The feasibility of rapid transitions: 80 percent carbon-free electric grid is reachable

Key Findings

The Biden administration’s clean energy plan—80 percent carbon-free electricity by 2035—can seem like a daunting target. But there are templates for that transition, in Texas and the formerly coal-dominated Southeast.

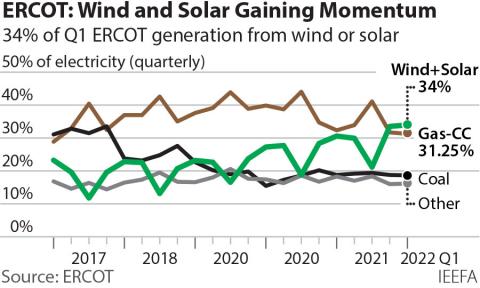

In 2022, solar and wind generated a record 30.5% of the electricity in ERCOT, the system operator that handles roughly 90% of Texas’s electric demand. This is a four-fold increase since 2010, when wind accounted for 7.8% of the ERCOT market.

The growth in wind and solar market share is noteworthy for several reasons: It has occurred even as overall ERCOT demand grew significantly during the same period; there was no solar in the market in 2010; and the increases occurred without significant federal backing.

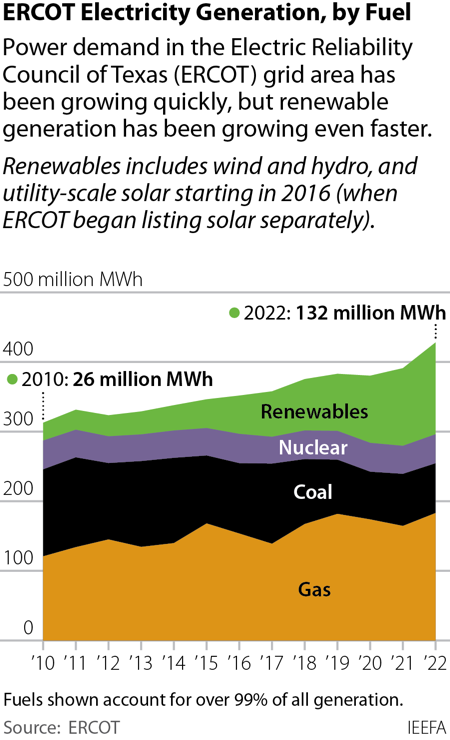

Texas is by far the largest electricity generator in the U.S., and has been for years. In 2010, the state generated 409.4 million megawatt-hours (MWh) of electricity. In 2021, the total was 483.5 million MWh, up 18%. The second-largest state electricity generator in 2010 was Pennsylvania, which produced 178.9 million MWh; in 2021, it was Florida, at 239.1 million MWh. So, not only is Texas still the largest generator, but the gap between it and the second-largest state has widened. Within the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), generation grew even faster, climbing from 316 million MWh in 2010 to 430.1 million MWh in 2022, an increase of 36.1%. (We use the full-year 2022 data released by ERCOT throughout this analysis; final year-end data for other states is not yet available from the Energy Information Administration.)

Wind and solar have outgrown the market, and have done so by a significant degree (there is only a negligible amount of hydro in ERCOT). In 2010, wind generated 24.7 million MWh, 7.8% of total demand. By the end of 2022, wind generation had climbed to 107.2 million MWh, a whopping 434% increase—and had grown to 24.9% of the electricity generated. During the same period, solar generation rose from essentially zero—it wasn’t even separately tracked by ERCOT until 2016—to 24.1 million MWh in 2022, or 5.6% of all energy generated.

Wind and solar have outgrown the market, and have done so by a significant degree (there is only a negligible amount of hydro in ERCOT). In 2010, wind generated 24.7 million MWh, 7.8% of total demand. By the end of 2022, wind generation had climbed to 107.2 million MWh, a whopping 434% increase—and had grown to 24.9% of the electricity generated. During the same period, solar generation rose from essentially zero—it wasn’t even separately tracked by ERCOT until 2016—to 24.1 million MWh in 2022, or 5.6% of all energy generated.

Together, the two resources accounted for 30.5% of ERCOT demand. Coupled with the system’s two nuclear plants (the South Texas Project and Comanche Peak), ERCOT’s carbon-free electricity topped 40% for the first time. Meanwhile, 2022 was the first year coal and gas generation dropped below 60%; in 2010 it was 77.7%.

Another way of looking at the rapid renewable growth in ERCOT is comparing its generation to the rest of the U.S.: If considered as a state, ERCOT’s wind and solar generation of 111.1 million MWh in 2021 would have made it the 12th largest, generating almost as much as all the power produced in Michigan. Given the sharp increase in generation in 2022 to 131.3 million MWh, ERCOT wind and solar will almost certainly jump into the top 10 state generators when EIA’s final figures are available.

And the outlook for continued movement away from fossil fuels and toward renewables remains positive, despite efforts in Texas to revise ERCOT’s structure to favor gas generation. Installed wind and solar capacity in ERCOT now totals 53,169 megawatts (MW). Wind accounts for 36,143MW and solar for another 14,557MW. Significant additional growth is coming. ERCOT’s latest capacity report projects that an additional 20,133MW (13,221MW of solar, 4,150MW of battery storage, and 2,762MW of wind power) will enter commercial service in 2023. Further out, the system’s latest generator interconnection report shows an additional 26,000MW of wind, solar and storage is currently in the development process, with signed agreements for grid access.

Quick transitions are indeed possible.

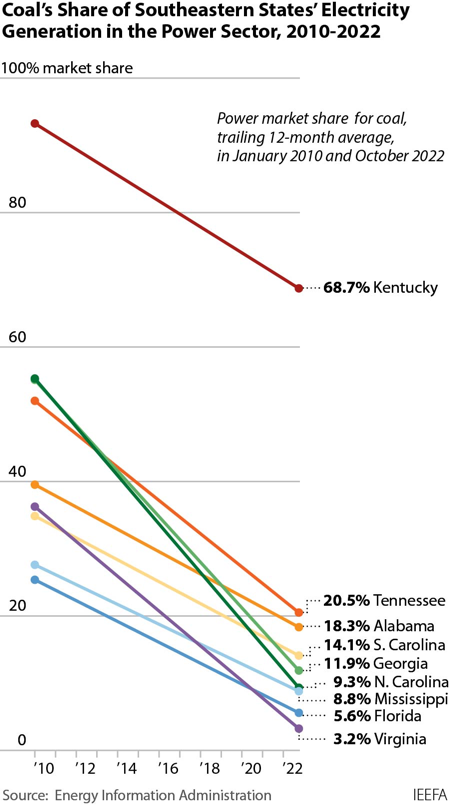

ERCOT is not the only example of rapid change in the U.S. electricity sector. The southeastern U.S. has been the site of an equally dramatic change in the past decade, as the region’s electricity generation has shifted decisively away from coal. In 2010, every one of the nine states in the region (Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Tennessee and Kentucky) generated more than 20% of their electricity from coal, including three that generated more than 50%, and Kentucky, which reported more than 90%. By October 2022 (the most recent data available from EIA), only two states were still getting more than 20% of their power from coal, and four were getting less than 10%. Even in coal-dominated Kentucky, the change has been stark, with coal’s share falling to an average of 68.7% for the 12 months ending October 2022.

Elsewhere in the region the changes were even more dramatic. In Georgia, for example, coal generation dropped from 72.6 million MWh in 2010 to 14.5 million MWh in the 12 months ending in October 2022, an 80% decline. As a percentage of in-state electric generation, coal fell from 54.7% in 2010 to just 11.9% through the 12 months ending in October.

Virginia is also telling, especially as in-state electricity generation climbed 25% during the period, while the region reported almost no generation growth. In 2010, coal-fired power totaled 24.7 million MWh and accounted for 34.9% of total electric generation. For the 12 months ending in October 2022, coal generation had almost disappeared, falling to 3.1 million MWh, or 3.2% of total generation.

The Southeast transition from coal was driven by a rapid shift to gas generation. In Virginia, for example, Dominion Energy brought four combined cycle gas turbine units online in the 2010s with a total capacity of 5,302MW. All four have posted average capacity factors of far more than 60% since beginning operation, enabling the utility to shift from coal while still meeting rising demand. Similar buildouts occurred in other states in the region.

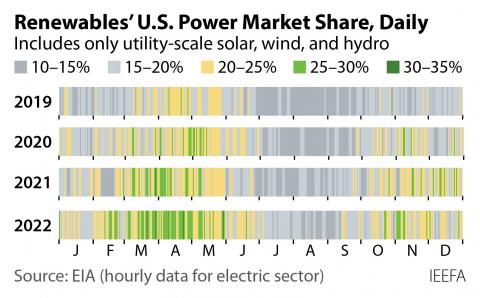

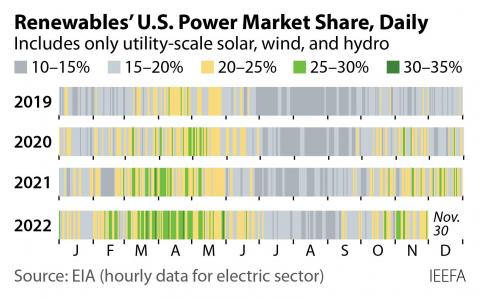

As in Texas, this shift away from coal shows just how rapidly transitions can occur, and the beginnings of such a transition are becoming apparent at the national level. In its January 2023 Short Term Energy Outlook, EIA projects that renewables’ share of the U.S. electric sector will climb to 26% in 2024, cutting into the market share of both gas- and coal-fired generation. Driven by the recent passage of the Inflation Reduction Act and the decade-long cost declines and performance improvements for wind, solar and battery storage, it is increasingly clear that a rapid transition away from fossil fuels and to renewables is possible, putting the 2035 carbon-free electricity goal well within reach.

Dennis Wamsted ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy analyst.

Seth Feaster ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy data analyst.