Beyond COP28: Financial institutions should adopt nuanced transition finance frameworks to support net zero

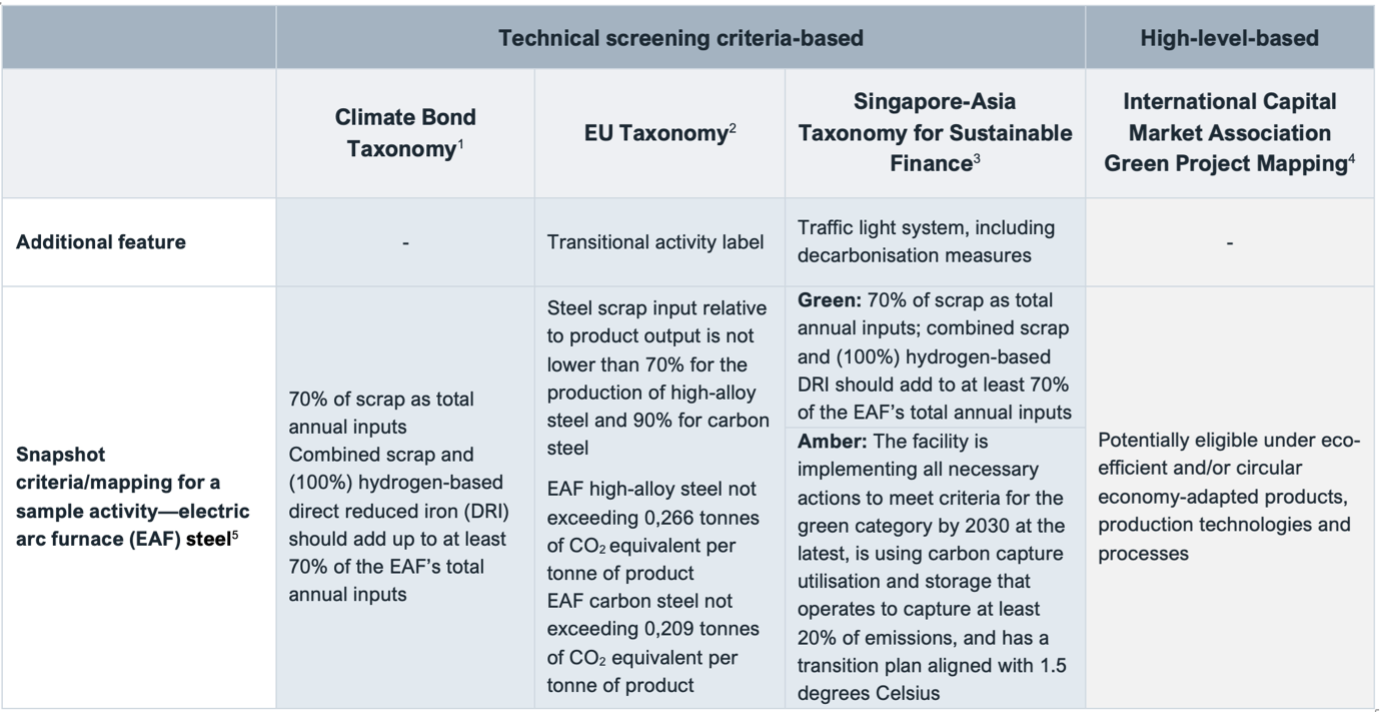

Key Findings

The development of a common transition finance framework remains largely absent after COP28.

While GFANZ provides a high-level framework, financial institutions should rely on science-based tools to seek transition finance opportunities.

A financial institution’s transition finance framework should ensure that the flow of use of proceeds to non-qualified activities, especially the expansion of fossil fuels, is not allowed.

Transition finance should focus on country- and sector-specific feasibility assessments for activities and considerations of credible transition plans for entities, developed with a well-defined timeframe.

The 2023 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) prompted some positive developments on climate finance. Meanwhile, “transition finance”—having lagged behind—is becoming an important theme this year.

The real economy increasingly seeks capital under a “transition” label, notably for decarbonising high-emitting, “hard-to-abate” assets where zero- or near-zero-carbon alternatives are not available; financial markets offer more transition-labelled products and tools.

Studies often point to the large climate investments required between now and 2050 to stay within a 1.5-degree pathway. But an estimated aggregate amount of transition finance needed is less discussed (although some sector-specific estimates are available), perhaps because a standard definition of the term is absent. The description of high-emitting, “hard-to-abate” assets most in need of transition finance is also unclear.

Increasing rigour in transition finance?

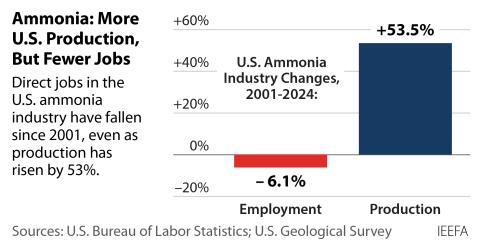

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), a coalition of net-zero-committed financial institutions (FIs) formed in 2021, launched a consultation in September 2023 on a sector-agnostic proposal to further define transition finance. The GFANZ secretariat subsequently released a technical review note at COP28. The GFANZ definition of transition finance is built upon four financing strategies the coalition first recommended in 2022: climate solutions, aligned, aligning and managed phaseout. The note also outlines methodologies to calculate decarbonisation contribution.

In addition, the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group introduced 22 principles for transition finance. A high-level framework is a good start, but may not account for country-specific differences in the energy mix, industrial emissions breakdown, economic and technological reality, and political and institutional capacity. IEEFA calls for more nuanced assessment methods when considering transition finance opportunities.

Figure 1: GFANZ’s four strategies provide a high-level view, but FIs will need more nuanced considerations when screening opportunities

Source: IEEFA.

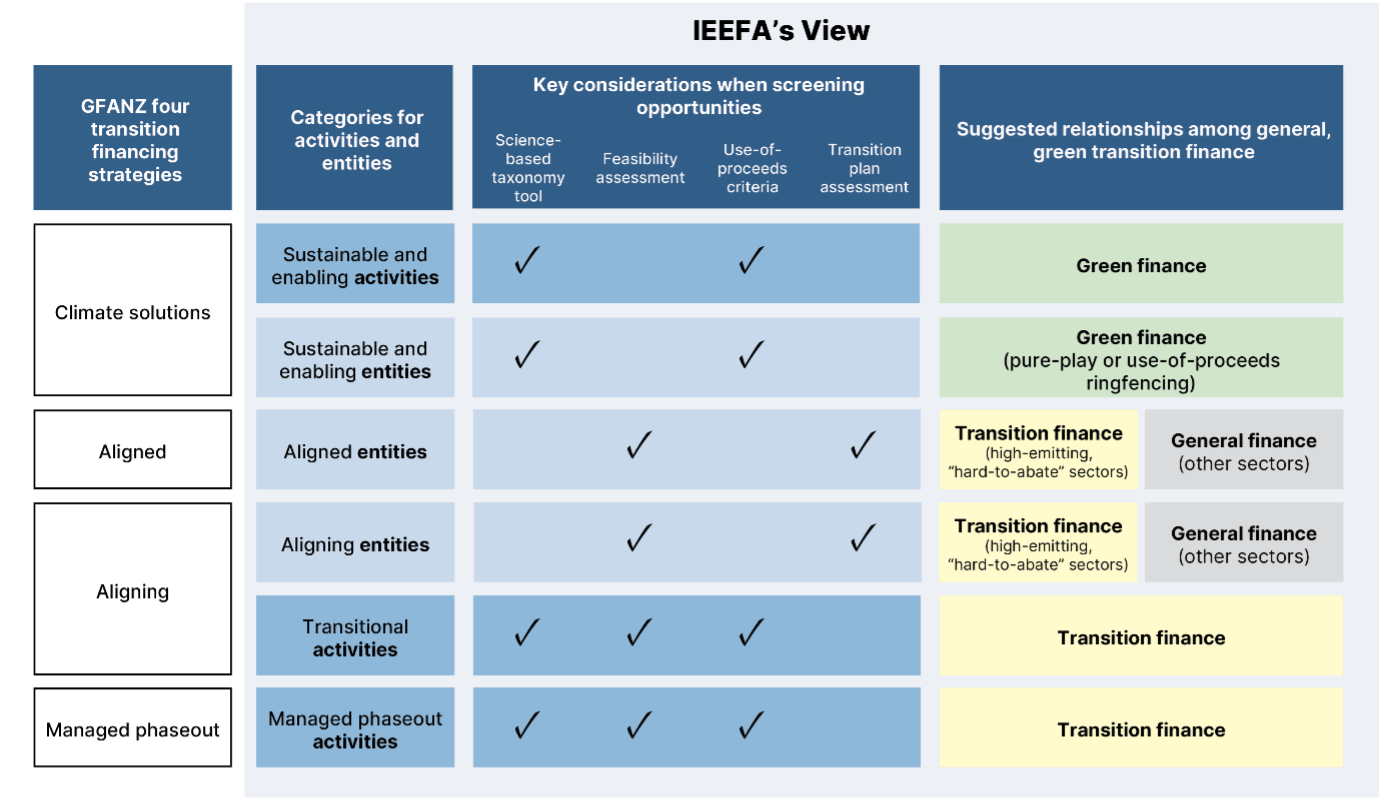

Distinguishing green and transition finance

The European Commission has attempted to differentiate transition finance from green finance and suggested that in the long term, all transition finance will be considered either green or low impact. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has highlighted that transition finance focuses on the dynamic and forward-looking process of becoming sustainable. This is a plausible approach catering to technological advancements over time. A clear distinction between green, transition and general finance can lower greenwashing risks.

Source: IEEFA, adapted from the Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/1425 of 27 June 2023 on facilitating finance for the transition to a sustainable economy.

GFANZ seems to suggest that transition finance be an umbrella term for all strategies contributing to transition. It describes climate solutions, one of the four categories, as sustainable or enabling solutions often qualified under green finance. The GFANZ secretariat has subsequently clarified that transitional activities are included in the aligning category.

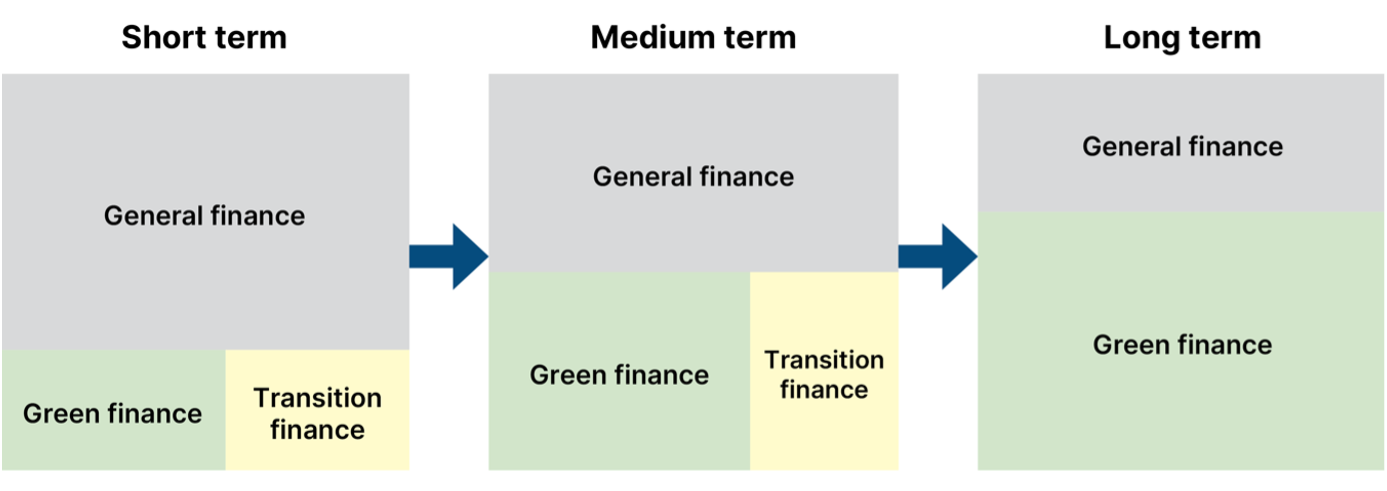

Using science-based thresholds to define transitional activities

The GFANZ framework’s principle-based nature provides a holistic view to begin with. FIs will need to turn to taxonomy tools, which may not all be well designed or fit for purpose, thereby necessitating caution when applying. For example, IEEFA has pointed out that the latest planned revision to the Indonesian taxonomy may be “muddying the waters regarding transition needs.”

To foster a solution’s science-based substantial contributions to transition, FIs should, where possible, opt for technical screening criteria-based taxonomies. For example, while the EU taxonomy attracts controversies, it provides safeguards through the “do no significant harm” criteria. The recently launched Singapore-Asia taxonomy builds upon science-based criteria and distinguishes between green and transitional (or “amber”) activities. Japan’s planned “transition”-labelled bond issuance this month has a sizable offering totaling JPY 1.6 trillion (US$11 billion). The intended use of proceeds to research and development projects and subsidy programmes are verified by the Japan Credit Rating Agency to be 95% aligned with the new draft Climate Bonds Standard, which allows some flexibility for early-stage research spending.

Figure 3: Science-based criteria provide FIs with concrete screening tools for activities

Snapshot comparison of key taxonomies/mapping

1 Climate Bonds Initiative. Climate Bonds Taxonomy.

2 European Commission. EU Taxonomy Navigator.

3 Monetary Authority of Singapore. Singapore-Asia Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance. December 2023.

4 International Capital Market Association. Green Project Mapping. June 2021.

5 IEEFA. Competing for Green Steel: National advantages and location challenges. January 2024.

Assessing and comparing early-stage technologies in a continuous manner

The OECD has highlighted that transition finance bears a high risk of carbon lock-in (where fossil fuel assets continue to be used) and emphasised the role of feasibility (economical, institutional and social) in eligibility assessments. GFANZ has referenced this consideration when assessing early-stage technologies in the aligning category. The extent to which the proposed decarbonisation contribution methods can determine an absence of low- or zero-carbon alternatives remains opaque.

For example, IEEFA has noted that major carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects rarely meet their targets for CO2 capture and storage, and the majority are used to produce more fossil fuels: Our 2022 study reviewed the capacity and performance of 13 flagship projects and found that 10 failed or underperformed against their designed capacities, mostly by large margins. In some sectors, non-CCS alternatives exist and are preferable. For example, IEEFA research has found that the Middle East and North Africa region is well equipped to produce cheap green hydrogen domestically for iron and steel production thanks to its excellent solar resources.

An FI should conduct ongoing feasibility studies considering the development of technologies. The continued review should account for the latest 1.5-degree-aligned carbon budget and country- and sector-specific decarbonisation pathway, preferably reviewed by a credible and independent third party. The dynamic and comparative assessments inevitably complement the technology-neutral, relatively static thresholds-based taxonomy tools.

Closing use-of-proceeds loopholes

IEEFA believes ceasing new fossil fuel financing, according to the International Energy Agency roadmap, should be the overarching guiding principle for transition finance.

Transition finance with ringfencing requirements will ensure capital flows only to qualified activities. Applying the climate solutions category to entities needs extra care to avoid entities with some non-qualified activities (such as fossil fuel) being eligible without restrictions.

The same principle applies to managed phaseout. The phaseout timing, actions and milestone-linked progress need to be carefully monitored. Any misalignment or phaseout not according to plans could create the impression of a continuation of fossil fuel financing. For example, to support India’s early retirement of coal plants, IEEFA has suggested a sustainability-linked green bond structure, which enables performance-based incentives without compromising use-of-proceeds conditions.

Clearing the boundary of eligible entities

GFANZ defines entities as aligned or aligning if they are in line with or committed to transitioning towards, respectively, a 1.5 degree pathway with additional features of a credible transition plan. Transition finance can reward entities that successfully transition from high-emitting activities, but should specifically encourage those that show meaningful decarbonisation efforts.

Reserving the transition label for a well-defined set of high-emitting, “hard-to-abate” sectors is necessary to facilitate impacts. Instead of defining the scope of assets most in need, GFANZ outlines ways to measure the decarbonisation contributions of these entities. If inherently low-carbon industries fall under this scope, it may raise the risk of incorrect or inadvertently misleading classification. (It is worth noting that general finance—with no climate objectives—should consider forming a 1.5-degree-aligned or aligning portfolio because it might bear lower long-term business risks.)

Sectoral pathways can form a starting point to identify the difficulties that “hard-to-abate” sectors face in decarbonisation. The technical and economic thresholds for these sectors are often evolving and lack guidance. Individual feasibility assessments for the entity’s main activities are a prudent way to pinpoint its eligibility.

Looking out for a credible transition plan

Improving market-led guidance on assessing companies’ transition plans helps FIs determine whether a high-emitting entity is aligned, aligning or not. For example, the Oxford Sustainable Finance Group has suggested ways to evaluate transition plans in emissions-intensive sectors: oil and gas, power generation, steel and aviation. The Climate Bonds Initiative, which is providing certification on transition plans, suggests that a transition plan framework should entail science-based, 1.5-degree-aligned ambition, action and accountability. It has recently drafted sector criteria for electric utilities.

Financing aligning entities—assisting companies in transition from aligning to aligned—may be the very essence of transition finance. However, a loose definition may qualify companies that show no clear timeline of alignment. An aligning entity should demonstrate concrete implementation actions. On this note, the European Union has made an important legislative move through the corporate sustainability due diligence directive (CSDDD) that would require large companies to “adopt and put into effect, through best efforts, a transition plan”. The directive is subject to a final vote.

IEEFA believes FIs should pay attention to transition plans with well-defined timelines and achievement milestones that account for implementation realities. The plans should entail course corrections when proven infeasible or if technology has advanced to a point where a shift is warranted. Also, the progress made in transition to sustainable businesses should be matched with at least an equal progress in winding down the funding of high-carbon activities.

Establishing an FI’s firm-wide transition plan through transition finance

An FI’s transition financing strategy, based on IEEFA’s suggested approaches above, will form part of the FI’s own credible transition plan. These are increasingly subject to regulatory and public scrutiny, in light of the recently launched draft Transition Plan Taskforce sector guidance for financial services and the adoption of European Sustainability Reporting Standards on transition plan information disclosure.

IEEFA believes that rapid regulatory developments on FIs’ transition planning worldwide are key to support transition financing activities. For example, the CSDDD—if successfully passed— would be a breakthrough by requiring FIs to adopt transition plans, although some partial exclusion on due diligence requirements attracted concerns among the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change and Eurosif. In the fourth quarter of 2023, the Monetary Authority of Singapore proposed guidelines on transition planning for FIs, setting out its supervisory expectations.

Shifting capital away from fossil fuels and other non-qualified high-emitting activities

The Science-Based Targets initiative attempted to step up its game on FIs’ net-zero targets, but the pilot version released in November after consultation reflects a weaker-than-expected position, notably towards the phaseout and cessation of new financial flows to unabated fossil fuels. To facilitate a meaningful capital shift towards transition, IEEFA believes that credible transition financing does not work without a clear exclusion and exit strategy with a defined timeframe.

Financing high-emitting assets that are not up to standard will increasingly bear a higher business risk; for asset managers, failing to consider and manage these climate-related risks within their portfolios may be inconsistent with their fiduciary duty. The United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment suggests that “in some cases investors need to address sustainability impacts in order to protect or enhance financial returns”.

For larger, diversified, long-term investors which are invested across all sectors of the economy, the principle of universal ownership foresees that unpriced externalities, such as the socio-economic costs of continued fossil fuel dependency, ultimately will negatively impact portfolio returns, even if they may be artificially boosting returns to some sectors in the near term. These universal owners may have an increasing obligation to adopt more nuanced transition finance approaches to support economy-wide decarbonisation and at the same time restrict flows towards non-aligned activities or entities. This is especially pertinent as the financial system increasingly accounts for a large external cost of carbon emissions (and other externalities such as biodiversity loss) which will be redistributed to polluters over the coming decade (particularly in Europe).

In order to meet net-zero goals, FIs will need to scale up transition finance. The bar is better set high than low—bearing in mind that those not qualified can still get general financing, albeit at a potential risk premium.