Key Findings

The Australian government has approved four new metallurgical coal projects amid falling international demand and a declining long-term outlook for exports of the commodity.

Iron ore prices are expected to fall significantly amid new supply and declining steel demand in China. Longer term, Australia's biggest export is exposed to growing demand for higher-grade iron ore suitable for low-carbon steelmaking.

Efforts to make Australia's lower-grade iron ore suitable for low-carbon steelmaking are essential. But with international rivals eyeing the production of iron using green hydrogen, Australia must not get diverted towards gas and blue hydrogen by fossil fuel interests.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

As 2024 ended, it became increasingly clear that earnings from Australia’s biggest export – iron ore – are set for significant decline. And just before Christmas, the Australian government approved four new metallurgical coal projects in a market facing deteriorating volumes.

Falling steel demand in China is largely responsible for these near-term impacts but, in the longer-term, steel technology changes risk altering demand for Australian iron ore and metallurgical coal permanently.

Federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek’s rationale for approving the new coal projects was: “There are currently no feasible renewable alternatives for making steel.”

And federal Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen stated, “I'd like an explanation as to how you can make steel without coal at the moment.”

That’s an easy one – plenty of steel is made without coal around the world already. Truly green steel made with green hydrogen is also on its way at commercial scale. Stegra’s under-construction green steel plant in Sweden will begin commercial operations next year.

Around the same time the coal projects were approved, the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) annual coal report forecast that “met coal imports, of which Australia is the largest exporter by far, are expected to shrink” over the next few years, with Australia’s exports forecast to decline.

This is in contrast to the Department of Industry, Science and Resources’ (DISR) December Resources and Energy Quarterly report, which again forecast increased Australian metallurgical coal exports despite actual imports declining for the past five years.

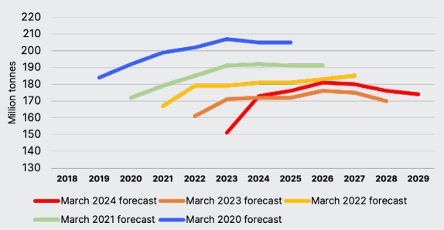

DISR has an history of overestimating Australia’s metallurgical coal exports (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Australian government metallurgical coal export forecasts 2020-2024

Source: Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Australian government

Iron ore impacts

DISR’s latest quarterly report also contained sombre news for iron ore. Despite growing volumes, declining prices mean Australia’s iron ore export earnings will fall by A$42 billion over two years, with benchmark iron ore prices forecast to drop to US$76 per tonne from about US$100/t now.

This short-term decline will be driven by growing supply from Australia and Brazil in the face of softening demand from China – by far the world’s largest importer. From 2026, the impact of further new supply from the Simandou projects in Guinea risks dampening prices even further.

However, longer-term Australia is at further risk from a shift in demand towards higher quality, direct reduction-grade (DR-grade) iron ore currently needed for the only credible route to truly low-emissions steelmaking via direct reduced iron (DRI) processes.

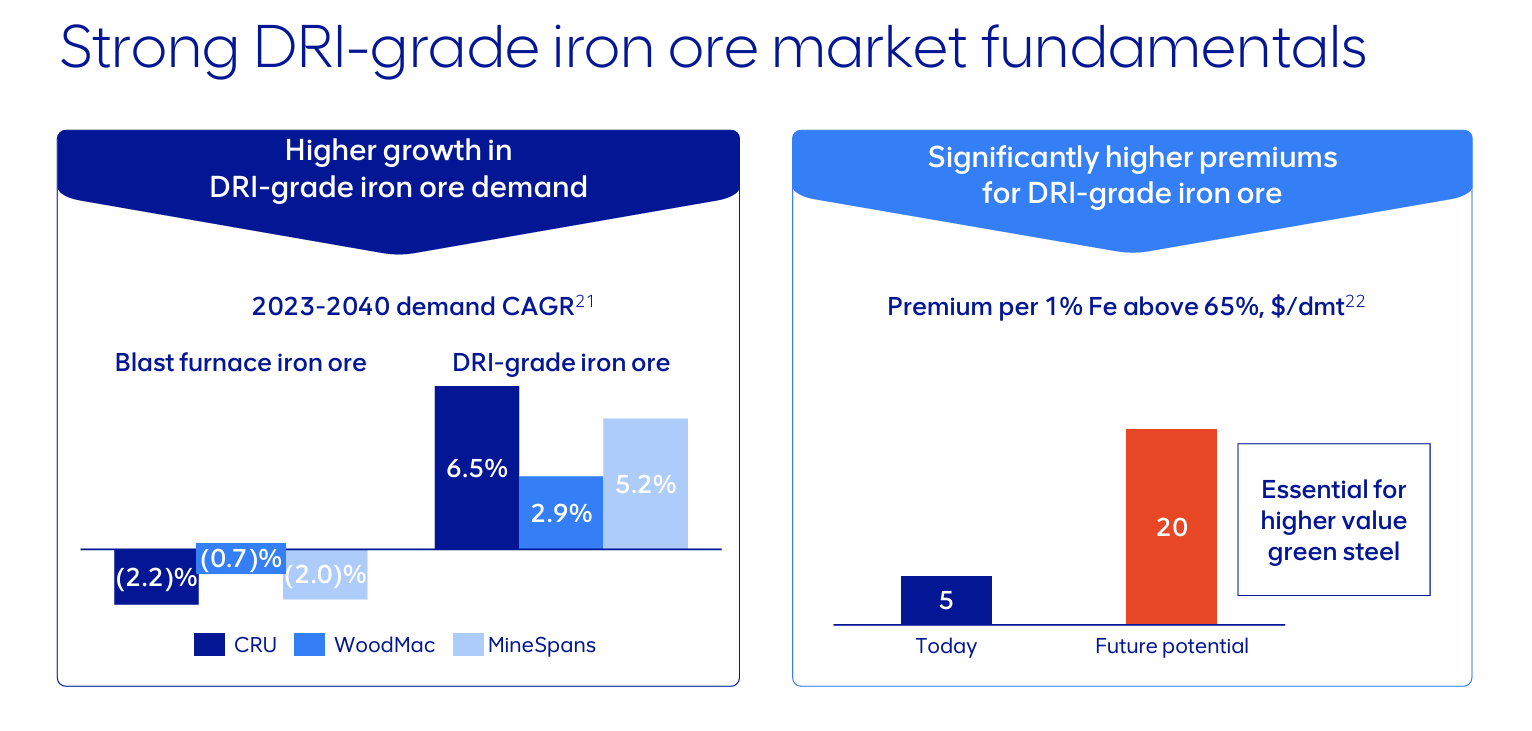

Anglo American has highlighted industry forecasts of strong demand growth for DR-grade iron ore as demand for blast furnace-grade ore goes into decline (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Anglo American’s summary of long-term iron ore forecasts

Source: Anglo American

Australia could increase production of DR-grade iron ore, and South Australia has a nation-leading opportunity to turn its high-grade ore into green iron for export. However, almost all of Australia’s iron ore exports are well below DR-grade.

This is why efforts to make Australia’s lower-grade ore usable in DRI-based steelmaking processes are so important. The long-term future of Australia’s largest export depends on it.

One of the most prominent projects seeking to achieve this is the collaboration between Rio Tinto, BHP and BlueScope on the NeoSmelt project, but the most recent progress update included a worrying element.

Collaboration with Woodside drags Rio, BHP and BlueScope in the wrong direction

The entry of Woodside into the project last month reaffirms that gas is being targeted as the DRI reductant in the NeoSmelt project.

Internationally, many of Australia’s potential competitors are targeting the use of green hydrogen to make truly green iron and steel. In many cases, overseas iron and steelmakers will start DRI operations on gas before switching to green hydrogen as it gets cheaper. That looks unlikely to be on Woodside’s agenda.

The latest project update states that, “It will initially use natural gas to reduce iron ore to DRI, but once operational, the project aims to use lower-carbon emissions hydrogen to reduce iron ore.”

“Lower-carbon emissions hydrogen” suggests blue hydrogen made from gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS), not zero-emissions green hydrogen. The multiple issues affecting CCS – including low capture rates – mean blue hydrogen cannot be considered low in emissions.

In the longer-term, blue hydrogen-based iron and steelmaking won’t be able to compete with truly green iron on both emissions and cost.

Meanwhile, it is also clear that the South Australian government’s plan to develop a new DRI plant in the state is coming under pressure from the gas industry. This is despite the state’s huge advantage in renewable energy – targeting net 100% renewable energy by 2027 – that puts it in an enviable position to produce green hydrogen competitively in the future.

Fortescue has dismissed the use of gas in DRI, and is focused on green hydrogen. In Brazil, Vale – the other member of the “Big 4” iron ore producers – announced this month that it is working with Sweden’s GreenIron on the feasibility of DRI plants in both nations and the potential role of green hydrogen. Vale is already exploring opportunities for green hydrogen production in Brazil.

Nations such as Canada and Oman also have major opportunities to compete with Australia in the rapidly evolving iron sector by making truly green iron using green hydrogen.

Steelmaking technology is changing. Markets for Australia’s iron ore and coal will start looking very different sooner than most expect. Australia needs to keep up with growing competition overseas by targeting the replacement of gas with green hydrogen to reduce its iron ore as soon as possible, not getting diverted towards permanent gas use by fossil fuel interests.