BHP: As the steel technology transition accelerates, met coal’s biggest exporter wants to get even bigger

Key Findings

BHP’s takeover bid for Anglo American, if successful, would see the world’s largest metallurgical coal exporter become even bigger, amid a worsening outlook for met coal and growing investor pressure over Scope 3 emissions.

While the bid is largely driven by Anglo’s copper assets, BHP’s interest in hard coking coal reflects its continued belief that carbon capture, utilisation (CCUS) and storage offers a viable option for decarbonising steelmaking.

The long-term outlook for metallurgical coal is declining as the steel technology transition away from blast furnaces towards alternatives like direct reduced iron (DRI) accelerates.

The takeover could put an end to Anglo’s more ambitious Scope 3 emissions reduction targets, and would see investor pressure grow for BHP to act on Scope 3.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

BHP’s US$40 billion takeover bid for Anglo American is mainly about copper. However, a successful takeover would also make BHP an even larger metallurgical coal miner as the long-term outlook for the steelmaking commodity worsens and investor pressure on Scope 3 emissions rises.

In a statement to the ASX, BHP noted “The combined entity would have a leading portfolio of large, low-cost, long-life Tier 1 assets focused on iron ore and metallurgical coal and future facing commodities, including potash and copper.”

A successful bid would add Australia’s second largest metallurgical coal exporter to the biggest. BHP has been highly critical of updated Queensland coal royalty rates but now appears to favour the addition of Anglo’s coal mines in the state.

It’s possible that BHP may seek to spin off the enlarged coal business at some point in the future. Nonetheless, as it stands, the takeover proposal involves the demerger of Anglo’s South African iron ore (Kumba Iron Ore Ltd) and platinum-group metals (Amplats) businesses. Other Anglo businesses – including De Beers – would be up for strategic review post-completion.

BHP has recently been offloading its lower-quality metallurgical coal mines to the likes of Whitehaven Coal in the belief that steelmakers will gravitate towards higher quality as they seek to reduce blast furnace emissions. Anglo’s Queensland coal mines produce the hard coking coal that BHP is keen on.

BHP’s hope that hard coking coal will be in demand for decades is at least in part based on its continued belief that carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) will play a meaningful role in decarbonising blast furnace-based steelmaking and maintain demand for metallurgical coal. This is despite an abundance of evidence to the contrary.

IEEFA’s new report on CCUS for the steel industry finds that the poor performance of carbon capture technology makes it increasingly unlikely to play a major emissions reduction role, as steelmakers increasingly turn to better technology alternatives like direct reduced iron (DRI).

There are no commercial-scale CCUS plants for coal-based steelmaking anywhere in the world, with almost nothing in the pipeline.

The German think tank Agora Industry highlights that virtually all steel companies that plan to build low-carbon steelmaking capacity at commercial scale have opted for hydrogen-based or hydrogen-ready DRI plants, not CCUS. The 2030 project pipeline of DRI plants has grown to 94 million tonnes a year (Mtpa), while the pipeline for commercial-scale CCUS on blast furnace-based operations amounts to just 1Mtpa.

As well as disappointingly low capture rates, CCUS for integrated, blast furnace-based steel plants does nothing to address the methane emissions associated with metallurgical coal mining. Total methane emissions from coking coal mines globally totalled 10.5 million tonnes (Mt) in 2023, according to the International Energy Agency. This equates to up to 913.5Mt of CO2 equivalent over a 20-year impact timeframe. For comparison, global emissions from steelmaking amount to around 2,800Mt of CO2 per annum.

Global steelmakers’ shift from coal-consuming blast furnaces to recycling steel in electric arc furnaces (EAF) and DRI-based processes is already well underway. Using green hydrogen in DRI and renewable energy to power EAFs will enable the production of truly low-carbon steel – a feat that CCUS looks unable to replicate, with implications for long-term metallurgical coal demand.

Declining long-term outlook for metallurgical coal

The accelerating steel technology transition away from blast furnaces means the long-term outlook for metallurgical coal is changing.

The Australian government’s March 2024 Resources and Energy Quarterly (REQ) report highlights that world trade for metallurgical coal is declining. From 349Mt traded in 2023, trade will drop to 333Mt by 2029, according to the forecast. Australia is the world’s largest metallurgical coal exporter by far, but Australian exports are forecast to peak in two years’ time and then decline out to the end of the decade.

This does not sound much like a commodity with a long and bright outlook unaffected by technology change. Anglo American might be inclined to agree – in contrast to BHP’s idea that metallurgical coal demand will last for decades, Anglo stated last year that the steel technology shift away from coal was a matter of only 10-15 years.

Scope 3 emissions implications

Anglo’s long-term view of metallurgical coal likely influenced its Scope 3 emissions approach. The company is aiming to cut Scope 3 emissions 50% by 2040.

In contrast, BHP does not have a measurable Scope 3 emissions target. It does have a “goal” to reach net zero Scope 3 emissions by 2050 but, as BHP explains, a goal is not the same as a target.

One outcome of this potential takeover could be the end of one of the more ambitious Scope 3 reduction targets among major miners.

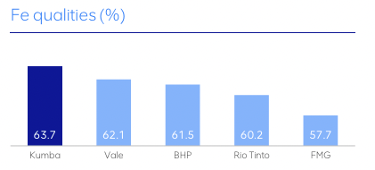

The higher quality of Anglo’s iron ore is a further driver of its Scope 3 ambition. It produces ore with high iron content suitable for lower-carbon, DRI-based steelmaking (DR-grade) at its Minas-Rio mine in Brazil, with the potential for significant expansion. The output of its Kumba Iron Ore operations has a higher iron content than most Pilbara production (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Kumba iron ore quality vs production from the big four iron ore miners

Source: Anglo American-Kumba Iron Ore

While Kumba Iron Ore would be demerged as part of the proposed takeover – presumably because BHP wants to limit its exposure to South Africa and its struggling rail logistics – the Minas Rio mine would add some DR-grade ore to BHP’s blast furnace-grade Pilbara operations.

BHP has joined Rio Tinto and BlueScope Steel in seeking ways to make Pilbara ore suitable for DRI-based steelmaking, but it has so far shown no interest in developing high iron content, DR-grade mines, in contrast to the other major iron ore miners.

In its recently released Integrated Report, Kumba noted a “significant opportunity to reduce our Scope 3 emissions” and highlighted that “there are growing calls on companies to manage Scope 3 emissions…”.

The huge investor rejection of Woodside’s climate plan further underlines the point. An even larger coal business and continued support for mired and underperforming CCUS technology will bring further pressure for BHP to act on its Scope 3 emissions.