community resilience. These activities lie on a spectrum of varying commercial viability. While grid-scale solar projects may attract private capital at market terms, non-commercial components like coal asset closure or social support measures often require concessional or grant-based finance. Given the interlinkages between these activities, they must be pursued through a co-ordinated “co-investment” approach that focuses on financing energy transition assets, such as renewable energy, alongside Just Transition initiatives like building community resilience in fossil fuel-dependent regions.

This report argues that financing a Just Transition in EMDEs will require significant capital deployment not only for infrastructure such as renewable energy, but also to support communities and small businesses through the transition. With fiscal pressures mounting and fossil fuel revenue expected to decline, EMDE governments should look beyond their own budgets to a diverse set of capital providers, including multilateral development agencies, private investors, development banks and philanthropies. The financing challenge is not only about scale, but also about mapping suitable forms of capital to the right activities based on their risk-return profiles and developmental impact.

To illustrate how this can be achieved, this report draws on practical examples from several case studies, identifying mechanisms to structure similar financing interventions in EMDEs. The Philippines’ Accelerating Coal Transition (ACT) investment plan shows how concessional debt and grants coupled with private capital can enable early coal retirement and repurposing with social support. South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP) underscores the importance of institutional co-ordination, stakeholder engagement and dedicated funding platforms. In India, targeted medium, small and micro enterprises (MSMEs) and agriculture programmes backed by multilateral and philanthropic co-financing are helping vulnerable sectors decarbonise while building economic resilience. In Ethiopia, the United Nations Green Climate Fund (GCF) financed a rural water programme that illustrates the value of grant-based financing in fragile contexts.