Stepping stones for a broader carbon tax scheme in Bangladesh

Key Findings

A carbon tax is a more appropriate instrument for Bangladesh than an emissions trading scheme because of the ease of implementation. A tax can also provide a clear price signal, while the carbon revenue can be a good funding source for clean energy projects.

At the outset, the government should fix goals that a carbon tax can help it accomplish. These goals may include reducing GHG emissions, improving air quality and promoting renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Early stakeholder engagements can help in a positive response to the implementation of a national carbon pricing tool. Subsequently, the government can select the agency to implement the carbon tax scheme and monitor the system.

Growing concerns over climate change have led to countries incorporating carbon pricing instruments in their energy and climate policies to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and achieve environmental goals. Emissions trading scheme (ETS) and carbon tax are the two major carbon pricing instruments worldwide. While trading of emissions between polluting entities sets the price of carbon in an ETS, a carbon tax is a charge per unit of emission fixed by a government. As of 1 April 2023, ETS and carbon tax together covered around 23% of global GHG emissions.

Notably, Bangladesh’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) require it to amplify efforts to unconditionally reduce 3.39 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the transport sector by 2030. Therefore, the government’s recent decision to levy an environmental surcharge, similar to a carbon tax, on multiple cars appears to be a good move to restrict the number of vehicles with internal combustion engines (ICE). This surcharge also applies to electric cars, which may affect demand for the same, in effect penalising the cleaner alternative.

While Bangladesh is a small GHG-emitting nation, it often confronts the challenges of containing pollution. A broader carbon tax scheme could help overcome the challenges of unconditionally containing 6.73% of GHG emissions from the selected sectors by 2030.

Although carbon tax is a seemingly easy tool to deploy, Bangladesh should pursue a systematic approach if it wants to push ahead with the tool for achieving its future broader climate and environmental policy goals.

Carbon tax is suitable for Bangladesh

Previous studies show that a carbon tax is a more appropriate instrument for Bangladesh than ETS because of the ease of implementation of the former. Moreover, a tax can provide a clear price signal, while the carbon revenue can be a good funding source to support clean energy projects in Bangladesh amid its low tax-to-GDP ratio.

The presence of small units of GHG emissions in Bangladesh makes ETS a difficult instrument to apply.

The environmental surcharge on multiple cars comparable to a carbon tax

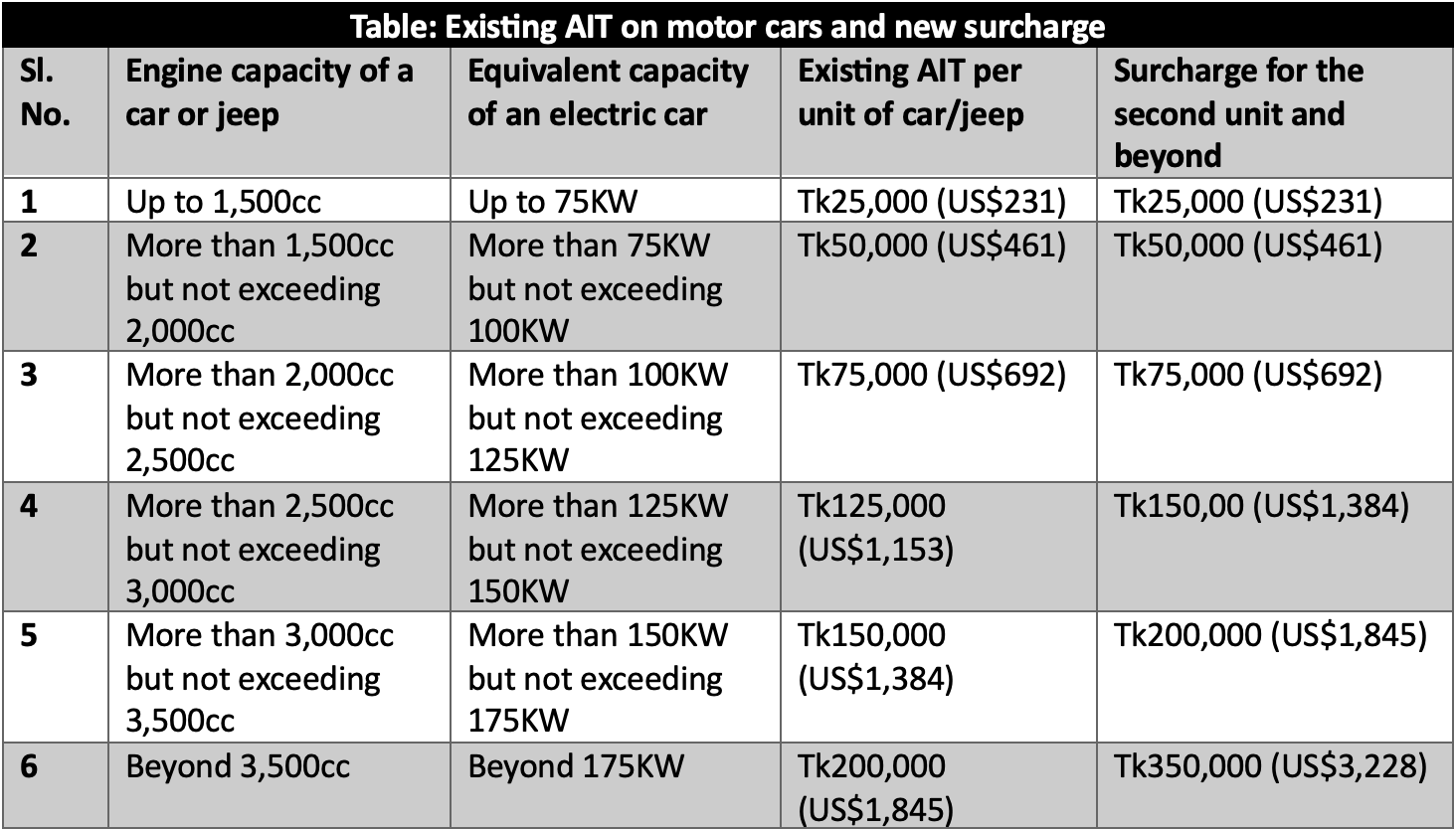

The existing rule stipulates that a person must pay an advance income tax (AIT) for each car they own. This AIT ranges from Bangladeshi Taka (Tk) 25,000 to 200,000 (US$232 to US$1,852) per vehicle depending on the size of the engine in cubic centimetres (cc) or equivalent kilowatt (KW) (see table below).

The number of cars is rising rapidly, choking roads and polluting the environment. To curb the growth, the finance ministry of Bangladesh laid out a surcharge (similar to a carbon tax) structure for the second and additional cars in the budget proposal for the financial year (FY) 2023-24, which is subsequently approved by the government. This surcharge applies to both electric and conventional ICE-based cars.

An individual will need to pay a surcharge on top of the existing AIT for the second car. A second car of 1,500cc or 75KW capacity will lead combined AIT and surcharge to reach Tk50,000 (US$462) (see table below).

Source: BRTA, 2020; The Daily Star, 2023; cc to KW conversion factor: 1KW=20cc

While the surcharge penalises owning a second car, it poses some questions. A family can still own several ICE cars in the name of different family members, negating the objective of reducing cars and avoiding the payment of a surcharge.

Also, since most car owners currently have ICE cars, they may consider buying an electric car as their second unit. However, the surcharge may change their decisions. The government may consider waiving the surcharge for a certain time, say one year, for those buying a second car to switch to an electric car from the existing ICE.

With Bangladesh aiming for 30% electric vehicles (EVs) by 2030, the new surcharge will hurt the growth of EV sales. Instead, the government should design conducive policy measures to incentivise a rapid penetration of EVs, such as using the surcharge mop-up from ICE cars for building EV charging infrastructure.

Yet, the surcharge for multiple car ownership can provide Bangladesh with the experience of a small pilot if the country plans for a broader carbon tax in the foreseeable future.

Framework for a broader carbon tax scheme

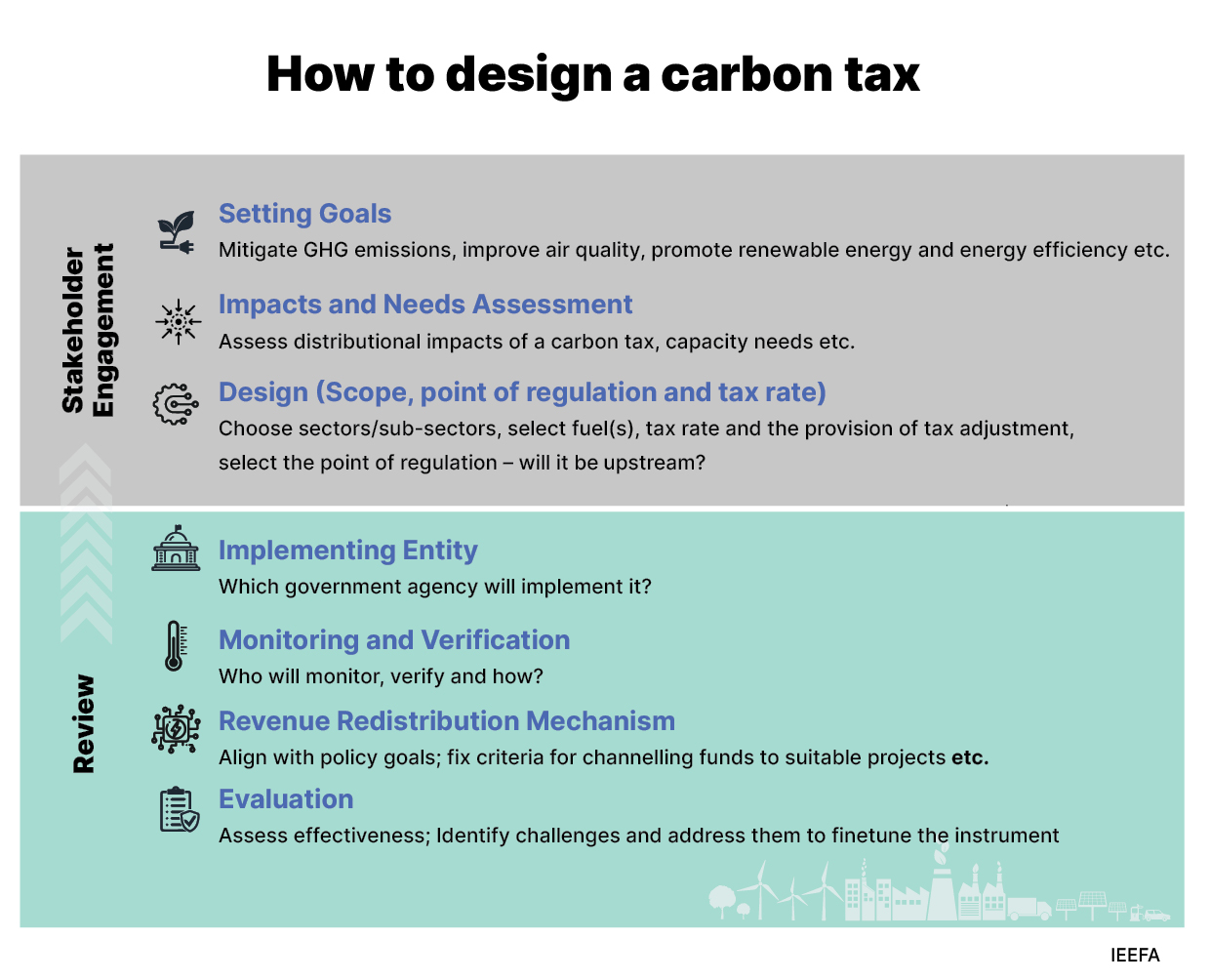

While the recently approved surcharge on multiple cars may be an important move, Bangladesh should carefully design and implement an impactful instrument on a larger scale in the future (see below schematic).

At the outset, the government should fix goals that a carbon tax can help it accomplish. These goals may include reducing GHG emissions, improving air quality and promoting renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Source: Adapted and modified from the author’s own study (Ecologic Institute, 2019)

Once the government sets the goals, it should conduct an impact and needs assessment. This is because a carbon tax on a sector/sub-sector or particular fuel will make products and services costlier, with distributional impacts on people of different quarters. The impact assessment will help determine the government support required for people of lower income strata. Similarly, the needs assessment will detail the capacity development measures necessary to implement a sector- or fuel-wise carbon tax in Bangladesh.

It is then necessary to explore the design features of the instrument, involving the identification of the sectors or sub-sectors of the economy and/or fossil fuel for inclusion. Subsequently, the discussion starts with the tax rate, which should ideally be low initially.

During these three steps, extensive stakeholder involvement will make people aware of the goals, design elements and measures that the government planned to address negative impacts, particularly on the poor. Early stakeholder engagements help in a positive response to the implementation of a national carbon pricing tool.

Subsequently, the government shall select the agency to implement the carbon tax scheme and monitor the system.

However, revenue redistribution or recycling to the economy is a key step to the success of a carbon tax. As such, the government should set the purpose of the revenue collected through a carbon tax. The government may channel carbon revenue to incentivise renewable energy, which is developing in the country, albeit slowly. Alongside this, the government may run a dedicated support program for the people impacted by higher prices attributable to the carbon tax. This will help achieve environmental goals while addressing the distributional impacts on the poor.

Finally, an evaluation mechanism will help assess the instrument's effectiveness during its initial period of operation and finetune it if necessary.

While Bangladesh has low per capita GHG emissions, the implementation of a carbon tax on a broader scale could still help the country achieve its NDC goals. Bangladesh should stick to a systematic approach to protect people exposed to higher prices of products, channel carbon revenue to the preferred sectors/sub-sectors and ensure the instrument's effectiveness. The environmental surcharge levied on multiple cars could help draw some lessons for a future national or sectoral carbon tax scheme.

This article was first published in the Energy & Power Magazine.