IEEFA U.S.: Plastics tax debate is health and safety issue for rest of U.S.

The debate in Washington over taxing virgin plastics is worth watching. The issues are much bigger than a tax-aggrieved industry versus a government in need of cash for new investments.

It is more than the American Chemistry Council, which opposes a tax, versus Democratic leaders like U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse and Rep. Tom Suozzi, who support a tax.

Prices are way above where they should be

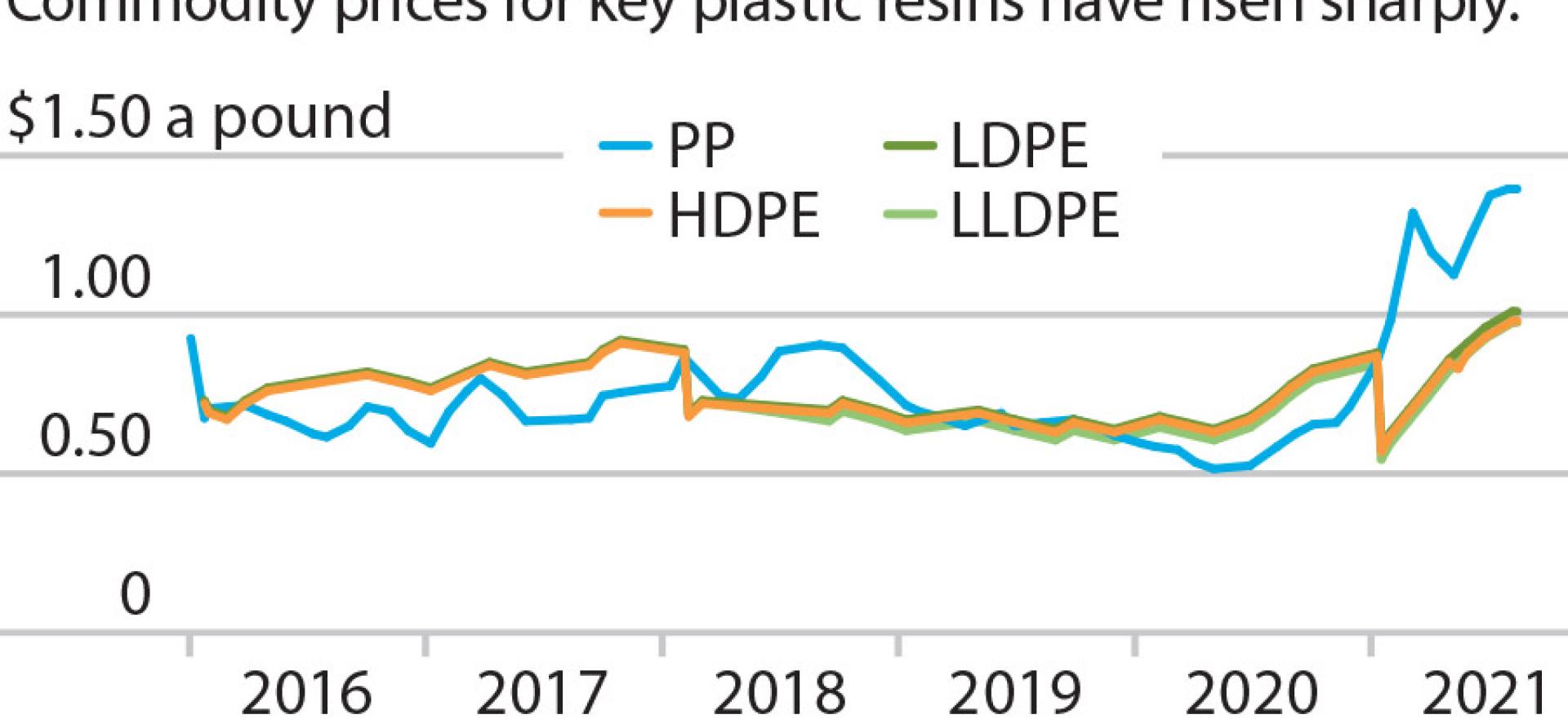

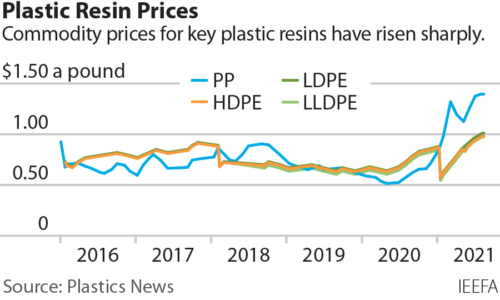

We need to start with some facts. The industry is telling us that the tax will cause lost jobs and production cuts. Plastics producers report that profits are “fantastic.” Most basic plastics like polypropylene and high-density polyethylene have seen extraordinary price increases through 2020 and have continued to skyrocket this year.

The price of polypropylene is hovering around $1.35 per pound, up from 55 cents in early 2020. Most other basic plastics have increased from 50 cents per pound to more than $1.00 per pound.

Prices are way above where they should be. Even if they drop a little, the high prices will still place a burden on the cost of vital goods to the public.

Plastics producers blame the price mayhem on the coronavirus pandemic and severe weather along the Gulf Coast. But IEEFA’s research shows that the plastics industry rebounded swiftly from both challenges.

The use of plastics runs through almost every facet of life

Plastics Exchange, an industry trade paper, reported on Aug. 13, 2021, that “producers have reported fantastic financial results” (See para. 8, from pull-down menu for Aug. 13, 2021 report). Most of the major companies reported solid profits in the second quarter of 2021. ExxonMobil, an industry leader, saw its petrochemical profits soar, even as its drilling and refining operations continued to flounder.

There are bigger problems. The industry is run by a handful of companies. In the largest polymer groups, a handful of companies control more than 70% of the market. ExxonMobil, Dow, Braskem, Formosa, LyondellBasell Industries and Chevron set the market. The same companies that make the polymers control the ethylene market, the feedstock for the plastic resins. Market price-setting lacks any sense of transparency, and no one watches or regulates the critical financial metrics that govern the industry.

During the pandemic, the industry lobbied and appropriately received designation as an essential part of the economy. The use of plastics runs through almost every facet of life, underscored during the pandemic by its work to supply personal protective equipment. That part of the industry did well during the pandemic, while harder plastics used in cars and construction took a substantial hit.

It’s apparent to all that we need to use less plastic, but there is no venue for deciding what plastic is needed. It’s also apparent that plastic production needs to pollute less and contribute to climate solutions, not continued degradation. Finally, it’s apparent the plastics industry is a protected political class that can pass along costs without consequence. This is dysfunctional.

A comprehensive regulatory system is required

The recent inclusion by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of plastic on its list of essential economic sectors has changed the way the industry should be viewed. Regulatory oversight of the industry is uneven in scope and uncoordinated in implementation and enforcement at a time when the sector has become more important.

The questions of price, profit and taxation play out against a backdrop of an industry that produces, markets and sells its products without regard for issues such as the use of plastics for life-saving needs, manufacturing locations and processes, and the risks that come with it. A comprehensive regulatory system is required to answer questions: What plastics are needed? Where should production be located? How much should be charged, and what are fair prices and profits? How should capital be allocated, and what governmental supports are proper to address need, as well as health, environmental and climate considerations?

Until those questions are answered, we will continue to have legal and political battles that seek to influence an economic process with dire implications for both the health and safety of the public and the planet.

Tom Sanzillo ([email protected]) is IEEFA’s director of financial analysis.

Suzanne Mattei ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy policy analyst.

Related items:

IEEFA. Army Corps of Engineers requires full environmental review for Formosa petrochemical project in Louisiana, August 2021.

IEEFA. CMD’s bag initiative raises questions for future of oil, gas and plastics industries, May 2021.

IEEFA. Shell’s Pennsylvania Petrochemical Complex: Financial Risks and a Weak Outlook, June 2020.