Key Findings

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is well-equipped to produce cheap green hydrogen due to its excellent solar resources, but exports look inefficient and expensive.

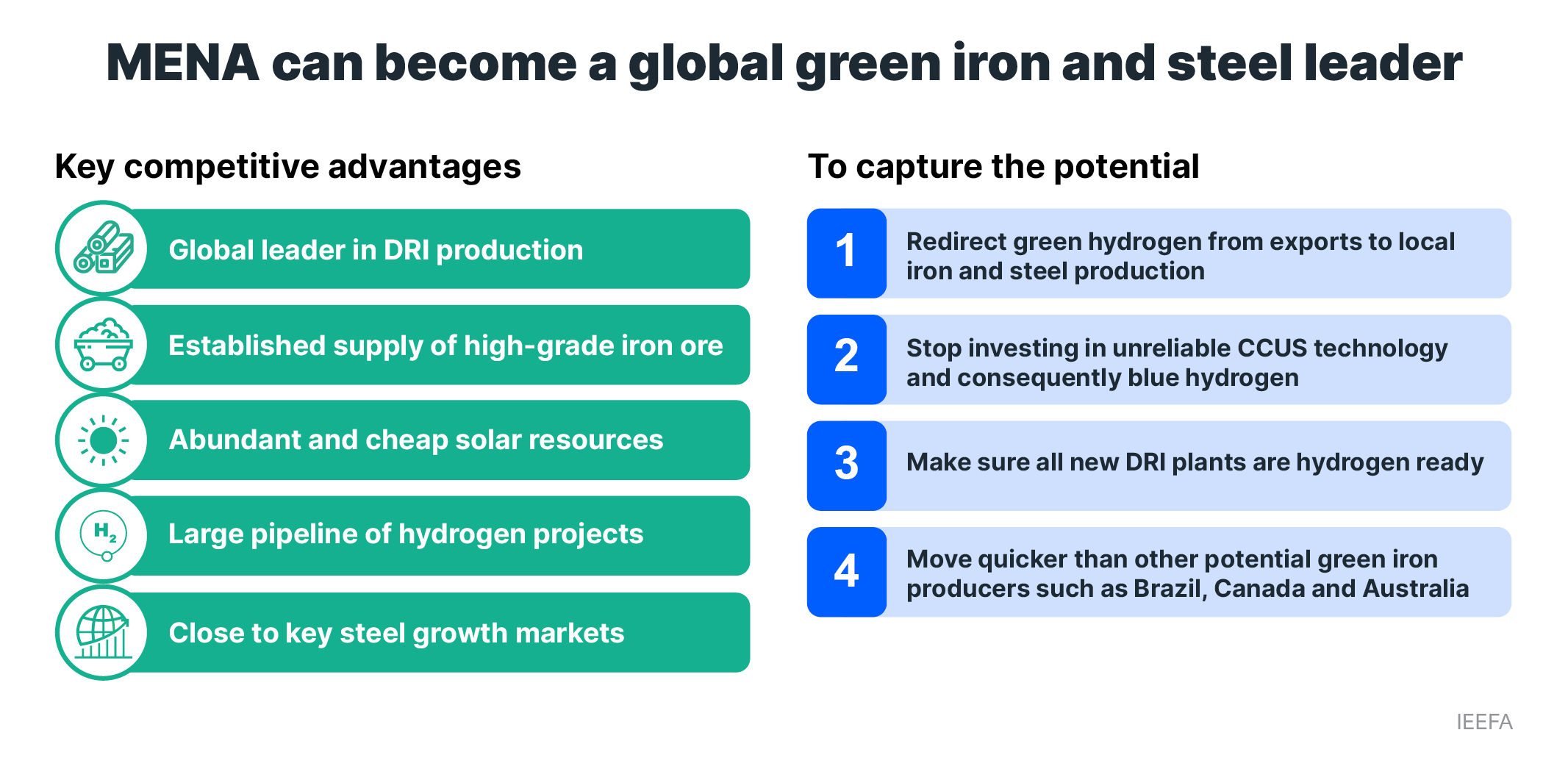

MENA should instead prioritise using green hydrogen domestically to become a global leader in the emerging green iron trade, where it already enjoys a significant advantage due to its established use of direct reduced iron (DRI).

The COP28 climate conference is expected to see widespread advocacy for carbon capture and storage, but the technology’s poor record means it, and consequently blue hydrogen, is not an alternative to green hydrogen.

As the global steel sector decarbonises, the MENA region is well placed geographically to supply the key and emerging markets for green iron and steel. But global green iron competition is already growing.

Executive Summary

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has a significant opportunity to marry its direct reduced iron (DRI)-based steelmaking leadership with its green hydrogen potential. This could place MENA as a global leader in green steel and the emerging green iron trade. The region is well situated to supply the key steel growth market of India and green steel demand centres like Europe.

The steel technology transition is accelerating, and steelmakers are already starting to shift from blast furnace-based production towards DRI technology that can run on green hydrogen. Until now, the focus of steelmakers has been on importing iron ore and metallurgical coal for blast furnaces. Going forward, steelmakers that have access to direct reduction-grade (DR-grade) iron ore and cheap green hydrogen – or the green iron made from them – will have an advantage.

As the global steel sector decarbonises, iron production looks set to dislocate from steel production. More iron ore will be processed in places with excellent renewable energy resources that can produce cheap green hydrogen, with the resultant iron shipped to centres of steel demand. MENA can be a global leader in the emerging green iron trade, but global competition is growing.

MENA’s green steel advantage

MENA’s steel sector has a major advantage as it is already based on DRI using gas rather than coal. The region has an established, growing source of DR-grade iron ore – a commodity in limited supply that makes up just 3%-4% of total global iron ore trade. Vale, the world’s largest producer of DR-grade iron ore, is planning green iron “Mega Hubs” in the Middle East that will supply iron ore pellets to co-located DRI plants to produce hot briquetted iron (HBI) for local consumption and export.

Gas-based steelmaking via DRI has lower emissions than the coal-consuming blast furnaces that dominate steelmaking in most other regions, but it can only be made truly ‘green’ by switching to green hydrogen as its cost falls over the rest of this decade. MENA’s excellent solar resources will allow the region to produce cheap green hydrogen in the near future. Planned green hydrogen production in the region has expanded substantially.

The current focus of green hydrogen projects is on exports. However, exporting green hydrogen appears to be inefficient and expensive. More future green hydrogen production should be earmarked for domestic use to produce green steel. Global steelmakers seeking decarbonisation options will increasingly seek imports of green iron, shipped as HBI. Future DRI-based steel plants in MENA should be built ‘hydrogen-ready’ for conversion to green hydrogen at the earliest opportunity.

As well as Vale, Rio Tinto – the world’s largest iron ore producer – envisages a future where iron ore exports are replaced by exports of green iron as HBI from locations where cheap green hydrogen can be produced. In October 2023, ING’s global steel lead and head of metals, mining and fertilisers stated: “I expect significant iron production to move to places like Northern Europe, Southern Europe and the Middle East and North Africa regions. Steel companies in Europe, Korea and Japan will have to make difficult strategic choices about where to produce iron going forward.”

Steelmakers in South Korea and Japan are already considering the import of HBI from places such as the Middle East, planning projects that would initially use gas before switching to green hydrogen as it gets cheaper. To cut emissions in the interim, some of these projects are considering carbon capture utilisation & storage (CCUS).

Carbon capture should be viewed with scepticism

IEEFA cautions that CCUS increases project risk and has a growing history of significant underperformance. The focus of future MENA iron and steel projects should be on early adoption of locally produced green hydrogen. The Middle East is home to the world’s only industrial-scale steel CCUS project, at Emirates Steel Arkan’s Al Reyadah project in the UAE. However, this does not fully decarbonise the operation – only 30% of carbon dioxide was captured in 2022. The captured carbon is used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) thereby enabling the release of more carbon emissions. EOR will grow increasingly unacceptable to steel buyers, who will increasingly demand green steel and will not want fossil fuels in their supply chains.

Some nations may push for an increased role for CCUS at the COP28 climate conference in November 2023. However, CCUS’s poor track record strongly suggests it is not a key solution for steel sector decarbonisation. A September 2022 IEEFA report found that underperforming carbon capture projects far outnumber successful projects globally, by large margins, with both the technology and regulatory framework found wanting. In its 2023 update to its Net Zero Roadmap, the IEA stated: “The history of CCUS has largely been one of underperformance.”

Concerns about CCUS’s role in steel decarbonisation also apply to production of ‘blue hydrogen’. CCUS proponents often claim or assume high rates of carbon capture are feasible – sometimes up to 95%. However, the historical performance of CCUS across various industries suggest such high capture rates are not even close to achievable on a sustained basis. Potential importers like Japan and South Korea will eventually need to recognise that blue hydrogen is not as clean as is claimed.

Stricter definitions of phrases like ‘green steel’, ‘near-zero emissions steel’ and ‘low-carbon steel’ can be expected in the near future. Although MENA steel production currently has relatively low carbon intensity by global standards, gas-based DRI won’t meet the definition of ‘green steel’ and the like for long. This will also apply to steelmakers employing CCUS either directly or via use of blue hydrogen.

Europe’s carbon price is already seeing it taking a lead in steel sector transformation and green steel demand. A truly low-carbon local steel industry would give MENA further advantage over other regions as Europe’s carbon border adjustment mechanism comes into force. The import of green HBI is likely to be crucial to Europe’s efforts to decarbonise its steel sector, and MENA is ideally placed geographically to supply it. MENA is also well positioned to supply India, the key steel demand growth market globally. Decarbonisation of India’s steel industry will occur later than Europe but likely happen faster than expected given the historical speed of technology transitions.

Global green iron competition is already rising

Despite MENA’s numerous advantages when it comes to developing a truly green steel sector, it faces growing competition from other countries. Its primary competition in the emerging green iron/HBI trade comes from iron ore mining nations – Australia, Brazil and Canada – which all have access to strong renewable and/or hydro power resources.

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of iron ore by far, but the vast majority of its production is of lower-grade, blast furnace-grade ore. Despite this, POSCO is planning a major investment in Western Australia to produce HBI for export, and is co-developing a green hydrogen project to supply it. Japan’s Nippon Steel is also considering a green steel investment in Australia or Brazil. Brazil supplies most of the world’s DR-grade iron ore and has abundant clean energy resources for the production of green steel and HBI. In addition to Nippon Steel, H2 Green Steel is eying Brazil and has agreed with Vale to study the potential for a green iron hub there. H2 Green Steel is also exploring a €3-€6 billion project in Canada, which is also a producer of DR-grade iron ore. Rio Tinto has separately agreed to supply H2 Green Steel’s green steel plant under development in Sweden with iron ore from its Canadian operations.

Early green hydrogen adoption can help meet domestic emissions targets

Growing global competition in the nascent green iron exports sector is further indication that the steel technology transition away from fossil fuels is accelerating. With some nations in the MENA region keen to diversify away from oil and gas, the development of a truly green steel industry is an opportunity to help achieve this. Steelmaking developments in the region should be built hydrogen-ready as far as possible, and the region should make the most of its advantage in low-cost renewable energy by adopting green hydrogen for iron and steel production as quickly as possible.

By moving quicker than other potential green iron producers, the MENA region can become a global leader in green iron exports. The early adoption of green hydrogen can also decarbonise steel made for domestic use.

MENA’s steel sector is already expanding, with numerous plans for new DRI-based plants in Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE that will initially run on gas and transition towards hydrogen on unspecified timelines. Although gas-based DRI is less carbon-intensive than coal-based blast furnaces, this expansion will still add to MENA nations’ domestic carbon emissions at a time when pressure to increase emissions reduction ambition is increasing.

A refocus from green hydrogen exports towards more domestic use can help the region achieve its domestic emissions reduction targets as well as positioning its steelmakers for the global iron and steel sector of the near future.