IEEFA Update: The U.S. Energy Information Administration Continues to Miss the Mark

The Energy Information Administration, the federal agency responsible for national energy data compilation and analysis, has been historically out of sync on its U.S. coal-industry projections and seems every bit as off the mark as ever these days.

It’s as if the EIA can’t quit going rogue from reality.

In a “Today in Energy” article published on the EIA website on March 30, the agency—which is funded by taxpayer dollars—discusses its logic-defying forecast, part of its “Annual Energy Outlook 2018,” on how it envisions coal’s future role in the U.S. electricity-generation equation.

The agency says it sees “virtually no [coal plant] retirements from 2030 through 2050,” an assertion that flies in the face of well-established trends. While coal will remain a component of the American electricity-generation mix, its share of the market is in decline and will very likely remain so for years to come.

As IEEFA noted in a January report, “U.S. Coal: More Market Erosion Is on the Way,” the purported comeback of the industry in 2017 is often overstated “and its trend toward long-term structural decline is all but sure to persist.”

Momentum toward a cleaner, cheaper electricity-generation sector is only growing, driven by market forces, by preferences among consumers and businesses, and by the utility industry itself. The trend is not toward more coal-fired generation capacity—which is an assertion at the heart of the analyses that the EIA puts out—but less of it.

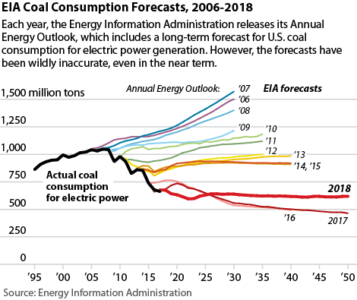

How far off are the EIA’s forecasts? In its 2007 Outlook, the agency predicted that coal consumption for electricity in 2017 would total 1,209 million tons. Last year’s actual consumption: 663 million tons. And that was a forecast that went only 10 years out. The agency’s latest forecast goes 30 years into the future. The chart here illustrates how out of whack the agency’s forecasts are.

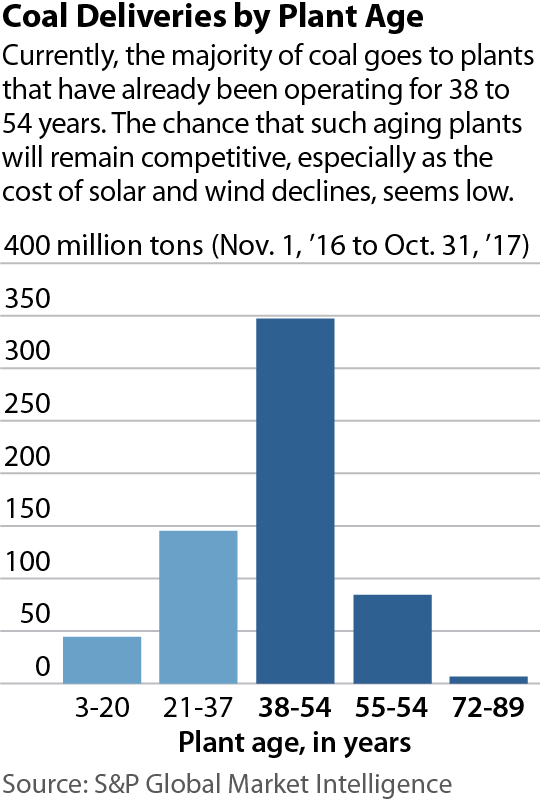

That EIA’s flat-line projection, in which it concludes that national coal consumption will remain consistent through 2050, ignores the facts, one of which is that the U.S. coal-fired generating fleet is old. According to the EIA’s own data, 88 percent of the nation’s coal capacity was built before 1990, meaning that by 2050 the youngest plants, assuming they are still running, would be 60 years old, which is to say they would have exceeded their life expectancy. EIA’s most recent raw data has the current 2017 U.S. coal fleet’s capacity-weighted age—which accounts for the size of the plant and the year it became operational—at 39 years. The data snapshot below, from S&P Global Market Intelligence, is a good indicator of the overall age of the fleet.

The agency is silent on the fact that no coal plant has been built in the U.S. in years and that no more are likely to be built.

IN ANOTHER BIZARRE LEAP OF LOGIC, THE EIA HAS THE AVERAGE CAPACITY FACTOR of U.S. coal plants increasing somehow to 70 percent—a level not seen since the mid-2000s, when the fleet was much younger —and then maintaining that performance through mid-century.

There are two major problems with this projection. First, it omits the effects of inevitable age-related deterioration. Second, it fails to acknowledge fundamental shifts sweeping the utility sector, notably the surge of new renewable generation resources that have no fuel costs and the shale boom that has pushed natural gas prices down and that will most likely keep them low for the foreseeable future.

A bit of history is helpful here. In 2005, U.S. coal plants by and large were operated as baseload facilities, running essentially 24/7 all year. Roughly 270 plants that year posted capacity factors of 70 percent or higher. By 2015, the paradigm had shifted, and fewer than 100 plants recorded capacity factors of 70 percent or better (a plant’s capacity factor is the power it produces as a percentage of its potential).

Markets have shifted, as vividly illustrated by the surge in recent years of wind generation in the Midwest. Because wind-powered electricity has no fuel cost, it is dispatched ahead of power produced by the coal-fired plants that once dominated. Last year in the region, 10 states from Texas to North Dakota generated at least 10 percent of their power from wind, and four — Iowa, Kansas, Oklahoma, and South Dakota — generated more than 30 percent.

The trend is not to maintain current coal-fired generation capacity—the assertion at the heart of the analyses that the EIA puts out—but to curtail it.

Given what’s happening broadly in American electricity markets, cranking up the U.S. coal fleet back to where it would be operating at a 70 percent capacity factor is a pipe dream.

Many utilities have already released plans to drastically reduce or eliminate coal from their generation mix. In fact, two of the largest utilities in the South, where wind resources are more limited than in the West, just released reports on how they plan to drastically cut carbon emissions by 2050.

Duke Energy expects to shut nine more coal-fired generating units, with a total capacity of two gigawatts, by 2024. The company has slashed coal’s share of its generation mix from 58 percent in 2005 to 33 percent in 2017, and will cut it in half again, to just 16 percent, by 2030.

Southern Company says it has set an even higher goal: eliminating nearly all greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 — an astonishing turnaround for a company that sank nearly $8 billion over the past decade into a “clean coal” power plant experiment that ended in failure and now runs on natural gas. Both companies, like many others, are planning to add large amounts of solar and wind.

Wishing something doesn’t make it so, and those in search of accurate analysis of what’s really going on in the U.S. coal industry apparently aren’t going to find it at the EIA.

Dennis Wamsted is an IEEFA associate editor. Seth Feaster is an IEEFA data analyst.

RELATED ITEMS:

IEEFA Update: Why Investors Are Watching the Navajo Generating Station Story So Closely

IEEFA Update: A Growing Consensus on Transition

IEEFA Update: America’s Coal Industry Is in Trouble