Australia’s coal production limits far exceed actual output, so why approve new mine developments?

Key Findings

Australia does not need to approve more coalmine expansions to increase annual coal production.

If no additional coalmine projects were approved in Australia, annual production from existing mines could be increased by about 55% or 214 million tonnes to 2050.

Australia’s pipeline of coalmine approvals contrasts with global market outlooks.

Expanding current coalmines increases rehabilitation uncertainty and risks to taxpayers, and could increase Australia’s methane emissions.

The federal government’s latest decision to approve four new coalmine developments fails to account for Australia’s existing coal production capacity and energy export market outlook.

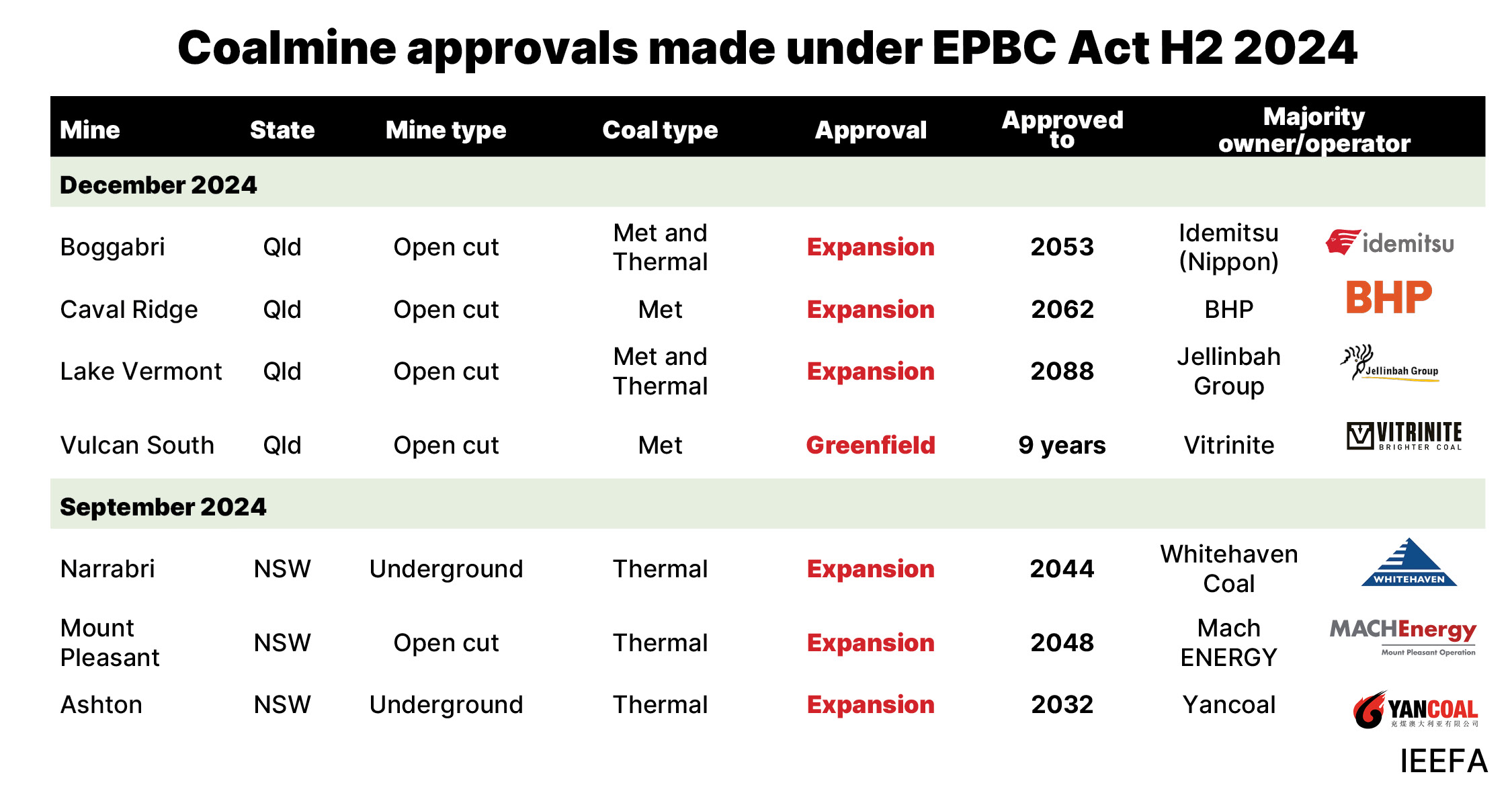

In September and December 2024, the Federal Minister for the Environment and Water approved seven new coal developments. This follows a recent study in Queensland’s Galilee Basin finding that coalmine projects would not be economical due to high costs and shrinking export demand from Asia.

The new approvals range from an additional six years of mining operations to more than 50 years, with three ending in 2053, 2062 and 2088. Granting such lengthy permits severely limits governments’ ability to change licence conditions as new information comes to light – such as more accurate monitoring of methane emissions from coalmining, and uncertainties over long-term water-related impacts and mine rehabilitation costs.

Australia is already sitting on a mountain of approved coal production

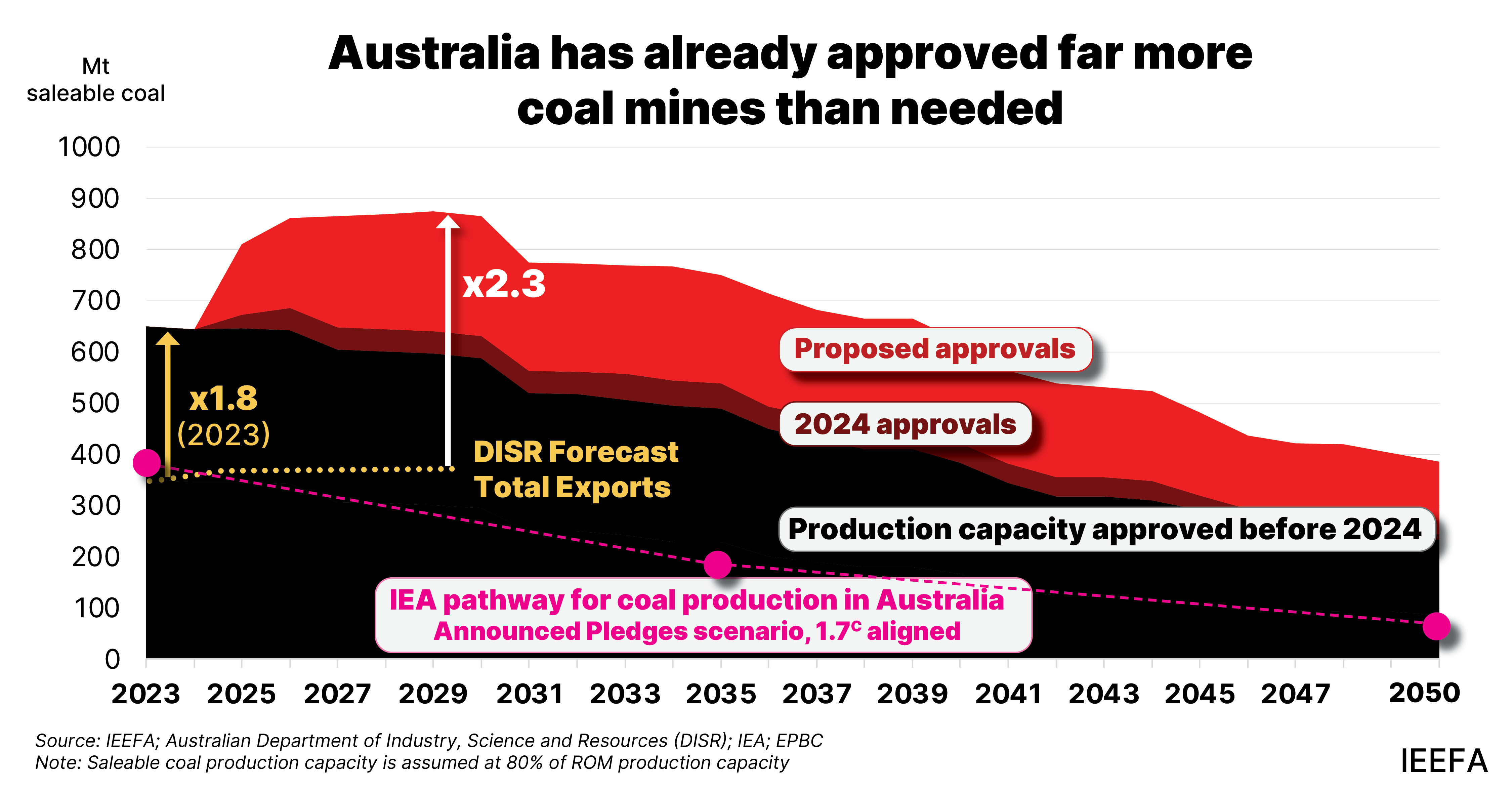

The federal government does not need to approve more coalmine expansions to increase annual production. If no additional coalmine projects were approved, Australia could increase average annual production by about 55%, or 214 million tonnes (Mtpa) run-of-mine (ROM) coal – roughly an even split between thermal (106Mtpa) and metallurgical (108Mtpa) coal – under existing licence production limits in NSW and Queensland (Figure 1). This volume still far exceeds the federal government’s forecast demand from Australia’s coal export markets.

Governments need to decide if they’re prepared for the additional methane and rehabilitation risks of approving further developments.

Figure 1: Australian production capacity saleable coal (approved and proposed) vs export forecasts

Sources: IEEFA analysis; Australian government DISR Resources and Energy Quarterly, March 2024; International Energy Agency; EPBC application documents.

Notes: Approved coal production limits are taken from mine licences and approvals for 111 coalmines in Queensland and NSW. Approved and proposed production volumes calculated based on individual EPBC application documents. Saleable coal production capacity is assumed at 80% of ROM production capacity, a conservative estimate given the average in NSW and Queensland from FY2017-23 was 91%. Production limits apply only to NSW and Queensland. Actual production, export volumes and forecast export volumes include total Australia coal, the majority of which is from NSW and Queensland.

Australia’s coalmine pipeline at odds with global market outlooks

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has stated that no new investments in fossil fuel supply are required to meet future demand under the net-zero pathway to 2050. Contrary to this, Australia has the largest pipeline of coalmines in planning and development of all major coal-exporting countries. According to the latest Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) Resources and Energy Major Projects report, 47 coal projects were in the development pipeline in 2024.

The newly approved projects include thermal and metallurgical (met) coal production. Australia exported more thermal than met coal in 2024, and many of the new coalmine approvals could further expand Australia’s thermal coal production.

The three expansions approved in September 2024 were for thermal coalmines. Of the December 2024 approvals, the Boggabri mine in NSW produces more thermal coal, about 32Mt, than metallurgical (25Mt). Lake Vermont in Queensland also produces thermal coal – about 1Mt in FY 2024.

Source: IEEFA

Australia’s pipeline of coal developments contrasts with other coal-producing nations, which are preparing to reduce production for export in line with demand trends. The IEA’s latest coal report stated that output from Indonesia, the world’s largest thermal coal exporter, was “poised to shrink due to weaker international markets for thermal coal”.

Additionally, there has been no evidence to support the assertion that coal importers will shift towards Australia’s higher-energy thermal coal. The IEA report also highlights the drop in coal imports from Japan, Australia’s largest coal export market, driven by lower coal-fired power generation, along with moderate declines in thermal coal imports from Korea. These declines are expected to continue in line with their national energy strategies. China, India and Indonesia all increased coal production in 2024, with China and India expected to decrease reliance on imports, and Indonesia’s record thermal coal production set to compete with Australian exports.

Over the next three years, the IEA forecasts growth in thermal coal imports will be confined to the Philippines, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Meanwhile, Australian exports to ASEAN countries fell by 7Mt during the first three quarters of 2024. Vietnam, now the world’s fifth-largest coal importer, is looking elsewhere for its coal, with imports of Australian coal declining since 2020. Vietnam plans to increase coal imports from neighbouring Laos tenfold via a planned 6km conveyor belt connecting the two countries. The Philippines increased domestic coal production in 2024, and this could affect its future import demand, while Bangladesh’s import growth may be met in part from neighbouring India.

The argument for these new approvals is that there is long-term demand for Australian coal in global steelmaking, but this is not the case

Metallurgical coal is no longer required to make steel. Recent IEEFA analysis outlines how the accelerating technology transition in global steelmaking risks changing the demand outlook for Australia’s met coal permanently. Steel can, and is, being made without coal around the world already.

While global demand is falling faster for thermal coal than met coal, demand for met coal exports is also set to decrease. The IEA forecasts a 1.9% decrease in global met coal consumption in 2024 compared with 2023, and for this decline to continue through to 2027. Even though met coal consumption is expected to rise in India and Indonesia, the declines expected in China and the rest of the world mean overall global met coal consumption is expected to decline 5.3% in that period.

Approving coalmine expansions could worsen Australia’s methane emissions and pose financial liabilities to taxpayers

As previous IEEFA analysis has found, the deeper miners dig, or the greater the area they blast for coal, the more methane is released. Higher-quality coal and met coalmines also generally emit higher volumes of methane. While the difference depends on specific mine geologies, met coal emits 40% more methane than thermal coal on average in Australia according to the IEA.

As open-cut mine pits become larger and deeper, this can increase the rehabilitation requirements and complexity. To date Australia has no examples of successful rehabilitation of a large, open-cut coal mine.

If a mining operator does not fulfil its rehabilitation requirements, the responsibility and costs of rehabilitation fall on the government and subsequently the taxpayer. Large open-cut mines, which create significant landform alterations, can cost hundreds of millions or billions to rehabilitate.