West Virginia effort to save Pleasants coal plant collides with economic reality

Key Findings

State regulators effectively approved a $3 million monthly rate increase for as much as 12 months as two of the state's utilities consider purchasing the aging Pleasants plant.

The order would charge consumers at least $3 million a month for as long as a year just to look into buying the plant—a 2.3% increase for most bills.

The legislature’s poorly planned effort to save a single coal plant could do broad and long-lasting economic damage in West Virginia as costs to taxpayers and ratepayers increase, potentially without even saving the plant.

Rather than trying to find the lowest-cost power solution, the PSC is asking consumers to subsidize a study on the purchase of Pleasants that currently offers zero benefits to them.

West Virginia's unbending support for the coal-fired Pleasants Power Station is about to cost ratepayers again.

State regulators this week effectively approved a $3 million monthly rate increase for up to 12 months, requested by two of the state's regulated utilities as they continue to consider purchasing the 43-year-old plant—one they didn’t seek to buy, don’t need, and that could sit idle the entire time. The study’s cost works out to a 2.3% rate increase for most customers.

Pleasants is currently owned by Energy Transition and Environmental Management (ETEM), a site cleanup company, and leased and operated by an unregulated power company, Energy Harbor—which recently sold the plant to ETEM for demolition after May, when they planned to shut it down. Neither ETEM nor Energy Harbor receive any ratepayer support, since the plant’s electricity is sold into the competitive PJM power market and not distributed directly to consumers.

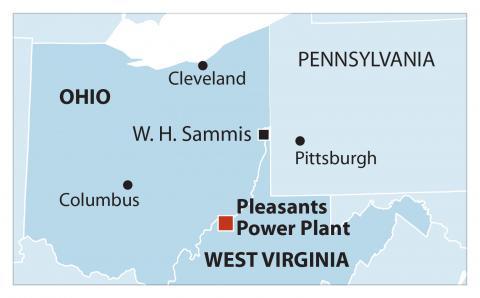

The latest effort to save the plant picked up momentum in February, when the West Virginia House of Representatives passed a resolution that “strongly encourages” one of the state's regulated power companies, Monongahela Power, to purchase the Pleasants plant. The legislature sent a copy of the resolution to both Monongahela Power and the West Virginia Public Service Commission, which oversees the utility. Monongahela Power and Potomac Edison, which together serve the northern two-thirds of West Virginia, were asked by the PSC to look into purchasing the plant; both are subsidiaries of Ohio-based FirstEnergy. The added charges they are requesting would not apply in the state capital and the rest of the southern part of the state, which is served by a different utility.

For their increased bills, the utilities’ customers appear unlikely to get much. Even with the $3 million monthly charge, “not one ton of coal would be burned, not one kilowatt-hour of generation will be coming out of that plant,” as the utilities study a purchase, according to testimony from Robert Williams, director of the PSC’s Consumer Advocate Division, at an April 21 hearing. Because of the complete lack of benefits for customers, the rate hike is likely to face legal challenges.

The 1,300-megawatt (MW) facility, a money-losing plant that has been on the edge of closure for years, was first slated to be shut down in 2019, but was saved at the time by a $12.5 million annual tax break passed by the legislature. As with the earlier deal, the current effort flies in the face of basic economics.

A FirstEnergy executive, David Pinter, who also testified at the April 21 PSC hearing, said that coal-fired plants such as Pleasants “do not make money in the current markets as a general rule.” Quite simply, the plant is uncompetitive in the PJM power market because it does not generate electricity as cheaply as other plants in the region.

For the state’s coal industry, saving Pleasants would largely be a symbolic victory. The plant would not use coal during the study period and may only be able to run for a few more years due to pollution control deficiencies. FirstEnergy also has already said that it would almost certainly shut down its Fort Martin plant if it were to purchase Pleasants. The companies could choose to run the plant very little, as many utilities currently do with their coal plants when cheaper sources of power are available.

It is difficult to overstate the unusualness of the Pleasants deal. Most regulated utilities around the country submit detailed, long-term plans every few years about building or retiring power plants to meet their electricity demand, frequently with multiple scenarios and detailed cost information about achieving those goals. The plans must be reviewed and approved by the state public service commissions that regulate them. Additionally, some types of corporate transactions by electric companies or aspects involving interstate transmission and wholesale electricity may require approval by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Likewise, changes to electricity rates usually go through long-established review and approval processes. In return for this oversight, power companies get a monopoly on selling electricity to customers in a particular area and a guaranteed return on their financial investments; states are able to ensure reliable electricity delivery and universal access at reasonable rates to residents.

In this case, though, Monongahela Power and Potomac Edison were not looking to purchase Pleasants. Instead, they were first asked by the PSC to look into buying it and file a report by March 31. Meanwhile, Energy Harbor—itself a former FirstEnergy subsidiary that only emerged as an independent company in 2020 after going through bankruptcy—decided it was going to close the plant in May. As part of that process, it sold the plant on Dec. 28, 2022, to ETEM, with an arrangement to lease it back and operate it until it closed. Now, FirstEnergy is scrambling to negotiate agreements with these companies to retain experienced workers and keep Pleasants in an operational condition while it conducts a detailed technical and financial analysis of what it would cost to take over and run the plant.

Even if those near-term agreements can be put in place, FirstEnergy will ultimately need to tell the PSC if a purchase is feasible, and how much it might cost ratepayers to buy and run the plant if purchased.

Monongahela Power and Potomac Edison own two other large coal plants in West Virginia, Fort Martin (1,098 MW) and Harrison (1,984 MW), and have already said that owning three coal plants “doesn’t make sense.” Instead, they are tentatively suggesting that the most viable path might be to shut down Fort Martin, and save as much as $50 million that would no longer be needed to build pollution controls there.

It is understandable that West Virginia is seeking to preserve the local and statewide economic benefits that Pleasants has provided. But at what cost?

- If the Fort Martin plant, just 100 miles to the northeast, were closed as a result of purchasing Pleasants, it would eliminate jobs, cut coal demand, and otherwise hurt the economy around Morgantown, W.Va.

- Big industrial customers in the state are protesting that the higher electric rates, on top of big increases over the past year, might require them to cut jobs and spending.

- The owners of Longview Power, another unregulated coal plant (710 MW) next to Fort Martin that is just 11 years old and more efficient than Pleasants, have asked the PSC why it isn’t being considered for purchase, highlighting the arbitrariness of the current process and its failure to look more broadly at lowest-cost solutions.

- West Virginia’s gas industry, which made the state the fifth-biggest producer in the country last year, and a big supplier of the fuel to power plants in the region, must be wondering why the state is trying so hard to help coal, a key competitor.

In short, the state’s poorly planned effort to save a single coal plant could do much broader and longer-lasting economic harm in West Virginia as costs to taxpayers and ratepayers increase.

Taking its cue from the legislature, the PSC’s order is adding to the damage by turning the regulatory process on its head. Rather than trying to find the lowest-cost power solution that would protect ratepayers from higher bills, the PSC is demanding electric customers subsidize a study on the purchase of Pleasants that would provide no benefits to them for as long as a year, and could easily lead to higher rates for years to come.