Key Findings

With significant new supply of iron ore coming online over the next few years, the global market will enter a period of major oversupply later this decade, with reduced prices and revenues for Australia’s biggest export.

Meanwhile, it’s becoming ever more apparent that iron ore demand in China – which makes most of the world’s steel – is in decline.

An accelerating steel technology shift adds a further challenge for Australian iron ore producers.

Now is a good time for Australia to seriously think about what its iron ore sector needs to look like in the long term.

This analysis is for information and educational purposes only and is not intended to be read as investment advice. Please click here to read our full disclaimer.

Multiple long-term threats to Australia’s biggest export are now growing.

Rio Tinto’s approval of its Simandou project in Guinea is the largest part of a wave of new iron ore supply coming online in the next few years. At the same time, it’s becoming ever more apparent that China’s iron ore demand is in decline now that it is past peak steel demand.

China will also seek to recycle more steel going forward, further reducing iron ore demand from the country that produces most of the world’s steel. As a result, the global seaborne iron ore market is about to enter a period of significant oversupply and lower prices.

On top of this, the steel technology transition from blast furnaces to direct reduced iron (DRI)-based steelmaking will shift the demand profile towards higher-grade iron ore.

Simply digging and shipping has worked very well for Australia in recent decades. But now is a good time for Australia to seriously think about what its iron ore sector needs to look like going forward.

China: Past peak steel and iron ore demand

China’s steel demand has already peaked and entered decline, which will result in reduced iron ore demand from the nation that currently imports 76% of traded ore. China’s steel emissions look like they peaked in 2020 – ten years ahead of schedule.

On top of this, steel technology change will further reduce its iron ore imports.

Around 90% of steel production in China is made via the coal-consuming blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) process, with only 10% made from recycling steel in electric arc furnaces (EAFs).

However, earlier in July the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) reported a potential turning point in Chinese steel decarbonisation. In the first half of 2024, no new coal-based steelmaking capacity was permitted for the first time since 2020. Only new EAFs were approved.

China is intending to increase its proportion of steel made in EAFs from 10% currently to 15% in 2025, with further growth to come. This shift will help to reduce China’s steelmaking emissions as the scrap-EAF process does not use metallurgical coal. However, there is another benefit for China – it reduces its reliance on imports from Australia.

With scrap steel set to become more available as the Chinese economy matures, the China Iron and Steel Association foresees that 30% of Chinese steel production could come from the scrap-EAF process by 2035. This on its own would account for a significant reduction in imports of both iron ore and metallurgical coal – Australia is the world’s largest exporter of both.

Meanwhile, demand growth for iron ore in emerging Asian markets looks set to disappoint. With Chinese steelmaking in decline, the likes of India and Southeast Asia were supposed to fill the demand gap for iron ore and metallurgical coal. However, S&P Global analysis suggests that only a quarter of the expected 100 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of additional steel production across India and Southeast Asia can be expected to be built by 2030.

India is targeting 300Mtpa of total steel capacity by that date but, even though steel demand is growing significantly, it is not fast enough to reach this target. The Australian government’s latest Resources and Energy Quarterly (REQ) report forecasts Indian steel production at 166 million tonnes (Mt) in 2026 with a growth rate of 5.2% – not fast enough to reach 300Mt by 2030. India is currently self-sufficient for iron ore, but Australian metallurgical coal exporters also look likely to be disappointed.

Iron ore market heading for major oversupply this decade

Just as Chinese iron ore demand falls, supply is set to significantly increase.

Iron ore major Vale is intending to bring an additional 50Mt of supply online in Brazil over the next two years. Mineral Resources’ Onslow project delivered its first ore ahead of schedule in May this year and will ramp up to 35Mtpa.

But the biggest source of new supply will come from the Simandou projects being opened up by Rio Tinto and a group of Chinese developers including China Baowu, the world’s largest steelmaker. Starting in 18 months, supply from these mines is expected to ramp up to 90Mtpa by 2028 according to Macquarie Bank, before continuing to 120Mtpa.

This new supply combined with declining demand in China will place the iron ore market in significant oversupply. Macquarie Bank forecasts a surplus of 200Mt over the 2026-2028 period. Depending on how the Chinese steel industry fares, it could be even more.

There will clearly be an impact on iron ore prices and the value of Australia’s exports. The latest REQ report forecasts iron ore at US$77/tonne in 2026 (down from US$105-US$110 now). Macquarie Bank sees iron ore prices down to the US$70s or even US$60s before the end of the decade. Commonwealth Bank of Australia forecasts a long-term iron ore price of US$68/tonne.

Large-scale production from the likes of Rio Tinto, BHP and Fortescue will remain healthily profitable at these prices, but Australia will see significantly reduced revenues. And from the end of the decade, a shift in steel technology will be even more apparent, with implications for the iron ore market from then on.

Iron ore’s demand profile set to change in response to steel decarbonisation

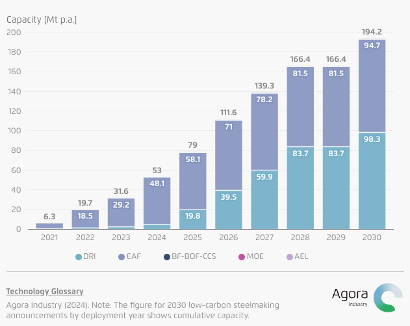

The current pipeline of announced low-carbon steel projects sees nearly 100Mt of new DRI capacity coming online by 2030 (Figure 1). China already has two commercial-scale DRI-based steel plants up and running. DRI plants can run on green hydrogen rather than gas to produce truly low-emissions iron and steel, but they currently require a higher grade of iron ore than the great majority of Australian production.

Figure 1: 2030 pipeline of announced low-carbon steelmaking projects (by deployment year)

This will result in a significant increase in demand for direct reduction-grade (DR-grade) iron ore, which currently makes up only about 5% of the global seaborne iron ore market. Both Vale and Anglo American – which both produce iron ore of a higher grade than the great majority of Australian production – see a supply shortfall of DR-grade ore by 2030, and both are intending to fill that gap.

Rio Tinto looks likely to join them. Rio has previously disclosed that the Simandou deposit has an estimated 40% of iron ore resources that are “potentially well suited to meet the DRI specification, which could be processed via the lower-carbon DRI-EAF route”.

With almost all of Australian iron ore production below DR-grade, a shift towards mining more magnetite iron ore, which can more easily be processed to the higher grade currently needed for DRI, is on the cards.

With green hydrogen exports looking structurally expensive, there is an opportunity to process Australian high-grade ore, using domestically produced green hydrogen, into ‘green iron’ for export to steelmakers globally. South Australia is now leading nationally with its new Green Iron and Steel Strategy and the launch of an Expressions of Interest process for a new DRI project using the state’s high-grade iron ore reserves.

The federal government’s Future Made in Australia agenda is also targeting the production and export of green iron.

However, major steelmakers are often resistant to the idea of importing iron from overseas. European steelmakers are receiving funding from governments to transition their operations from blast furnaces to DRI domestically, not to see ironmaking relocated overseas. Asian governments may also be reluctant to see their steelmakers relocate ironmaking offshore.

With carbon capture for steelmaking going nowhere, at least some relocation of ironmaking to places where green hydrogen can be made at a competitive cost looks increasingly likely to be needed if the steel sector is going to wean itself of coal and gas.

Australia is well placed to become an exporter of green iron in addition to iron ore, but federal and state governments need to make sure there are markets for it overseas. This may require working with the governments of major steelmakers like China, Japan and South Korea, but also those of emerging Asian nations.

A revenue hit is approaching for Australia’s biggest export, and there is growing international competition in the high-grade ore and green iron space. Australia needs to seriously consider, and plan for, what its iron ore sector needs to look like from the next decade onwards.