Key Findings

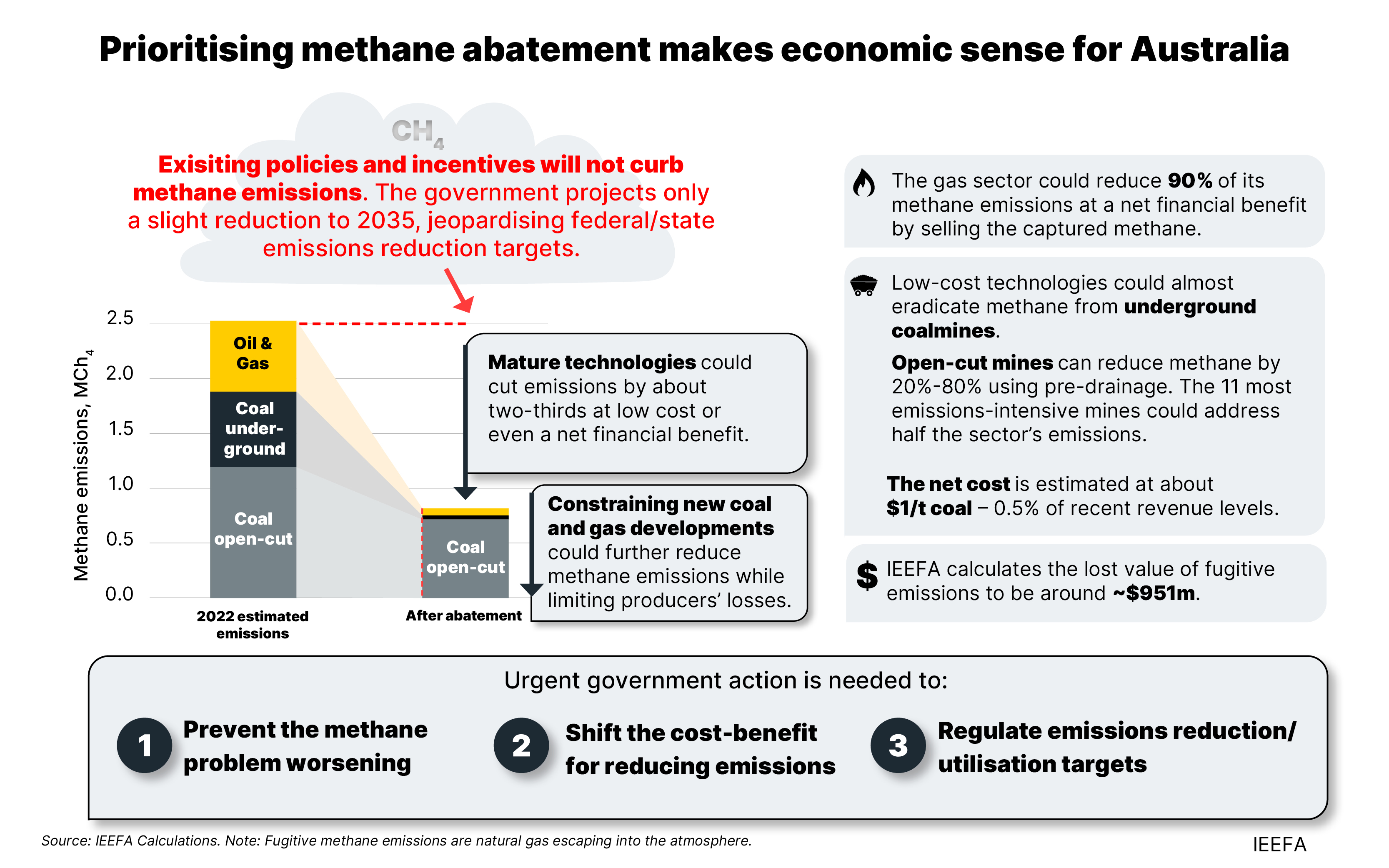

Methane is jeopardising Australia’s emissions reduction targets; it is expected to account for 68%-95% of Australia’s targeted emissions by 2035, 78% of New South Wales’ and even exceed Queensland’s.

Australia could abate two-thirds of its fossil fuel methane emissions using readily available technologies, at a net cost of about A$1 per tonne of coal in coalmining, and at a net financial benefit in the gas sector due to the option to sell the methane captured.

Current policies are ineffective at reducing methane emissions, primarily due to inadequate measurement and settings in the Safeguard Mechanism, with insufficient financial incentives for companies to act.

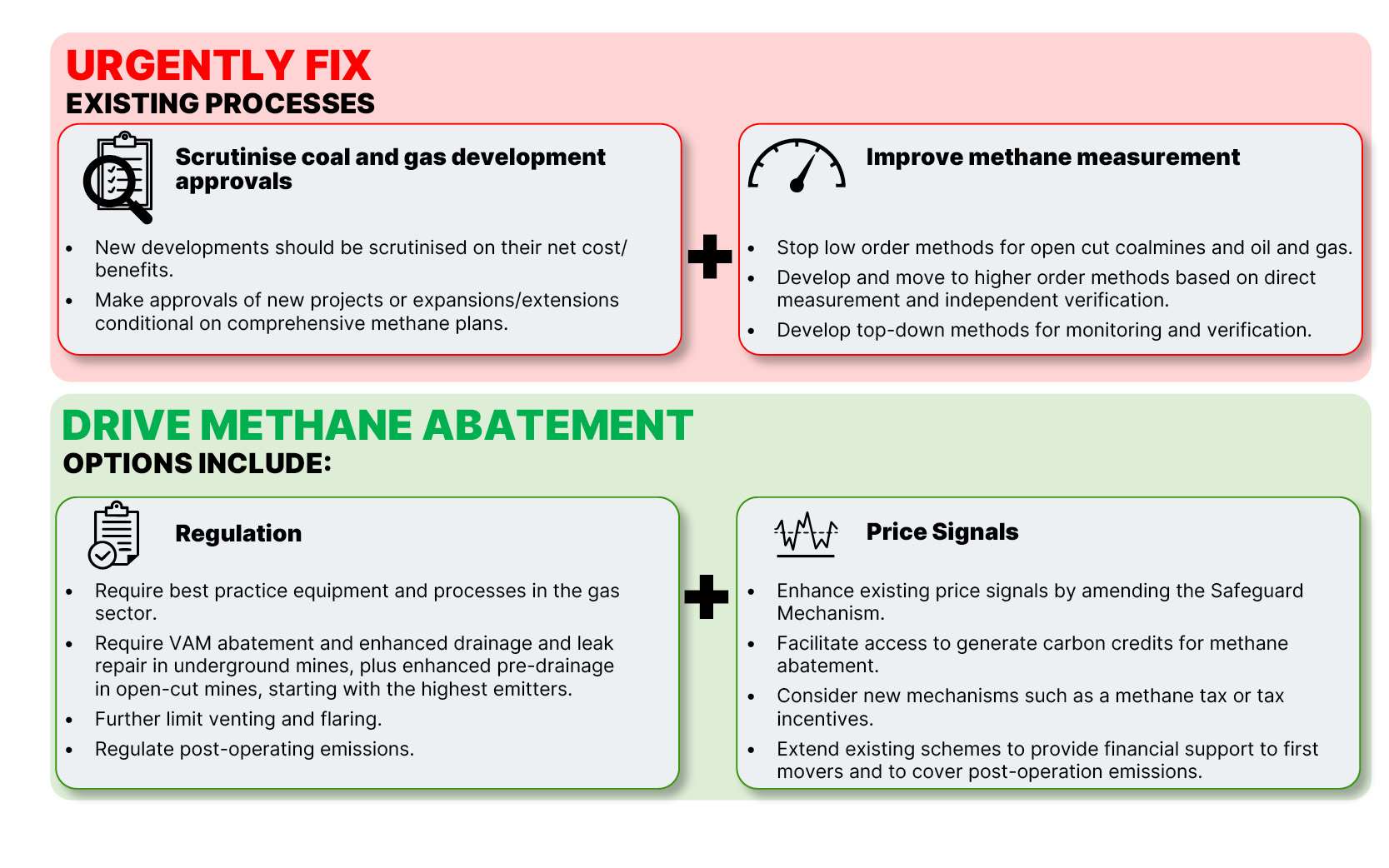

Federal and state governments must act urgently to address the problem, by enhancing financial drivers and regulating for companies to take best-practice methane abatement action.

Executive Summary

Methane has contributed about 30% of the post-industrial increase in global temperatures. Action to reduce methane emissions can provide benefits within decades due to its relatively short atmospheric life and its much stronger warming potential compared with carbon dioxide (CO2).

Australia makes an oversized contribution to global methane emissions due to its high relative production of fossil fuels and agricultural exports. Government projections do not expect methane emissions to decrease materially between now and 2035, while CO2 emissions are expected to halve. Under current settings, Australia’s methane emissions could even increase in that period due to underreporting correction and new fossil fuel developments. This is at odds with Australia’s commitment to reduce methane emissions under the Global Methane Pledge.

It is now well established that methane emissions in Australia are underreported. In many instances, methane emissions are estimated using fixed emissions intensity factors based on the quantity of production, rather than via satellite monitoring, remote sensing or direct measurement. New data providers have found that Australia’s methane emissions have been grossly underreported, particularly from fossil fuel production. The suspected underreporting is particularly high for the gas sector and open-cut coalmines – with some providers suggesting open-cut mine emissions could be nearly six times as high as reported.

Australia’s large pipeline of proposed coal and gas developments could worsen its methane problem. Metallurgical coal production is expected to grow, with metallurgical coal generating more methane than thermal coal. Satellite data suggests we could be vastly underestimating emissions from proposed new projects, providing limited insight into their potential impact at approval stage. In addition, open-cut mining is growing faster than underground mining, which may be in part due to more favourable emissions reporting and Safeguard Mechanism settings for open-cut mines. Given the long lifetimes of new mine developments and extensions, and the fact methane emissions are harder to abate for open-cut mines, this could lock in high emissions for decades and require all other sectors to make faster and deeper cuts to emissions.

As a result, methane emissions are putting federal and state emissions reduction targets at risk. Correcting for likely underreporting, and assuming, as per government projections, that methane emissions remain approximately stable to 2035, they would represent 68%-95% of the indicative targeted emissions by 2035 for Australia, 78% of New South Wales (NSW)’s targeted emissions and even exceed Queensland’s, according to IEEFA’s calculations.

Prioritising fossil fuel methane abatement makes economic sense

The International Energy Agency (IEA) found that reducing methane emissions from fossil fuels has the most potential to quickly reduce overall methane emissions. Two-thirds of emissions can be abated through mature technologies at low cost, or even with financial benefits. Because methane is the main component of natural gas, capturing it means it can be sold or utilised.

In Australia, IEEFA found that 67% of methane emissions from fossil fuels could be abated using readily available technology, at a cost below A$30 per tonne of CO2-equivalent (tCO2e). In the gas sector, the majority of actions would deliver a material financial benefit, so that about 90% of emissions could be reduced at no net cost overall. In the coal sector, potentially 59% of methane emissions could be abated, and the average abatement costs translate to about A$1/t saleable coal across the industry, or approximately 0.5% of recent income levels. In addition, underreporting means methane reduction costs may have been overestimated to date.

While open-cut mines typically emit less methane than underground mines per unit of coal produced, their sheer volume means they represent the majority of Australia’s coalmine methane emissions.

In underground coalmines, methane is already pre-drained from coal seams before operations, but the amount pre-drained could increase. Most underground methane emissions are generated by ventilation air methane (VAM), the air from the underground mine shaft that must be ventilated for safety reasons. The main opportunities to reduce methane emissions from underground mines are to: abate VAM, detect and repair leaks to increase the volumes of methane captured in pre- and post-drainage, prevent venting and regulate flaring, and enhance post-mining capture, which can also support communities facing mine closures.

In the vast majority of open-cut mines, no action is taken to capture methane. Open-cut mines can reduce methane emissions via methane pre-drainage or reducing production. While pre-draining technology is readily available, the industry asserts that it is too difficult or costly to employ. Recent examples suggest that with the right policy settings, it is financially feasible. The emissions intensity of open-cut mines varies widely, and targeting high emitters first could deliver high reductions.

In the gas sector, methane is emitted through the entire supply chain, with about two-thirds coming from production and one-third from transmission, distribution and storage. About 90% of methane emissions could be abated through best-practice equipment and processes, at a net financial benefit overall since the recovered methane can be sold in domestic and international markets.

These cost-effective solutions could also alleviate tight domestic gas supply in Australia. IEEFA calculates about 76 petajoules (PJ) of methane could be recovered across the coal and gas sector – more than twice the amount of gas anticipated to be required for power generation in the National Electricity Market in 2025. This represents a lost value of about A$951 million.

Reducing production is the only method that allows for a 100% reduction in methane emissions, especially from open-cut coalmines. In scenarios aligned with 2.4°C and 1.7°C of global warming respectively, the IEA expects global coal production to fall by 30% or 50% by 2035, with Australia facing similar trends. It also estimates that global LNG markets will face an enormous supply glut, pushing prices to below production costs if LNG markets are to absorb the new supply. IEEFA analysis has shown that many proposed coalmines and gas fields are unlikely to be profitable, and the financial situation of existing projects could worsen.

Policies ineffective at driving action

Fossil fuel methane emissions appear to have risen under the Safeguard Mechanism, whose shortcomings limit its effectiveness at driving reductions. In addition, while methane abatement projects are eligible to earn revenue via the Australian Carbon Credit Unit (ACCU) scheme, this is not attracting investment. Overall, the financial incentives are insufficient to drive company action. The lack of clarity over companies’ actual emissions makes it harder to develop a business case for their reduction. Companies also face capability gaps, and prioritise other, more profitable uses of capital.

Australia lags other major fossil fuel producers – the US, China and the EU – in its adoption of effective methane abatement technology. Government intervention is urgently needed to tackle the problem, and address market failures. The figure below summarises IEEFA’s recommendations for governments at federal and state levels. Experience in other regions shows that a combination of price signals and regulation can be effective at driving comprehensive action to reduce methane.

CORRECTION: This report was amended on 15 April 2025. On P.32, the estimates in Table 1 have been updated to reflect pricing for calendar year 2024. Report references have been amended accordingly.