IEEFA U.S.: Frackers gained in 2021 as sweet spot of rising oil prices and lower costs boosted profits

For the first time since the dawn of the fracking boom, North America’s oil and gas companies generated a generous surplus of cash in 2021. The bonanza stemmed in part from high oil and gas prices. A cross-section of 28 North American shale-focused oil and gas producers generated almost $40 billion in revenues during the first three quarters of the year, the highest level since 2014.

Three converging trends are poised to send the oil industry’s capital spending higher in 2022

Just as importantly, North America’s oil and gas industry kept spending in check. The same companies collectively spent $21.7 billion on well drilling, well completions (fracks), and other capital expenses in the first three quarters of 2021. That was about 8 percent lower than the same period in 2020, and 43 percent lower than 2019, the last full year before the COVID-19 pandemic.

For years, investors had urged oil and gas companies to spend less money on new wells, and instead use their cash flows to pay down debt and pay out dividends. In 2021, the industry finally heeded that advice.

However, three converging trends are poised to send the oil industry’s capital spending higher in 2022.

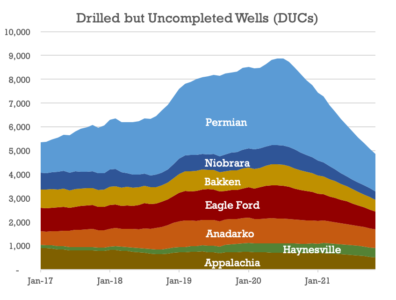

The first trend is the depletion of the industry’s inventory of drilled but uncompleted wells, or DUCs. In the years leading up to the pandemic, fracking companies drilled more wells than they completed. But as global oil prices collapsed in 2020, the industry reversed course, completing more wells than it drilled. As a result, the oil and gas industry rapidly depleted the massive DUC inventory it had built up over the preceding years. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) in seven shale basins.

Using DUCs allowed the industry to cut spending on drilling, which accounts for 25% to 35% of the cost of a new well. In seven key basins tracked by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), domestic producers relied on DUCs for a little more than 1,000 newly completed wells in 2020, and about 2,900 in 2021, saving as much as $10 billion in drilling expenditures over two years.

However, these savings are unlikely to last. The DUC inventory has now reached its lowest level since 2014. There is only so low it can go; the industry must always keep some DUCs on hand to schedule their completions efficiently. If fracking-focused companies want to maintain current levels of production, they may soon have little choice but to increase the pace of drilling. That will mean more drilling rigs in operation, and more spending to keep them running.

These savings are unlikely to last

DUC inventories vary by region. The Permian Basin, which hosts about half the drilling activity in the U.S. and is also the largest oil-producing region, has slightly less than four months of DUC inventory, or about half its five-year average. In contrast, the Haynesville’s current DUC inventory of seven months is in line with the region’s five-year average. We would expect some regions to respond to the shrinking DUC inventories sooner than others.

A second trend that is likely to boost capital spending is inflation. Preliminary data shows that drilling costs (or, more specifically, the Producer Price Index for Drilling Oil and Gas Wells – Primary Services as tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics) have risen 7% since January. Even if costs remain flat for the coming year, the industry will still face higher capital expenses in 2022 than the 2021 average.

Oilfield service costs tend to keep pace with oil and gas prices, so a rapid decline in oil and gas prices could ease price pressures. Yet falling prices would also crimp revenues, hurting the industry’s bottom line.

A THIRD TREND THAT MAY BOOST CAPITAL COSTS IN 2022 is the gradual increase in the pace of well completions. According to the EIA, the industry completed an average of 772 wells per month in the first half of 2021, but the figure increased to 868 wells per month from July through November. As production gradually rebounds, the industry will face higher total costs for bringing new wells into production, further boosting capital spending.

The first two factors—the exhaustion of DUC inventories and inflation—could boost next year’s capital costs by 10% (i.e., 8% from normalized drilling pace and 2% from inflation pressures), without any change in the number of wells completed. Costs will rise still higher if the industry continues to complete more wells. If oil and gas prices fall next year, as futures markets now predict, the oil and gas industry will be pinched between rising costs and falling revenues, jeopardizing its ability to generate cash in the new year.

The 2021 year was atypical for the oil and gas industry. Producers trimmed capital costs, even as prices for oil and natural gas rose to their highest level in years. But 2022 could see the opposite, with costs rising and energy prices moderating. This pendulum swing could prove quite costly for producers in the coming year.

Trey Cowan ([email protected]) is an IEEFA oil and gas industry analyst.

Clark Williams-Derry ([email protected]) is an IEEFA energy finance analyst.

Related items:

IEEFA. Has the Bakken Peaked?

IEEFA. ExxonMobil: Permian Leader or Just Another Fracker?

IEEFA. Deep in the Heart of Texas, Oil and Gas Losing Economic Luster