Financing the JETP: Making sense of the packages

Key Findings

Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) financing proposals from the International Partners Group (IPG) governments could be catalytic in transforming Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa’s energy economies. However, much of the money takes the form of business-as-usual development finance, making it unlikely that JETP monies will make a dent in each country’s ambitious US$100 billion-plus transition plans.

IPG governments need to better organize and consolidate their proposals to create an efficient environment for reaching financing agreements. JETP beneficiary governments would be well served to take practical, realistic views of the investment priorities to better meet the IPG in the middle and ensure productive energy transition investments are achieved.

JETP needs to be a true partnership between financiers and beneficiaries, with the mutual goal of large-scale, near-term, outcome-oriented plans for decarbonization. JETP negotiations would benefit from having fewer, better-coordinated financing packages, comprised of larger amounts of money that can be flexibly deployed in support of each country’s JETP investment plans.

Cumbersome proposals now need to harmonize catalytic money with investment plans

Just Energy Transition Partnerships, or JETPs, are ambitious country-level plans designed to support select developing economies’ transition from carbon-intensive energy systems to sustainable development pathways. JETPs were created to help provide the financing to retire high carbon-emitting power plants, aid in developing renewable energy generation and storage systems, and enhance the efficiency of the transmission grid while providing equitable treatment of labor that might be displaced by these transitions. Accordingly, JETPs are massive in scope, meant to radically transform how energy systems operate. Donors and investors have pledged more than US$46 billion to implement them.

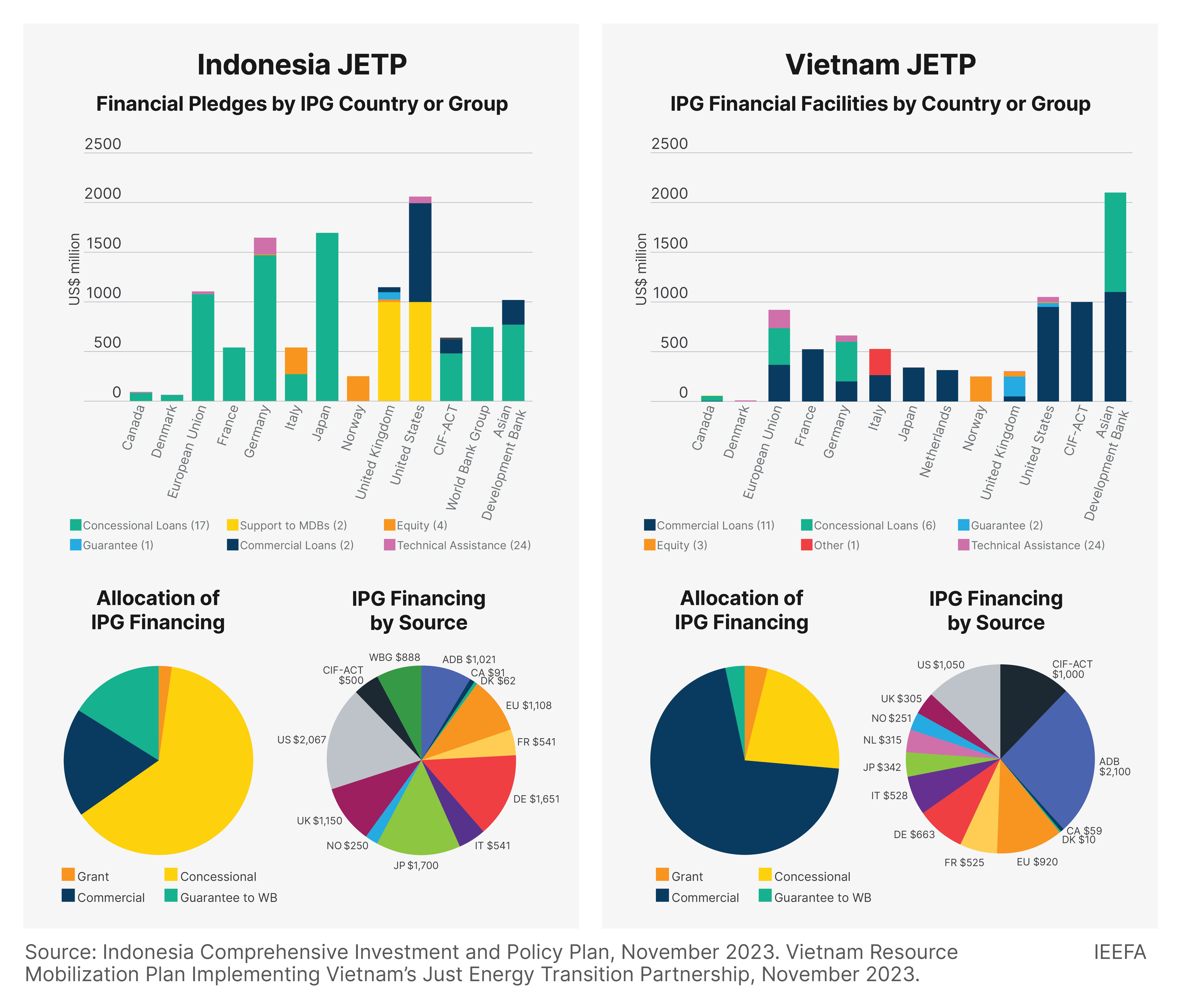

There are currently four JETP countries: South Africa, Senegal, Indonesia, and Vietnam, with the latter two being the largest proposals, covering US$20 billion and US$15 billion of proposed financial support respectively. Approximately 50% of those amounts will come from public and multilateral entities; the other half will be provided by private sector investors. An amalgam of grants, concessional loans, guarantees, and commercial loan facilities will help finance the initial round of JETP investments over a five-year period. The idea is to mix the no-cost grants and low-cost concessional funds with commercially priced private sector capital to lower the overall cost, achieving “blended financing.”

Public funding is being offered from a club of industrialized countries providing bilateral development monies under the moniker of the International Partners Group, or IPG. The group includes Canada, Denmark, the European Union, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Norway, United Kingdom and United States. JETP is also supported by multilateral development banks (MDBs), philanthropies, and the multi-donor funded and MDB-operated Climate Investment Funds (CIF). Private sector funding is being coordinated through the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), with a JETP working group of seven global investment banks representing 675 private sector financiers.

JETP has been hailed as a game-changer for decarbonization in its scale and impact, allowing countries to tackle the full scope of energy economy transition issues simultaneously — issues that each country and development agencies have jointly worked on piecemeal for years. But attempts to leapfrog decades of entrenched interests, legacy infrastructure and fossil mindsets have proven to be challenging because the JETP effectively requires overhauls to national energy policy and holistic examinations of national economic development plans and the finances behind them. The JETPs have languished, bogged down in the detail of the IPG’s funding sources, allocations to end uses, and investment priorities. The delays have spurred some critics to describe the JETP concept as a failure, but the jury is still out; globally, no programs of such size have been proposed.

Why have there been such difficulties in approving programs that appear to have such shared interests? The troubles can be broken down into scope, parties involved and mechanics of delivery.

At the JETP launch, joint statements between the IPG and each beneficiary country called for the formation of national committees, plan issuance, and agreement on first deals, all within months from their announcements. These timelines have proven to be highly aggressive, with IPG member expectations appearing more focused on fitting achievements to an annual political calendar ahead of the next G-20 meeting or COP summit, rather than on outcome suitability for JETP beneficiaries.

Initially, IPG funds came with broad goals but lacked definitions and focus, fueling speculation within the JETP countries that they could be used for almost anything — not what the IPG intended. This led to negotiation stalemates. South Africa, the first JETP country to reach this impasse, stepped away from the negotiating table to craft a comprehensive national strategy called the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan, or JET-IP, completed in November 2022. Their JET-IP identified the country’s policy and investment priorities for the next 20 years, allowing for more focused IPG negotiations, and prioritizing efforts to be financed under JETP.

Indonesia released its Comprehensive Investment and Policy Plan (CIPP) in November 2023, and Vietnam issued its Resource Mobilization Plan (RMP) at the beginning of December 2023. The scope and magnitude of the country-based plans for Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa make it clear that the IPG’s JETP funds are merely a down payment on hundreds of billions of dollars of needed transition and decarbonization investments over the coming decades. The plans define the scope of the transition and break down decarbonization goals that can be matched with investment projects. With these priorities identified, negotiations between JETP countries and the IPG can now be more focused.

IPG funding packages are not neatly wrapped

To observers, the need to develop such investment plans seemed puzzling since announcements made IPG funding sound like a consolidated package of support to which countries simply needed to agree. But the political and economic realities of the IPG’s JETP funding are far from streamlined and the process of negotiating access has been chaotic.

Indonesia, for example, will receive $20 billion of support from 10 IPG countries, two MDBs — World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB) — and CIF, divided into more than 50 funding packages, ranging from $700,000 to $1.7 billion. Vietnam’s $15 billion is similarly disjointed, with 11 IPG countries, ADB and CIF spreading their money over more than 40 financing facilities. In both countries’ cases, significant percentages of IPG funds are tied to projects with pre-conditions and/or identified pet projects tied to their access. Almost 20% of Vietnam’s JETP funds are earmarked for specific projects; in Indonesia, 55% have strings attached.

Most of this earmarked spending was identified long before each country came up with its current JETP investment plans. In some cases, projects were under discussion with donor countries before JETP even existed. As such, IPG countries are not really proposing new, additional funding. Regardless of the proposal vintage, each project or source of funding has special qualification processes and operational requirements that the beneficiary country must meet.

These pre-determined end uses particularly hurt Indonesia’s CIPP ambitions, which identifies 400 projects across generation, transmission, storage and other critical investments needed to affect the transition over the remainder of this decade. Only a few of these projects were part of IPG negotiations, meaning that most need to be newly considered. With more than half of the IPG funds already obligated, that leaves a majority of the CIPP projects without funding. Indonesian officials may need to return to IPG parties to pitch their list, potentially undoing previous agreements to make room for clearly identified priorities.

Some proposed IPG financing facilities are not directly provided to a JETP beneficiary country at all. In both the Vietnam and Indonesia proposals, the UK has pledged a $200 million mix of debt, equity and guarantees from a multi-donor entity called the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG). The money is meant to fund new, privately developed infrastructure projects originated via PIDG’s appointed development company, InfraCo Asia, which may or may not succeed in finding, preparing and closing projects in each country.

In the case of IPG funding in Indonesia, the UK and U.S. have offered as much as $2 billion of guarantees to the World Bank that would extend the bank’s prudential credit limit to the country, an amount accounting for 20% of the IPG’s public support component under the Indonesia JETP. The guarantees will provide extra financial capacity beyond the bank’s traditional allocation limit for Indonesia country programs, an important detail since MDB partnerships with JETP countries cover a wide range of social and economic areas with equally high priorities like health, education, or agriculture.

However, it is not clear how the World Bank would leverage the UK and U.S. guarantee funds to entice larger amounts of private sector investment, if at all. To date, World Bank has favored traditional loans made directly to the sovereign, whether through bank-controlled projects or policy-based lending and has been resistant to offering partial risk guarantee products that could be used to cover private sector investments. (The World Bank’s systematic missed opportunity in using guarantee capacity was addressed by an IEEFA commentary earlier this year.)

Guarantees, however, could target specific political, policy or public sector creditworthiness risks that could help overcome reluctance amongst private sector lenders or equity investors. Used wisely, World Bank guarantees could leverage multiples of their face value, transforming the $2 billion in guarantees into $8 billion or more in project-level investment, helping achieve a cornerstone JETP concept of lower cost “blended financing.”

Despite this call for leverage, examination of Indonesia’s CIPP shows that more than 55% of public sector IPG money appears predestined for either “plain vanilla” sovereign projects such as loans to state-owned entities, or for policy support loans that are generally bulk allocations to the state budget that ostensibly cover the implementation costs of proposed reforms. This is effectively business-as-usual multilateral and bilateral development aid. Given these planned allocations, it is not obvious how concessional IPG funds will be available for Indonesia’s project-level investments.

Vietnam’s JETP finance plan sits in an even more challenging position. More than US$10 billion, or about 70% of IPG funds slated for Vietnam, are identified as commercially termed loans. Concessional loans account for less than a quarter of IPG’s proposal, with more than 80% of low-cost funds committed to already-identified sovereign projects. There is no clear pathway to using IPG funding to create a blending of any meaningful scale and advance the more than 200 projects in the RMP.

Moving ahead

There is a perception that IPG and JETP country governments hold joint roundtable meetings to agree on a neat package. The reality is far more chaotic. Each of the IPG members has its own political and environmental agendas. The combination of proposals and interests has forced JETP beneficiary government officials to spend countless hours attempting to nail down the details of funding.

However, much has been learned from the disjointed start to the JETPs. The IPG should do everything possible to become a cohesive group, simplifying the funding process. Beneficiary governments would be well served by critically reviewing and refining project pipelines for realism and priorities. Better projects, with strong climate rationale and good preparation, are key to reducing risk, advancing implementation timeframes and obtaining investment capital. There should be a strong focus on leverage to assure funds available are stretched to their maximum potential.

JETP is not a giveaway, and the projects financed under the package and the policies behind them must be sound and constructively contribute to a sustainable pathway. They cannot be decoys for investing in one green area while polluting in another. Indonesia, for example, has not included captive coal-fired power plants that support smelting in the scope of its JETP.

Vietnam’s RMP is heavy on unproven technologies like ammonia co-firing, carbon capture and storage, and hydrogen that appear to be catering to keeping coal plants operating rather than truly phasing them out.

JETP needs to be a true partnership, with the mutual goal of large-scale, near-term, outcome-oriented plans for decarbonization. Guiding principles for engagement success could feature:

- Beneficiary leads, group decides. Priorities should be set by the country benefitting from the funding, with advice and guidance from IPG countries and multilateral organizations.

- Frictionless negotiations. IPG should offer a central point of coordination or, for areas where multiple IPG donor countries are interested in a specific theme, thematic leaders to represent those donors and create conditions for focused negotiations with the beneficiary.

- Streamlined monies. IPG monies should be offered via the fewest number of financing facilities, each in the largest possible amounts, with the broadest uses.

- Fund flexibility. More of the IPG funds should be “open” or “unprogrammed” so beneficiary governments can better match funding to priority JETP projects.

The amounts of money the IPG has put on the table are consequential. They have caught and held the attention of the beneficiary governments, driving them to devise comprehensive transition plans in their national context. Now, it is up to all of the governments involved to buckle down and focus on implementation. The IPG needs to become better organized and coordinated, facilitating getting to “yes.” The JETP beneficiary governments need to be rooted in practical reality regarding their policies, investments and timing. Some investments and some matter of progress will come out of the JETP process. The question is will JETP be chaotic, piecemeal and incremental, or will it become the holistically transformative vehicle it was intended to be?