IEEFA update: Out-to-pasture coal plants are being repurposed into new economic endeavors

One of the questions dangling around the closure of the Navajo Generating Station (NGS) in northern Arizona is what will become of the site once the plant shuts down at the end of 2019.

One of the questions dangling around the closure of the Navajo Generating Station (NGS) in northern Arizona is what will become of the site once the plant shuts down at the end of 2019.

One option being discussed is turning NGS into a utility-scale solar and/or storage power site. As part of the plant retirement deal between the Navajo Nation and the plant’s utility-company owners, the tribal government has access to 500 megawatts of transmission capacity on lines that, since the mid-1970s, have been sending power out to distant cities.

Redeveloping NGS as a utility-scale sun-powered station or hub that feeds into those lines would dovetail neatly with fast-evolving public policy in the region and with electricity-generation market modernization. The Salt River Project (SRP), which has an annual operating budget of $3 billion and about one million power customers in the Phoenix area, holds the biggest stake (42.9 percent) among the five owners of NGS. Just this week it published a set of “sustainability goals” that include “more aggressive measures to reduce carbon emissions” and that aim to “strengthen the grid to allow more customer choice.”

A 500MW solar retrofit of NGS would serve those goals well—in Arizona, a single megawatt of solar will power 150 homes, even without taking into account the fast-growing advancement of storage technology that is driving that ratio up.

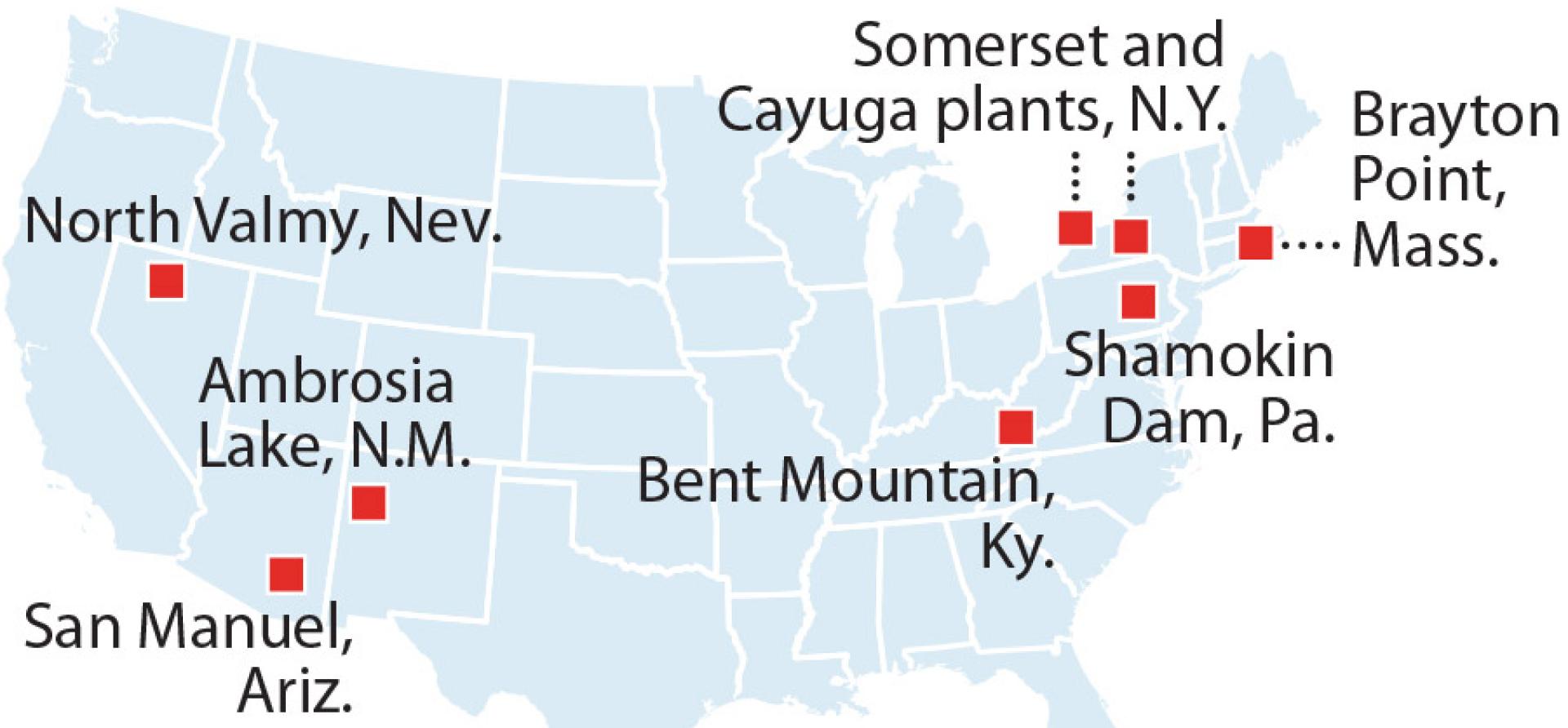

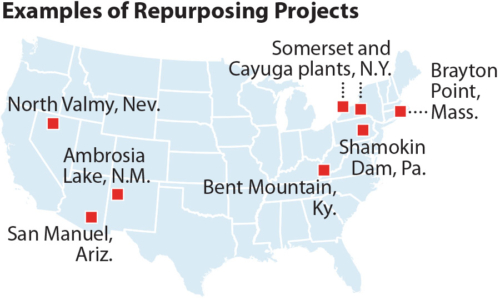

THE IDEA OF REDEVELOPING OLD COAL-FIRED PLANT SITES IS CATCHING ON NATIONALLY as the new electrification economy takes root. More than 300 coal plants have been shut down since 2010 and many more closures are to come, leaving behind sites that can be repurposed in numerous ways that support local and regional economic diversification.

Old assets transformed from energy suppliers into energy consumers.

In New York, the owner of the Cayuga and Somerset coal-fired power plants is considering a $100 million changeover that would repurpose the sites into data centers, transforming them “from energy suppliers to energy consumers.” The Cayuga project is notable because it results from a recent decision not to retrofit the coal plant as a gas-fired generator, an acknowledgement of market realities and public policies and preferences that favor renewables.

The former site of the coal-fired Brayton Point Power Station in Massachusetts is being redeveloped to the tune of $650 million into the Anbaric Renewable Energy Center, a logistics hub and port base for the region’s emerging offshore wind industry.

In March, Idaho Power announced that it would use transmission lines connected to the retiring North Valmy coal-fired plant in Nevada to hook into a new 120MW solar farm south of Twin Falls (utility-scale solar has become a competitive source of power and a money-maker).

Pennsylvania has lost 14 coal plants and, in response, has rolled out an initiative to repurpose nine of them, including one as a medical marijuana farm in the east-central part of the state. The project is part of the redevelopment of the old Sunbury power generation site at Shamokin Dam on the Susquehanna River that might also include a warehouse and a data center.

In every instance, the inherent advantages of power generation station location are being emphasized, much as IEEFA has done in research around NGS repurposing possibilities, but perhaps no better stated than by Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf two years ago in noting how “operational coal-fired power plants are very often in prime locations for redevelopment, boasting access to excellent existing infrastructure assets like rivers, highways, railroads, and utilities.”

“In addition to offering developers confidence in estimating potential project budgets, this effort is also likely to facilitate negotiations and transactions with plant owners,” Wolf added. “Efficiently returning these sites to the tax roll benefits surrounding communities and enhances the overall well-being of the commonwealth.”

SIMILAR REPURPOSING IS OCCURRING AT MINING SITES, as in the case of the Bent Mountain coal mine in eastern Kentucky, which is ceasing production in a few weeks. EDF Renewables, a global company with dozens of U.S. projects in play, plans to turn Bent Mountain into a utility-scale solar farm if it can secure government approval.

BHP, another energy industry behemoth, is buying development rights to the Ambrosia Lake uranium site in northwestern New Mexico with the intention of installing utility-scale solar (BHP has similar plans for the former San Manuel copper mine complex in southern Arizona).

Efforts to repurpose abandoned power sites are surfacing internationally as well, such as with Genex Power Ltd. in Australia, which is vastly expanding a solar farm it has set up at the defunct Kidson Gold Mine and is adding wind and hydro-storage components, pushing the complex’s total electricity-generation capacity to more than 700 megawatts.

A poignant example of the old-turned-new in recent months is the installation of a small solar farm at Chernobyl, a joint project of German and Ukranian investors, that produces enough electricity to power 2,000 households near where the catastrophic nuclear-reactor meltdown occurred, in 1986.

The stress on coalfield communities created by the transition under way in the U.S. electricity industry and globally need not be a one-way street to nowhere. It presents opportunities for redevelopment and new uses that can contribute significantly to local economies, given supportive policies and bold leadership.

Karl Cates ([email protected]) is an IEEFA research editor.

Seth Feaster ([email protected]) is an IEEFA data analyst.

Related items:

IEEFA U.S.: Imminent Hopi-Navajo budget crisis as coal industry collapses

IEEFA U.S.: Solar-plus-storage is undermining the economics of existing coal-fired generation

IEEFA U.S.: Solar tax credit extension through 2024 critical for coalfield communities